America Cannot Kill Its Way Out of the ISIS War

This is not a simple "we win, they lose" scenario.

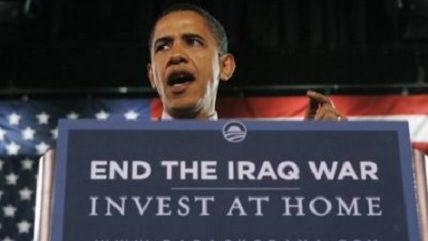

The U.S. is a long way from resolving "Operation Inherent Resolve", our new and undeclared war in Iraq and Syria. President Barack Obama says it's "going to be a long-term campaign. There are not quick fixes involved. … As with any military effort, there will be days of progress and there are going to be periods of setback." We're only four months into what the president suggests could be a three-year fight to "degrade and destroy" the Islamic State (ISIS).

The looming question is, how does war with a totalitarian jihadist group actually end successfully, rather than morph from one military campaign into another ad infinitum? It's going to take more than just bullets and bombs. And it's not going to be a simple "we win, they lose" scenario.

ISIS does have weak points militarily. If allied forces can free cities like Mosul or Kobane, they'll strike a serious morale blow that could dissuade future recruits. America is also already bombing oil refineries, a major revenue stream, and there's a good chance ISIS doesn't use banks, so they have millions, if not billions, in cash that's vulnerable for targeting.

Whether the American-led coalition can actually pull off a military victory is yet to be seen. But our airstrikes aren't as effective as hoped, the majority of American troops want nothing to do with this war, our humanitarian aid and weapons have fallen into ISIS's hands, and our relatively small coalition is divided by rivalries and historical tensions.

"The kinetic part of this—drone strikes, airstrikes, Special Forces raids—that is just a tactical and operational tool to constrict the threat group's mobility," explains Sebastian Gorka, Major General Horner Chair at the Marine Corps University and Adjunct Professor at the Institute on World Politics.

A military success, however, does not guarantee the prevention of bigger, badder groups in the future. After all, we battled back Al Qaeda and now have ISIS, its ugliest off-shoot, on our hands. According to a 2008 Rand Corporation study, when terrorist groups do actually cease to exist, "nearly 50 percent of the time [since 1968], groups ended by negotiating a settlement with the government; 25 percent of the time, they achieved victory; and 19 percent of the time, military forces defeated them." And, "big groups of more than 10,000 members have been victorious more than 25 percent of the time."

Christopher Harmon of the Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies has also looked at historical trends, and his "How Terrorist Groups End" lays out five potential courses: the use of force, which the U.S. has been hesitant to commit in the current case; a good grand strategy, which requires even greater commitment; decapitation of leadership, which is "exceedingly difficult to do"; the terrorist group entering the political process in the occupied nations; or the group winning state power.

So, is it possible to speak diplomatically with an organization that has a stated goal of establishing a religious totalitarian state stretching from the western coast of Spain deep into central Asia?

ISIS is not a rag-tag outfit composed solely of crazies. It's a well-organized, mafia-esque, and business-savvy enterprise. In command are some of the high-ranking Sunni members of the Saddam Hussein regime. Many were driven there by the corrupt, post-war, American-approved Maliki administration, which ousted highly-skilled Sunnis from Iraq's military and instituted "unabashedly Shiite-first policies." Barely half of Sunnis had faith in their government even a year before ISIS showed up.

"Let's get really Machiavellian," says Edward Turzanski of the Foreign Policy Research Center. "And let's say they're less interested in some sort of Islamist ideal than they are in carving out their own sphere of influence" and "protecting Sunni Arabs in Iraq." This could come in the form of Harmon's fifth option, which has previously occurred fully in the case of Bolshevik Russia and, to lesser degrees, with Hamas in Palestine and Hezbollah in Lebanon. Or it could resemble Harmon's fourth scenario, as with the Irish Republican Army (IRA), which abandoned terrorist activity and now has former militants in office.

"As a matter of historical fact, insurgencies end by negotiations," says Christopher Preble of the Cato Institute. So who would be equipped to conduct such talks?

Although the U.S. is the head of the current anti-ISIS coalition, it would be a domestic political impossibility for America to take the lead in negotiations. Our mythos is that America wins wars cleanly without concessions, and President Barack Obama is personally unlikely to backtrack on his absolutist rhetoric about defeating ISIS without talks.

ISIS is "challenging the authority of established sovereign states," and as such, "any negotiations should be between the [Iraqi, Syrian, and Kurdish regional] governments and the insurgents," says Preble. Turkey may also be in a willing position to participate in negotiations, since it has already made trade-offs with ISIS and the group is now at Turkey's border.

It's possible, however, that talks couldn't be conducted at all. Some analysts contend that the West should not overlook the seriousness of ISIS's commitment to fighting tooth and nail for a caliphate. Harmon believes that diplomacy would be very difficult.

Gorka, citing ISIS's immense brutality and conviction that this is "the final war before the judgment day," says it would be impossible to get them to compromise. But he also notes that "we cannot kill our way out of this war" or we'll be at it for centuries. Rather, America's battle with ISIS, or in "any war against a totalitarian organization … will only come when you have adequately undermined and delegitimized the ideology of the organization. You have to destroy the brand."

Gorka suggests that the U.S. needs an analog to Reagan's Berlin Wall speech, in which the president shamed the communists, "blew their credibility," and made them "uncool."

The State Department is trying something of that sort with a social media campaign called "Look Again, Turn Away." It sends the right messages: ISIS primarily targets other Muslims, its fighters are deserters, and they do not really practice Islam or have real authority over Islamic beliefs.

But, again, the U.S. may not be the best equipped to handle this front. Scott Stewart, vice president of tactical analysis at the global intelligence firmStratfor, says, "America is seen as an outsider and a crusader. It really doesn't have any entre into that battlefield. Quite frankly, the stuff the State Department is doing is almost goofy."

One of ISIS's greatest strengths is its social media propaganda campaign, which makes the organization appear fearsome and enticing, whereas the State Department's work looks poorly Photoshopped. Best suited to break ISIS's grip on ideas, suggests Stewart, will be prestigious religious authorities at Saudi Arabia's Council of Senior Scholars and Egypt's Al Azhar University. "This is a battle for the soul of Islam, it's something that has to be battled between Muslims themselves," Stewart says.

None of these are short-term or singularly effective strategies—it's much harder to end a war than to start one. But they are important strategies that the American-led coalition must consider if the threat of totalitarian Jihadism is to be eliminated and the U.S. is to actually end its long counter-terror campaigns in the Middle East.

Show Comments (109)