New Company Practices Virtual Eugenics

GenePeeks aids parents in their quest for healthier babies by reducing the odds of structural or genetic birth defects.

Childbearing is a lottery. The good news is that most babies are winners who are born without major structural or genetic birth defects. But wouldn't it be good to stack the odds further in favor of having a healthy baby?

That's the aim of the new genetic testing company GenePeeks. Co-founded by the Princeton geneticist Lee Silver and the Harvard Business School professor Anne Morriss, GenePeeks and its Matchright service pair women wanting to use donated sperm with donors whose genes, when combined with theirs, are more likely to produce a healthy child.

Morriss has a particular personal interest in the technology. Morriss and her wife Frances Frei decided six years ago to have a child using the services of a reputable sperm bank. They pored over the profiles of potential donors and selected one; nine months later, Morriss gave birth to their son Alec. A routine infant screening test found that Alec had been born with a rare (1 in 17,000) genetic disorder, medium chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (MCAD) deficiency, that blocks him from converting certain fats into energy. To prevent seizures and sudden death, he would need to be fed every few hours.

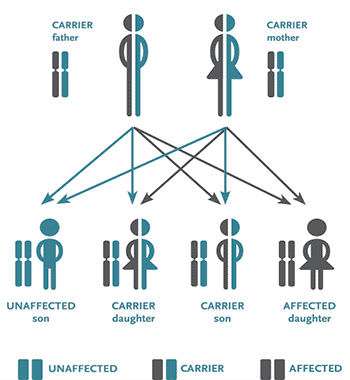

No one in Morriss' family had ever suffered from the disorder, but she was a carrier of the recessive gene that only manifests the disease when it is inherited from both parents. Unluckily, the sperm donor she chose was also a carrier. GenePeeks would have steered Morriss away from him.

No individual's genome is free of all potentially harmful genetic variants. Indeed, researchers estimate that every person carries about 400 damaging genetic variants. (For example, my genotype test at 23andMe reports that I have a recessive allele for Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency. People born with two Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency alleles are at greater risk of lung and liver disease.) So GenePeeks has partnered with two sperm banks, one in New York and another in Seattle. (They hope to work with more sources in the future.) Donors at both banks have been screened for specific recessive genes related to various disorders. GenePeeks also tests each client seeking donated sperm for the same recessive variants.

The company takes those results and, using algorithms devised by Silver, simulates the fertilization process by digitally combining the client's and donors' test results to generate the genomes of thousands of virtual children. The system then gauges the likelihood that the genetic combinations would produce disease. Donor matches that yield a higher risk of complications are screened out. The client is then offered a customized catalog of donors whose genetic variants—when combined with the client's—are less likely to produce the genetic disorders included in the company's test panel.

New York State strictly regulates the types of diagnostic information that test laboratories provide to clients. To avoid regulatory hassles, GenePeeks does not provide its clients with any information about the specific conditions associated with any particular pairing. Instead, if a pairing exceeds a predetermined threshold for genetic risk, the donor is simply removed from the client's consideration. Typically, the results from Matchright pairings will exclude about 20 percent of the current donors from an individual client's catalog.

Right now the company has 162 gene-screened donors available. The client tests are done by an outside laboratory, and the company promises a 4-week turnaround time. The Matchright service costs $1,995, on top of the other charges associated with artificial insemination.

Will Matchright genetic screening ever be applied to egg donors as well? "That day may be very soon," Silver says. "We are in negotiations with an egg bank right now."

The Matchright process reduces genetic risk, but it cannot guarantee that a client won't give birth to a sick baby. While the company tests for about 500 recessive disease variants, it does not test for the thousands of different rare genetic variants that researchers believe are associated with various disorders. In addition, the company is not currently testing for disorders linked to X chromosomes, which are more frequently expressed in men since they inherit only one X chromosome from their mothers. And its tests cannot detect chromosomal abnormalities that occur after fertilization, such as those that result in children being born, for example, with Down Syndrome.

That being said, the Matchright process can easily include and evaluate new information about genetic disease risks as it becomes available and eventually even scale up to analyze complex conditions in which multiple genes play a part.

Naturally the new technology has provoked objections. In a New Scientist article, Marcy Darnovsky, executive director of the Berkeley-based Center for Genetics and Society, warned that "we could find ourselves with new inequalities that are written into the genome." It's hard to see how increasing the chances that babies are born healthy will somehow result in the proliferation of invidious social inequalities.

"I think about it in simple terms," Morriss told The Boston Globe last year. "If we can reduce the number of kids that have to get these diseases, then we should." Or at least not stand in the way of prospective parents who want to use this technology to increase the odds that their kids will be born healthy.

Show Comments (272)