Today at SCOTUS: Prison Security vs. Inmates' Religious Liberty

The U.S. Supreme Court will hear oral argument today in the case of Holt v. Hobbs. At issue is the Arkansas Department of Corrections' refusal to allow a Muslim inmate named Gregory Houston Holt (also known as Abdul Maalik Muhammed) to grow a one-half inch beard in accordance with his religious beliefs. According to state officials, the no-beard policy is essential to maintaining safety and security. It prevents inmates from hiding contraband on their persons, those officials claim, and also prevents inmates from changing their appearance by shaving.

But the mere assertion of such rationales is not sufficient by itself to justify this restriction. In order to pass muster, the prison's no-beard policy must satisfy the terms of a federal law known as the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act (RLUIPA), which holds: "No government shall impose a substantial burden on the religious exercise" of prisoners residing in institutions that receive federal funding, unless the government can demonstrate that the burden furthers "a compelling government interest" and "is the least restrictive means" of doing so. If that language sounds familiar, it's because the RLUIPA largely borrowed it from the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, the federal law recently invoked by the Supreme Court in the Obamacare case Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores Inc.

In this case, the law is squarely on Holt's side. As his lawyers at the Becket Fund for Religious Liberty observe in their main brief, "forty-four other state and federal prisons with the same security interests allow the beards that Arkansas forbids." In other words, while prison security is undoubtedly a "compelling government interest," the no-beard policy is far from the "least restrictive means" of achieving it.

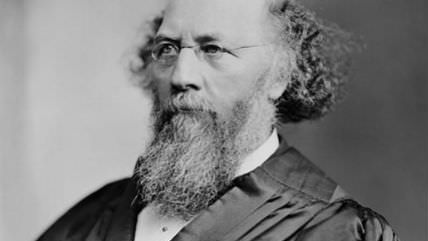

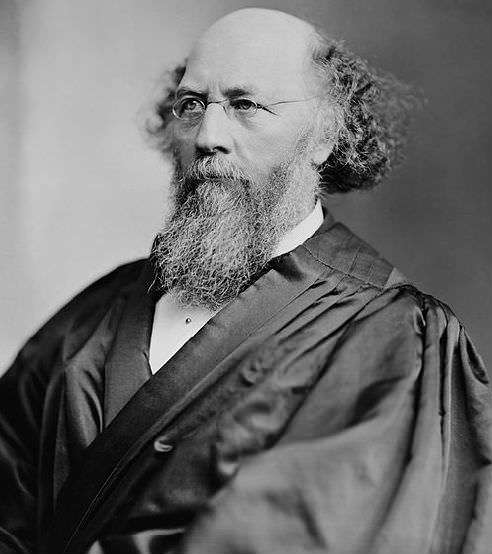

For its part, Arkansas maintains that its correctional officers are entitled to broad deference from the courts. But that argument not only fails to satisfy the strict requirements of the RLUIPA, it also runs counter to an important 19th century precedent set by Justice Stephen Field, one of the Supreme Court's first great conservative jurists. In the 1879 Circuit Court case of Ah Kow v. Nunan, Justice Field confronted a San Francisco ordinance which required all male prisoners in the county jail to have their hair "cut or clipped to an uniform length of one inch from the scalp." City officials claimed it was a public health regulation, but in fact the law's real purpose was to humiliate male Chinese immigrants, who commonly wore their hair in long braided ponytails known as a queues. This "queue ordinance" (as it was known throughout the city) was just one of the many racist and xenophobic regulations passed by California officials in response to the arrival of Chinese immigrants.

Field struck it from the books. To describe the "hostile and spiteful" queue ordinance as a valid health measure "is notoriously a mere pretense," he declared. "The ordinance acts with special severity upon Chinese prisoners, inflicting upon them suffering altogether disproportionate to what would be endured by other prisoners if enforced against them."

Field's logic holds equal force in the present case. A prison regulation which harms religious minorities in a manner that is "altogether disproportionate to what would be endured by other prisoners" deserves no deference from the Supreme Court.

Show Comments (21)