How Not to Legalize a Drug

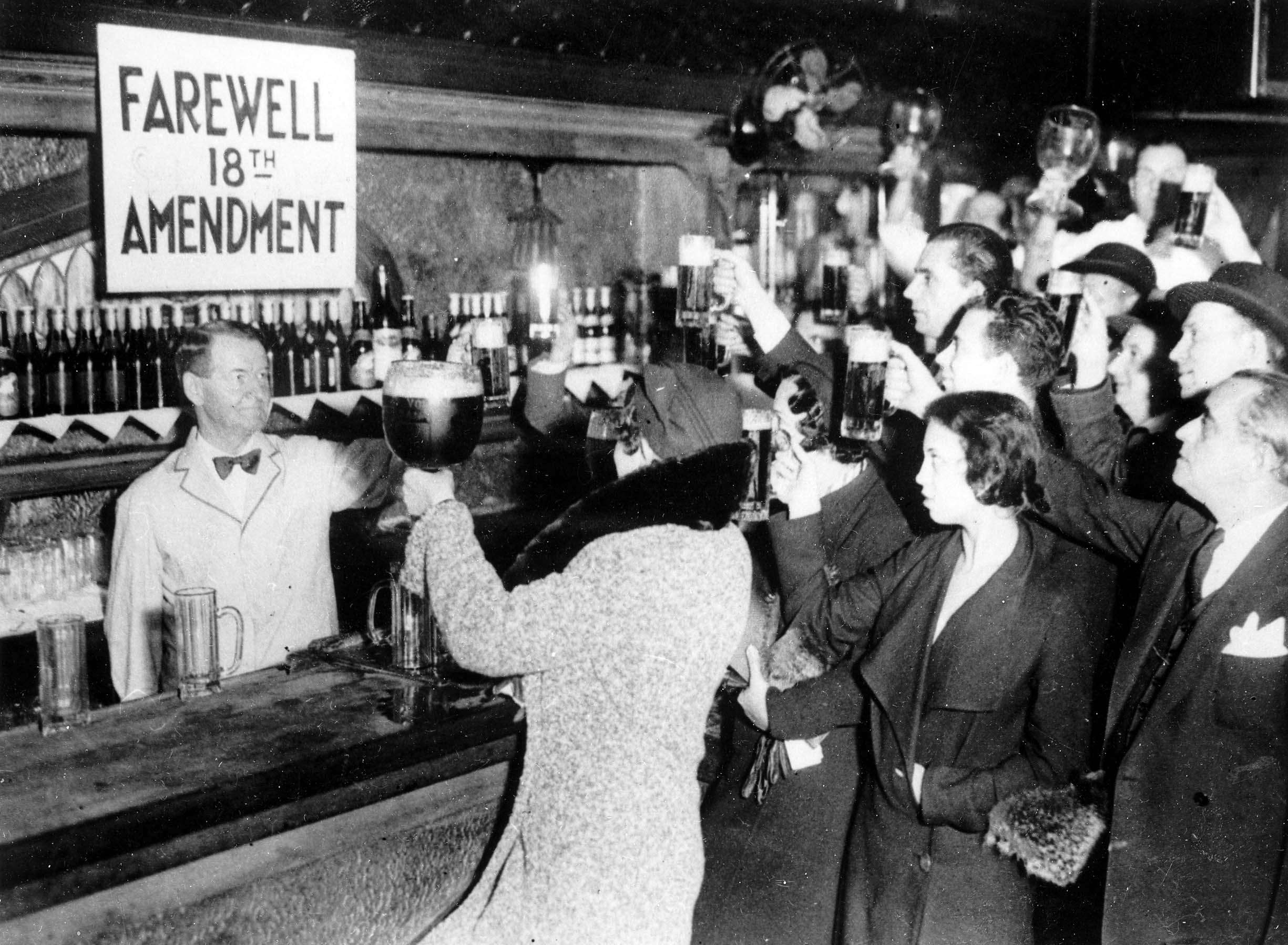

Yanking alcohol back out of the black market left America with a wicked Prohibition hangover.

By the time Franklin Delano Roosevelt was elected president of the United States in 1932, the Great Depression had been underway for three years—and Prohibition had gone on for what the literary critic and crank H.L. Mencken quite accurately described as nearly "Thirteen Awful Years." A quarter of the American workforce was unemployed. FDR had run on Repeal, proposing a win-win solution: The federal government would allow states to reopen the breweries and distilleries to create much-needed jobs, then heavily tax the alcohol to pay for what would become the New Deal.

Prohibition, which started as a "noble experiment" in 1920, ended up rolling out the red carpet for organized crime. Violence wracked cities as criminal syndicates fought over territory while the police force, politicians, and Prohibition Bureau agents were bribed to look the other way. Citizens widely disregarded the law of the land, and even congressmen employed their own bootleggers, despite the fact that most voted "dry."

The 18th Amendment had made the manufacture, sale, and transportation of alcohol illegal. It wasn't illegal to possess alcohol—the powerful Anti-Saloon League understood that people would rebel if they couldn't drink the stocks of booze they already had at home. Instead, drys naively believed that people would finish off what was in their liquor cabinets and then simply stop drinking.

But Prohibition didn't snuff out the liquor traffic as planned; instead, it merely deprived buyers and sellers of recourse in the courts when sales went sour. Bootleggers met the American public's undiminished demand for drink with a robust but unpredictable supply. Consumers had no dependable idea what they were buying, often winding up with rotgut industrial alcohol repurposed as "gin"—topped off with water in the bathtub, hence the term bathtub gin—or "Scotch," the same brew blended with some food coloring and iodine.

So Americans were sick (sometimes literally) of Prohibition. But the logistics for repeal were tricky: If Prohibition ended, how should the country control and regulate alcohol? With so much money at stake, and with a robust black market currently controlling sales, it wasn't going to be easy to create a new legal regime.

John D. Rockefeller Jr., a teetotaling Baptist and the richest man in the country, turned his back on Prohibition in a June 6, 1932, letter to his friend, Columbia University President Nicholas Murray Butler. The letter was printed on the front page of The New York Times the next day.

"When the Eighteenth Amendment was passed I earnestly hoped—with a host of advocates of temperance—that it would be generally supported by public opinion and thus the day be hastened when the value to society of men with minds and bodies free from the undermining effects of alcohol would be generally realized," Rockefeller wrote. "That this has not been the result, but rather that drinking generally has increased; that the speakeasy has replaced the saloon, not only unit for unit, but probably two-fold if not three-fold; that a vast army of lawbreakers has been recruited and financed on a colossal scale; that many of our best citizens, piqued at what they regarded as an infringement of their private rights, have openly and unabashededly disregarded the Eighteenth Amendment; that as an inevitable result respect for all law has been greatly lessened; that crime has increased to an unprecedented degree—I have slowly and reluctantly come to believe."

Though committed to the temperance movement, Rockefeller now supported Prohibition's repeal through the 21st Amendment. Rockefeller also proactively sought solutions for how to regulate alcohol once Prohibition ended. The goals: to undermine organized crime and turn bootleggers into law-abiding businesspeople, while ensuring there would be no return to the saloon culture that existed before Prohibition. Rockefeller underwrote a study, published as Toward Liquor Control, that to this day frames how Americans regulate alcohol. The study argued for a three-tier system of alcohol distribution.

Three Cheers for Three Tiers?

The 21st Amendment—better known as the Repeal Amendment—gave states the authority to regulate alcohol. That was one of its selling points to a public still wary of the alcoholic beverage industry. Those states that wanted to stay dry could. In fact, Oklahoma didn't go wet until 1959 and Mississippi legalized alcohol in 1966.

The proposed three-tier system strictly separated the industry into functions. The first tier was the alcohol producers: breweries, distilleries, and wineries. The second tier was the distributors: the middlemen who shipped the product to market. The third tier was the sellers: bars, liquor stores, and supermarkets where consumers bought the finished goods.

Before Prohibition, brewers and distillers produced the alcohol, shipped it to market, and often owned or provided financial backing for the saloons that sold it. Memories of these vertically integrated markets dominated by huge producers made Americans leery of returning to the pre-Prohibition status quo. The so-called tied-house saloons were a major bugaboo of the temperance movement. Booze slingers had offered freebies to workingmen during the day—often thirst-inducing salted pork sandwiches and pretzels—to lure them in to spend their paychecks on beer at lunch. And the powerful producers constantly bullied independent bars, trying to push competitors out of the market.

Prohibition hadn't done much to burnish the reputation of alcohol producers. Makers of distilled spirits were particularly suspect, since hard liquor was generally the bootlegger's drink of choice, as it was concentrated and therefore more profitable than beer or wine. A steady diet of overpriced liquor of dubious pedigree made Americans skeptical about the industry's willingness or ability to return to reasonably priced high-quality goods. State-by-state markets with heavily regulated middlemen seemed like a good way to prevent low-quality products and devious marketing practices.

When Prohibition ended on December 5, 1933, states had to quickly build regulatory frameworks, known as alcohol beverage control (or ABC). Thirty-two states and the District of Columbia adopted Rockefeller's three-tier system, and became known as "license jurisdictions." The other 18 states went further and became "control jurisdictions," whereby the state itself became the retailer, effectively eliminating one of the three tiers.

Getting Loopy on Loopholes

More than 80 years after Prohibition ended, the three-tier system is still the dominant legal framework for alcohol, making it one of the only industries in America where vertical integration is routinely against the law. And it still works, sort of. Alcohol is safe and legal, but the industry remains weirdly distorted by Rockefeller's regulatory compromise. By separating producer from distributor, wholesaler from retailer, the three-tier system obstructs the evolution of 21st century producer-to-consumer relationships (think: farm-to-fork and online sales) while creating artificial scarcity, which in turn reduces choices and competition and increases prices.

To understand how archaic these arrangements are, consider wineries. During Prohibition, people were allowed to brew 200 gallons of wine a year for home use, and the grape market exploded. Most of these were sweet grapes, which made wine taste much more like Coca-Cola. Meanwhile, the actual winemaking industry was devastated. It wasn't until the 1960s that craft wineries began to produce quality wines-three decades after Prohibition ended. They had to work hard to convince wholesalers to distribute their goods, as most people thought the only good wine came from Europe. And they had to lobby states to allow tasting rooms, samples, and the ability to sell wine directly on site. This increased tension with wholesalers, who saw that they would have to compete against wineries themselves.

In order to get around regulatory roadblocks, states where alcohol production is concentrated started pushing open a series of loopholes. California, for instance, which produces about 90 percent of U.S. wine, became home to the nascent wine-tourism industry in the 1970s and '80s and the tourists began asking to take a bottle or case back home, or to join the winery's wine club to get regular shipments.

A number of states created loopholes allowing their own wineries to ship direct to consumer but barring out- of-state producers from doing the same. Another protectionist trick was to require a winery to open an office in a state before being able to ship directly (New York's approach).

But in a landmark 2005 case with direct implications for the three-tier system, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled 5-4 in Granholm v. Heald that states were permitted to either allow or block direct-ship-but they had to do so on a non-discriminatory basis. In other words, allow it for everyone or allow it for no one, but don't play favorites.

Over the long term, consumers have demanded new ways to buy products, and legislatures and regulators have responded. In the wake of Granholm, 40 states now allow direct-ship wine to consumers, so you can get your favorite Napa Valley chardonnay or cabernet sauvignon delivered right to your doorstep.

But this is less a substantial reform than a very large loophole. Direct-to-consumer wine shipments bypass distributors entirely, making these often well-connected middlemen frantic to maintain their regulation-enabled privileges-even though direct-ship only accounts for about 3 percent of the overall wine market. In recent years, the number of distributors nationwide has drastically consolidated, giving alcohol producers fewer choices and less leverage to get their products to market. Volume counts for more than ever, and it can be difficult for a small family winery or a craft brewery to get distribution. In the Internet age of one-click shopping, such gatekeepers may feel like a relic from another era, but they still have political clout.

Growlers for Freedom

Wineries aren't the only producers looking to get around the three-tier system. Brewpubs, which began taking off in the 1980s, not only brew their own beer and sell it to the public—recreating the saloons of yore—but are now allowed in many states to fill up a growler (a large bottle, up to 64 ounces) for home consumption. That makes them producer and retailer all in one, with consumers acting as distributors when they take the beer to go.

Visitors to many brewery tasting rooms around the country can buy a six-pack of beer for home consumption. Cutting out the middleman has proved quite profitable to these small enterprises, providing them with immediate cash flow. They virtually always charge full retail price. (Wineries do the same thing: you'll pay more for their wine in the tasting room than you will in a wine store.)

So even as they rail against regulation, these small businesses often take advantage of the same inflated prices that the three-tier system produces; it's just that they pocket the wholesalers' markup themselves. Consumers enjoying an enhanced experience (such as tasting delicious alcohol in an evocative setting) are usually happy to pay what is effectively the same price—or are so unfamiliar with the inner workings of the industry they don't realize what goes into a price.

Drunk on Booze Money

The three-tier system isn't the only distribution system that has faced challenges. In recent years, two-tier control jurisdiction states such as Ohio, Washington, and West Virginia have made successful attempts to get out from under the state umbrella, or at least to allow the private sector to compete against government-owned stores.

Other states have been less successful. Pennsylvania has tried repeatedly to privatize its 600-plus state stores, but has met strong opposition from package store clerks, unionized state workers who believe they will lose pay and benefits if the system goes private.

Virginia in 2010 attempted to privatize its state-owned liquor stores. Armed with a GOP majority in the state capitol, Republican Gov. Robert McDonnell nonetheless ran up against a wall of money. The commonwealth's ABC stores were making more than $100 million in profits a year for the state, and no economic model shy of greatly increasing the number of privatized liquor stores and raising liquor taxes could replace that lost revenue. (Although increasingly a political swing state, Virginia has many religious conservatives who want no expansion in liquor stores, which they see as a social malady.) Today many Northern Virginia residents trek to the District of Columbia, which has many good liquor stores (all of them privately held), better selection, and lower prices thanks to competition.

States that adopted the control jurisdiction model after Prohibition did so because they believed that the state had a role in espousing temperance and that state package stores would allow better control of distribution. The other key reason was the revenue they knew they'd earn from selling alcohol. Today the temperance justification has withered away, leaving only money as the reason why control states hang on to these outdated liquor stores. Alcohol sales are enormously profitable for these states. They have become reliant on state package store revenue and sales tax receipts to balance the budget.

Consumers don't buy gasoline or jeans from the state, so why should they buy booze from it? Your friendly neighborhood state-run package store might feel like something out of the Soviet era, with unattractive shelving and employees who aren't terribly knowledgeable about the products they are selling. The private sector is far more adept at supplying the market and responding to consumer demands.

Alcohol has always been a fundamental part of American culture. Two-thirds of American adults drink today, and the temperance movement that gave us Prohibition is dead and buried. Alcohol and Prohibition have become chic topics for us to reminisce about; we dress up in 1920s attire and sip once-clandestine cocktails at nostalgic speakeasy parties.

But no one talks much about what we were left with after Prohibition ended, in part because the system and its markups are largely hidden from the end consumer. Choices for consumers proliferate in spite of the tiered systems, which further muddies the case for wholesale reform. And since alcohol regs are—rightly—created at the state and local level, there is no magic federal bullet that can erase the inefficiencies in the system.

The three-tier system was designed for another time and a different social context. Most Americans now drink unapologetically, and the word "temperance" has fallen out of use. But thanks to entrenched interests and general apathy, we're likely stuck with the loophole-ridden status quo for a good while longer.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Exactly what are you a doctor of, Mr. Venkman?

The man is some kind of rodent, I don't know which.

What is the magic word, Mr. Venkman?

My friend, don't be a jerk.

Hold it! I want this man arrested! Captain, these men are in criminal violation of the Environmental Protection Act! And this explosion is a direct result of it!

Yes, its true. This man has no dick.

"Your friendly neighborhood state-run package store might feel like something out of the Soviet era, with unattractive shelving and employees who aren't terribly knowledgeable about the products they are selling."

Yes, it might. On the other hand I have been in privately owned package stores that were as bad as any State store I have ever seen, and in State run stores that had a commendable breadth of knowledge, at least by my (admittedly) limited standards. Salesfolk in State run stores often learn their jobs because they are genuinely interested in Wine (or beer, or whisky), or because they are bored enough to do so in self-defense. And sales folk in private stores are often as dumb as posts, particularly in stores near college campuses or inmhigh-wino areas where the clientele simply doesn't give a good goddamn.

There are reasons for doing away with State run enterprises like State liquor stores, universal awfulness of said stores isn't one of them. It is a straw man.

The plural of anecdote isn't data. It's highly likely that in a competitive environment you would have roughly the same mix of knowledgeable and incompetent liquor store clerks, dependent largely, as you say, on the location and market of the store. If the market rewards liquor stores with helpful, knowledgeable clerks you'll get liquor stores with helpful, knowledgeable clerks. Alcohol isn't the one magical industry where markets don't work.

In fact, the plural of anecdote is data. Data points are just a plurality of things that occurred.

This meme expresses precisely the opposite of the truth.

Data points are just a plurality of things that occurred.

In terms of statistical analysis, yes, but only for large numbers of data points.

Funny how from Va. they'd go to DC for liquor, while my friends in Bristol used to go from the Tenn. side (private liquor) to the ABC in Va. to buy.

I understand the same used to be true of people in Vt. going to NH's state stores. Seems the profits taken by the state by direct ownership were less than the cut taken by taxes in neighboring states.

My understanding is that it's not so in Penna.

Can't help but notice you framed comment in past tense.

They used to go to RI from MA to buy but because the drinking age was 6 months off between the 2 in the progress to 21 back in late 70's, early 80's.

Very well said.

Mencken was unarguably "cranky," but calling him a crank is way out of bounds.

If anything, he was depressingly prescient about the idiocies that assault us every day.

People are so dismissive of great figures of the past, especially when they had imperfections that can be attacked, like Mencken did. Those flaws don't change his importance or his consummate skill at flaying alive people and institutions he thought needed flaying.

Yeah, that jumped out at me too. There is difference.

A, difference.

NO, Mencken WAS a Crank. So am I. A Crank is someone who declines to adhere to any of the prevailing orthodoxies simply because he considers them puerile.

Example; I believe that Gay marriage should be legal. I also believe that, far from being courageous crusaders for Justice, the vast majority of Gay activists who are pushing for Gay marriage are offensive twits who do their cause more harm than good.

Mencken held that Democracy was the theory that the common man knew what he wanted and deserved to get it good and hard.

THAT'S a Crank.

Did you read what Mencken said about Germany and Ludendorff during WWI? Crank is right.

During WWI Mencken (a German-American) felt that America should have sided with Germany (which was arguable) and that Wilson was an idiot (which is demonstrably true) and said so. He also was seriously angry at the anti-German propaganda being passed around as fact in the United States, and this caused him to be rather slow on the uptake when a certain Austrian Corporal established a regime that was determined to live down to that propaganda.

I don't think the "control" argument for state-run stores is entirely dead -- I've heard it here in PA. The revenue hunger of the state (backed by the threat of tax hikes if liquor income goes away) and the influence of the union employees are the most important factors in keeping state stores running, but there's still a prohibitionist constituency out there for whom the flaws of the two tier system remain selling points.

Not just PA. Idaho's constitution Article III:

It's weird how our political thing can coerce laws that are so against the good/wishes of the populace, isn't it? It's like come the 20th century, all that political self-organizing that tocqueville (or whoever that french guy was) described just disappeared.

Why do we put up with it? Everybody thinks that following the law is better than open violent rebellion or even softer forms of it (like mass vandalism, or pointed targeting of enforcers), that the costs of such methods would be worse, but why do they think that? Is it even true? Surely secessionist-type, and/or targeted direct action would not be worse than the massive death and destruction and frustration that the shitty laws cause.

The problem is our political system, the way as it was originally written, actually turned out to be shitty. Republicanism (i.e., having a republic) is crappy if you don't have the direct democracy to back it up. The vague wording in the constitution led to huge federal power and laws being passed without representation (voting for a congressman don't mean shit, we need to vote on the laws, again, democracy). And the party system ensure that only the least principled and most McDonald-esque (i.e. catering to everyone) people get elected, partly with people only voting AGAINST the other guy.

It really just has turned out to be a shitty system. Our classical liberal forefathers were great men with great ideas, but it turned out in the long run to be shitty.

Everybody thinks that following the law is better than open violent rebellion or even softer forms of it (like mass vandalism, or pointed targeting of enforcers), that the costs of such methods would be worse, but why do they think that? Is it even true?

The 600,000-casualty Civil War probably had a little something to do with squelching whatever appetite for violent rebellion was left in America.

Also, bear in mind when you shit on the political system the founders put to parchment that by the time Prohibition came along the constitution had been amended in ways that significantly and fundamentally changed a lot of key aspects of the political system. The most significant probably being direct election of senators and unapportioned direct taxation.

People voting directly for the laws is a good thing in your mind? Have you seen shining California? The state were people vote for laws directly through the propositions process. How is that a good thing?

Well, what's the worst that's happened in California? Just the prop 8 thing.

Just wait till someone puts up a vote to overturn the public schools. Then you'll see the positives. Why nobody has done that yet I don't know, but it should be doable

Well, what's the worst that's happened in California? Just the prop 8 thing.

Yep, prop 8 is literally the only thing wrong with California.

That whooshing sound you hear is your credibility struggling to swirl down the business end of a state-mandated low-flow toilet.

// the three-tier system obstructs the evolution of 21st century producer-to-consumer relationships (think: farm-to-fork and online sales) while creating artificial scarcity, which in turn reduces choices and competition and increases prices.

SNIP: //and increases prices

Yeah, that's kind of the idea. That booze is more expensive helps prevent (a lot of) people from abusing it. I know we all hate to say it, but outside of real addicts with the real natural addiction predeliction, there are still scores of people who are just dumb, and the fact that booze is cheaper would in fact induce them to drink more . Not necessarily more frequently, but more altogether when they do drink, more opportunism to get shit-face, after which they may potentially drive.

And yes, to the extent that I would recommend the law, I am willing to pay more for my booze to help reduce the damage to and from those idiots. (and I get that it also means co-ercing other people to pay more, but in the long run it's hardly the most oppressive law or law with the largest negative effects. Let's deal with zoning, the public schools, environmental reuglation, etc., then let's get on that pure-libertarianism thing)

If you've already accepted that price-fixing toward a social policy end is an admirable and acceptable proposition, you have precious little credibility on which to argue against the other regulations you mention. You do realize that the Bloomberg sodium, soda and transfat bans are supported on identical rationales, right?

// You do realize that the Bloomberg sodium, soda and transfat bans are supported on identical rationales, right?

Except that not everyone in the world is an aspberger douche nerd libertarian who has to see everything through a fucking awkward absolutist concepualist framework. Me saying that making booze expensive is good is the same thing as saying that making food more expensive is also good? Did I say that? Do I HAVE to believe both, just because you claim they're qualitatively the same because they're similar in the broadest conceptual sense? No. That's fucking stupid.

Booze, like other recreational drugs, creates a huge vice problem in society. To any extent that food can be, it's a "first world problem", i.e. not a problem. That's why I can say booze should be more expensive than a pure free market would allow, but food should be left alone.

See? I just said it, and the world didn't explode.

I can also say things like public unions should be gone and public schools replaced with vouchers and private schools, and there should be no anti-development land use controls.

See? I'm still managing to say all these things.

That you want to box things into rigid conceptual frameworks with artificially thick lines doesn't change the fact that I can just believe in things that promote the general good

So you just want to tax the snot out of stuff YOU think is bad for EVERYONE ELSE.

Slaver.

That you want to box things into rigid conceptual frameworks with artificially thick lines doesn't change the fact that I can just believe in things that promote the general good

There is nothing rigid or artificial in pointing out that you are relying upon the exact same reasoning to justify regulatory intervention toward the policy goal of reducing consumption of a good that you don't like as every other asshole on the planet who wants to use regulatory intervention toward the policy goal of reducing consumption of a good that they don't like. It's called having principles. You don't. And you're apparently damn proud of it. So any further discussion would clearly be quite lost on you. I'll happily and proudly stick to being an "asperger douche nerd libertarian" before I turn into a selective fascist.

This is why the first rule of holes is "when you're in one, stop digging". "Fixing" a regulatory problem usually entails creating a thousand smaller ones. We can look forward to the same bullshit in the health insurance and health care industries for the next 15-20 years before we finally give up and go single payer.

But the equivalent hasn't happened with booze. No major jurisdiction in the world AFAIK has gone back to liquor prohibition after repealing it once.

My experience in general is that regulatory reform is good. Fixing a regulatory problem may create 1000 smaller ones, but the key word there is "smaller".

Health care is anomalous in that regard, apparently following a 70-yr. tide worldwide that seeks to redistribute resources to, and within, health care to the needy, which unfortunately is everybody eventually. It's very hard to move health care more toward freedom when the pressure is overwhelmingly toward trying to guarantee care of the highest quality to everyone. Nobody can stand the thought, it seems, of "allowing" anybody to receive care below the highest quality extant. This problem does not exist in the vast majority of other fields.

Ohio has additional nonsense of regulation of wineries as a food safety problem for a license fee and an empirical Food Safety Division. For information or to take action on the unnecessary, duplicate, and discriminatory regulation of Ohio wineries by the Ohio Department of Agriculture, or to support Ohio Senate Bill 32, please see: http://www.FreeTheWineries.com or http://www.facebook.com/FreeTheWineries

United States in 1932, the Great Depression had been underway for three years