Can We End the War on Drugs Without Repealing Prohibition?

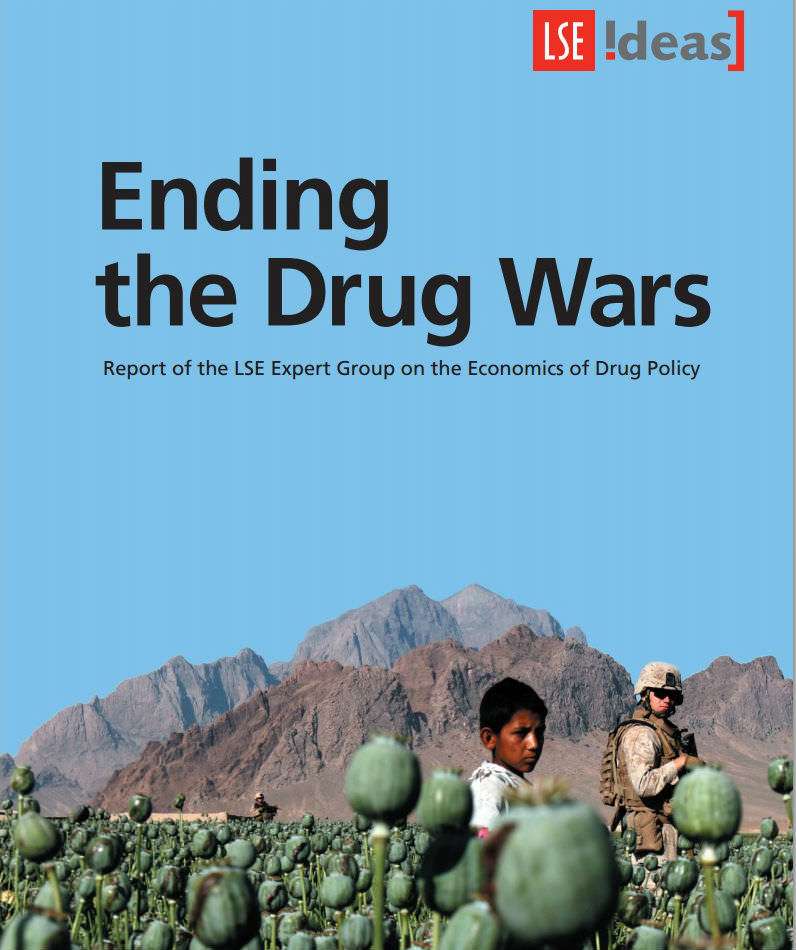

As Matthew Feeney noted this morning, a new report from the London School of Economics (LSE) criticizes "a militarised and enforcement-led global 'war on drugs' strategy" that "has produced enormous negative outcomes and collateral damage." The people who signed onto the call for reform in the report's foreword include five Nobel-winning economists as well as statesmen such as former U.S. Secretary of State George Shultz (also an economist, and a longtime critic of the war on drugs), former Polish President Aleksander Kwasniewski, and former E.U. foreign policy chief Javier Solana. Like the 2011 report from the self-appointed Global Commission on Drug Policy, the LSE report is encouraging as an indicator of opposition to the status quo. But while the new report is much more substantive, offering detailed analyses from leading drug policy experts, it suffers from a similar timidity.

Although the LSE report is titled Ending the Drug Wars, that is not what it actually recommends. Rather than condemning the use of force to stop people from consuming arbitrarily proscribed intoxicants, the report calls for a more judicious use of force, based on more realistic goals, coupled with more drug treatment, a greater emphasis on harm reduction, and tolerance of "global policy pluralism," possibly including experiments with various forms of marijuana legalization. This vision amounts to a decided improvement on current policy, but it would be more accurately described as a de-escalation than "an end to the 'war on drugs,'" as the LSE's press release calls it.

John Collins, coordinator of the LSE's International Drug Policy Project, leads off with a chapter that explains how international cooperation in this area came to be dominated by "a moralistic and supply-centric vision" that left little room for experimentation with other approaches. "The system was built largely upon the assumption that by controlling supply it could control and eventually eradicate 'non-medical and non-scientific' use of drugs," Collins writes. Hence the 1998 attempt "to reinvigorate international efforts by embarking on ambitious targets for demand and supply reduction under the slogan 'a drug-free world, we can do it!'"

Such efforts are doomed, Collins explains, by the economics of prohibition. Attacks on supply may temporarily raise retail prices, but "in a footloose industry like illicit drugs, these price increases incentivise a new rise in supply, via shifting commodity supply chains. This then feeds back into lower prices and an eventual return to a market equilibrium similar to that which existed prior to the supply-reduction intervention." (University of Maryland criminologist Peter Reuter considers evidence of such adaptation in a subsequent chapter on the "balloon effect hypothesis.") "Decades of evidence conclusively show that the supply and demand for illicit drugs are not something that can be eradicated," observes Collins, who recommends "a more rational and humble approach to supply-centric policies."

What would that entail? "If prohibition is to be pursued as a means to suppress the supply of certain drugs deemed incompatible with societal well-being," Collins says, "care must be taken to ensure that enforcement is resourced only up to the point of drastically raising marginal prices to the point where consumption is measurably reduced. After this, additional spending is wasteful and likely damaging." He also cites "a clearly emerging academic consensus that moving towards the decriminalisation of personal consumption, along with the effective provision of health and social services, is a far more effective way to manage drugs and prevent the highly negative consequences associated with criminalisation of people who use drugs."

In the second chapter, Jonathan Caulkins, a professor of public policy at Carnegie Mellon, argues that the war on drugs may not be a failure after all (at least when it comes to "final market" countries such as the U.S.; in another chapter, Daniel Mejia, director of Colombia's Research Center on Drugs and Security, and Pascual Restrepo, a graduate student in economics at MIT, argue that "prohibitionist drug policies are a transfer of the costs of the drug problem from consumer to producer and transit countries," where they result in violence, corruption, and instability). Caulkins agrees that the goal of eradicating the illicit drug trade is "not realistic"; instead, he says, the aim should be to "drive the activity underground while controlling collateral damage created by the markets."

Although prohibition cannot eliminate drug abuse, Caullkins says, it can discourage consumption. Based on that more modest goal, he claims, "plausible" analyses suggest that the benefits of prohibition outweigh the costs even in the United States, which has enforced prohibition in "a particularly pigheaded way," oblivious to diminishing returns. While "prohibition is extraordinarily expensive on multiple dimensions," he says, so is drug abuse, so it's possible that the net impact of the war on drugs is positive.

To illustrate that possibility, Caulkins engages in some half-serious cost-benefit analysis that involves prohibition premiums, demand elasticities, drug use survey data, and quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs). He suggests a scenario in which legalization doubles cannabis dependence while tripling dependence on cocaine, heroin, and cocaine. If you assign a value of $100,000 to each QUALY and assume a "QALY loss per case" of 0.1 for cannabis and 0.2 for the other drugs, Caulkins says, you can show that "prohibition may prevent enough drug dependence to warrant spending as much as $112 billion per year, well in excess of the roughly $50 billion per year now spent on drug control." Even if you throw in $25 billion for the QALY losses of "almost 500,000 drug law violators behind bars" (a subject that Columbia epidemiologist Ernest Drucker considers in his chapter on mass incarceration), prohibition still looks like a bargain, Caulkins says—provided you ignore every other cost associated with the war on drugs, including several that are difficult or impossible to quantify. (Alejandro Madrazo Lajous, a professor of legal studies at the Mexican research center CIDE, discusses some of those hard-to-calculate costs in a chapter about the impact of the drug war on civil liberties in Mexico, Colombia, and the U.S.)

Caulkins admits that his calculation "is extremely rough," although "it has the virtue of being parsimonious." He emphasizes that "the purpose of this calculation is certainly not to argue that prohibition offers a net benefit of $112 billion - $50 billion = $62 billion," since "for many reasons it is not possible to make such a calculation." He explains that "there is enormous uncertainty surrounding every component of the calculations, and intelligent people can disagree about what value to place on averting a year of dependence vs. a year of incarceration." (In their chapter on marijuana legalization, UCLA public policy professor Mark Kleiman and Jeremy Ziskind, an analyst at BOTEC, Kleiman's consulting firm, make a similar point: "It is possible to imagine doing an elaborate cost-benefit analysis of legalising cannabis, but doing so in practice would require one to predict the extent of changes in variables that cannot even be accurately measured in the present, and to perform implausible feats of relative valuation.") The main impression left by Caulkins' discussion is that you can make calculations like this demonstrate anything you want about prohibition, depending on which costs and benefits you decide to include, the way you measure them, and the weights you assign to them.

As Caulkins notes, these decisions are unavoidably influenced by value judgments. For someone who rejects coercive paternalism on moral grounds, no amount of drug abuse prevention can justify forcibly preventing people from engaging in pleasurable activities that harm no one, exposing undeterred drug users to the hazards associated with prohibition, or arresting and imprisoning people for engaging in peaceful, consensual transactions. These burdens are analogous to the costs borne by source and transit countries, since they are imposed on people who do not benefit from them even under paternalistic assumptions.

While the LSE report mentions "human rights" a few dozen times, it emphasizes abuses that occur as side effects of prohibition, as opposed to the violations of liberty inherent in trying to dictate which substances people may put into their bodies. It suggests that criminal penalties for drug users are unfair, or at least misguided, but does not question the justice or wisdom of punishing their suppliers. In the introduction, Collins claims "this report sets out a roadmap for finally ending the drug wars." Yet instead of challenging the moral premises underlying the war on drugs, it ends up advocating what Caulkins calls "a kinder, gentler prohibition."

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

"there is enormous uncertainty surrounding every component of the calculations, and intelligent people can disagree about what value to place on averting a year of dependence vs. a year of incarceration."

Well gee why can't I just have both?

So is this one of those Significant Reports which gets filed and forgotten, except by subsequent researchers? Or is this one of those reports which moves (or reflects) the public mind, thus giving policymakers the space to back off from their dumber ideas?

Its one of those reports with 'interesting and important stuff' that 'clearly needs more research so please give us money so we can keep our phoney-baloney jobs gentlemen'.

Easy answer - no.

Ending the War on Drugs is de-facto ending prohibition. Once the entrapment and enforcement apparatus that's been built up to enforce prohibition is gone then so is any teeth to prohibition. There is no carrot here, only stick, and once that stick is gone there's no way left for you to stop people from using 'illegal' drugs.

Why cant they just admit they don't want to lose their women to the jazz man? Prohibition lite is still an evil endeavour. Baby steps I guess.

There are not just costs to the drug war. There are also lost opportunities and benefits. We're already seeing an incredibly diverse weed industry springing up in CO and hopefully soon here in WA. The amount of economy-boosting that would be done by ending prohibition--besides the removal of costs--would be staggering. Stopping people from doing business that they'd like to be doing is part of stopping people from doing drugs they'd like to be doing.

The cost of the War on Drugs, both costs and lost benefits, is monstrous.

here are also lost opportunities and benefits. We're already seeing an incredibly diverse weed industry springing up in CO

But, entire portions of the city have been wiped out by sky rocketing hash oil explosions! Don't you go outside, or read Drudge Report?

I can't see through the haze of smoke from the weed factory explosion here in Seattle.

Um, drugs r bad, mmmkay?

You forgot the obligatory

/Chief Storm Trooper Leonhart

I haven't RTFR, but one thing that raises my eyebrow in these cost-benefit analyses is that they leave out so many things that should be factored in. Typically, they'll talk about the cost of incarceration versus the costs of increased medical care and decreased labor output. But one thing they don't talk about is freedom - the freedom to smoke a joint if you want to, to walk onto a plane without getting your nuts grabbed, the freedom to open up a pot shop if you want. The converse of the freedom (benefit) is the fear (cost) of being searched and thrown in a rape cage by the gub-mint.

I'm not a utilitarian, but any cost/benefit analysis that leaves out psychic factors like freedom and fear is woefully incomplete. Ultimately, all costs and benefits devolve to psychic ones (viz., wealth is valuable only because people derive psychic enjoyment from its use).

Unless they plan on eliminating the DEA, neither the end of prohibition nor the war on drugs is going to happen. Their entire job at the DEA is predicating on there being something to enforce. That's 10,000 well connected Federal agents with reams of dirt on a variety of high level politicians who are not going to give up their "life's work" for nothing.

"I can tell you that for me and for the agents that work for DEA, mandatory minimums have been very important to our investigations..."

They won't even listen to the President. We'd have an easier time eliminating the Department of Education.

They won't even listen to the President

Why should they? All of these agencies have been made totally unaccountable to anyone, and given their own personal armies to back up their little rogue empire.

The DEA has a $3 billion a year budget(FY2012)[1], reported, who knows how much more they tied up in various legal actions and "investment allocations".

I don't blame the Forestry Department saying "If they get a tank we should get a tank too." This is how government operates.

Next thing you know you're talking real money.

Tanks for everyone!

Much like the Dept. of Agriculture now acts mostly processing food stamps and doesn't do much agriculture, the DEA will mission creep away from contraband drugs and move into regulatory enforcement of drug consumption or something.

They'll have twice the budget, be embedded in every hospital waiting room and drugstore. A DEA agent will assist you in your health selections experience. And if you don't finish all of your antibiotics like the doctor tells you, a tank will execute a compliance order on your ass.

He suggests a scenario in which legalization doubles cannabis dependence while tripling dependence on cocaine, heroin, and cocaine. If you assign a value of $100,000 to each QUALY and assume a "QALY loss per case" of 0.1 for cannabis and 0.2 for the other drugs, Caulkins says, you can show that "prohibition may prevent enough drug dependence to warrant spending as much as $112 billion per year, well in excess of the roughly $50 billion per year now spent on drug control." Even if you throw in $25 billion for the QALY losses of "almost 500,000 drug law violators behind bars"

The church of warmology needs this guy to cook up a few whoppers like this, for them. Because apparently, their whopper cookers aren't getting the job done way they are losing credibility so quickly these days.

I don't know what you're talking about. The US never had floods or droughts before global warming. Never.

They never had the coldest first 4 months of the year in recorded history either, before this year. So see, cold proves warming, I mean change, I mean disruption, I mean weirding, what they fuck ever they are calling it this week.

Whatever they're calling it this week, the cause doesn't need to be proven, or labeled, or whatever to make the proposed cure a wise decision. There's a good reason why guppies eat their young.

Why is it that people have to have proof that keeping the environment clean is a good thing for the long term? The really sad thing is that it just isn't that hard. Oh well, it doesn't really matter, I'll be dead decades before the consequences of that denial are manifest. I chose not to reproduce a long time ago and I sure don't care if your kids/grandchildren/etc suffer because of your short sightedness. You do realize that by the time the proof you demand exists that it's going to be too late, don't you? And all because you're too lazy to clean up after yourself.

Oh. My. God. A United States with twice the marijuana use and triple the cocaine use?!?

That would be 1979. Well, close to double on pot and actually quadruple in coke:

Past 30-day Marijuana Use 1979 = 12.8%

Past 30-day Marijuana Use 2012 = 7.3%

Past 30-day Cocaine Use 1979 = 2.4%

Past 30-day Cocaine Use 2012 = 0.6%

Heroin use is up - 0.13% now vs. 0.08% in 1979 and approaching the 1997 high of 0.15%. But the mass increase in oxycodone production quotas starting in 1997 from a few tons to hundreds of tons now has something to do with that.

Drugs and global warming are all we have to worry about. No need to worry about an out of control federal government spawning exponential growth in unaccountable bureaucracies with their own swat teams and tanks. No siree, nothing to see there, move along now.

See the drug war worked.

/ prohibitionist dipshit

"This new global drug strategy should be based on principles of public health, harm reduction, illicit market impact reduction, expanded access to essential medicines, minimisation of problematic consumption, rigorously monitored regulatory experimentation and an unwavering commitment to principles of human rights."

Self-ownership unfortunately not included, human rights meaning "whatever we deem human rights to be in this era."

"This new global drug strategy...". KlanD, spot on. Unfortunately when you collective healthcare, education, retirement funding etc the people funding the programs suddenly have the right to tell the recipients how to live.

Basically, we (the bullshit pronoun psychopathic politicians use when spending taxpayer money) paid for your fabulous public education. Therefore we insist you don't smoke a J. You have no self-ownership in that cycle of logic.

There's a moral hazard to being the profiteer of other people's misery.

Ask anyone: Why is it that the US can't control Drug substances but have a great deal of control of C4? The Answer is always that the DEA/FBI/POLICE are being bribed in some way/shape/form by the Drug Criminal Enterprise. In addition to that, how many police officers, correction officers, and parole officers enjoy a nice pension, salary, and benefits for the $50k a year it takes to lock up non-violent drug offenders? These are the people I speak about that are the profiteers of other people's Miser.

I have a solution to our Drug War and Drug Problem if I can only get the Mayor of NYC, the Governor of NY State, and the President of the United States all agree order their respective Justice Departments NOT to enforce the Drug laws.

I would give the DRUGS away for FREE. No more BRIBE MONEY Mr. Officer. And No need for the Prison Complex. And the addict won't have to rob or suck dick for money.

You really don't look as good in the tutu at age 65 as you did at 30. Almost as ludicrous as a geriatric Black Sabbath.

But all non-violent drug offenders eventually become violators of others. Didn't you see Reefer Madness?

I'm wondering if "I would give the drugs away for free." means you personally would or you would mandate producers give away their product. Now, now. Bad libertarian.

Alice Bowie is all over the fucking map. Sometimes libertarian, sometime fascist, always insane.

Besides the executive won't stop enforcing laws voluntarily. You have to strip it of its power.

Exactly.

Exactly.

Caulkins circular logic calculations are more like a Mandebrot set for prohibition. Repeating patterns of unsuccessful tactics ad infinitum.

I have heard better "what if" scenario's in the waiting room of the local mental health clinic.

Prohibition is a morally bankrupt idea that has eaten away at the foundation of liberty that this country rests upon. Caulkins only adds to the disaster that prohibition is by suggesting ways to prolong its degrading and destructive influence.

No mention of PTSD.

The Drug War is something created by the older generation, and will only change as they pass from political power into history. Evolution of political thought is in many ways no different than advancements in science - which Max Planck once described as progressing "one funeral at a time." Very prescient.

You can already see that with folks like Obama, who grew up with the Drug War instead of observing it. Of course he's a hypocrite, and old-timeys still vote a lot, so he betrays what he believes with his drug-shtick. But like everything else about the charlatan, as the polls go so do the pols; pretty soon Hillary will be talking soft on drugs - at least poll-tested ones like dope.

It is truly amazing how effective anti drug propaganda was on people born in the 40s, 50s and early 60s.

"intelligent people can disagree about what value to place on averting a year of dependence vs. a year of incarceration." - Jonathan Caulkins

This type of analysis is sick because it reduces a person to some variable in an equation. The value of someones loss of liberty can only be made by themselves. In a just world, this type of social analysis would be treated with the same horror that Cliven Bundy's was:

"And I've often wondered, are they better off as slaves, picking cotton and having a family life and doing things, or are they better off under government subsidy?"

Disgusting! They want our children use drugs. How can it be possible?

Both war and prohibition have only one purpose.

Profit!