Book Censorship Spiked in 2013

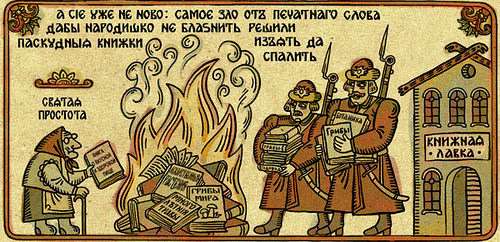

Censorship of books rose dramatically in the U.S. in 2013, according to a major watchdog and advocacy organization.

The Kid's Right to Read Project (KRRP), an arm of the National Coalition Against Censorship, reports that, compared to last year, it has investigated 53 percent more cases of books being "challenged." Shelf-Awareness, an industry newsletter, states that in November alone, KRRP "investigated three times the average number of incidents," and that "during the second half of 2013, the project battled 31 new incidents, compared to only 14 in the same period last year." In total, they've grappled with 49 incidents in 29 states. Luckily, many of their efforts have successfully put books back on the shelves.

KRRP coordinator Acacia O'Connor told the newsletter, "It has been a sprint since the beginning of the school year," said O'Connor. "We would settle one issue and wake up the next morning to find out another book was on the chopping block." She highlighted that the majority of books that were challenged dealt with sensitive topics like race and sexuality.

The KRRP warns of the serious repercussions that come with restricting children's access to literature:

Censorship is about more than a single book. It is about the intellectual, cultural and political life of the community and the people in it.

Each time a book is a removed it reinforces the idea that books and ideas are off-limits if someone doesn't like them. It contributes to a culture where it's better to hide from controversial or difficult topics, than to acknowledge or discuss them.

[…]

It's censorship whenever anyone in the government – including public schools and library – restricts access to a book because they dislike it or disagree with what it says.

Who is trying to ban books? "Most of the challengers were parents of district students or library patrons, though a handful were local or state government officials," according to The Guardian. As little provocation as a single complaint can take books out of classrooms. A notable case of this happened to Neil Gaiman's Neverwhere in a New Mexico high school in October.

Although the advocacy group suggests that determining the merits of a book should not be left up to "squeaky wheels" or "majority opinions," they believe in "the professional judgment of individuals with training and expertise." This stance, unfortunately, also falls short of actually preventing censorship. The real way to protect books is by not putting authority in the hands of any, but by allowing each individual to decide for himself—and only himself—what information he consumes.

Show Comments (122)