5 Big Questions About President Obama's Health Law Tweak

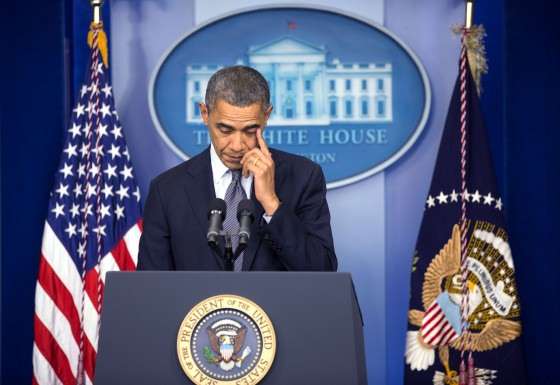

Earlier today, President Obama announced a plan to tweak Obamacare by allowing state insurance commissioners to let health insurers continue to offer plans that do not pass muster under Obamacare's health insurance regulations. The announcement came following mounting public outrage about the millions of individual market health plans being terminated as a result of the health law's regulations—in direct contradiction to the president's repeated promise that people who liked their health plans could keep them. Congressional Democrats had been circling around plans to address plan cancellations all week; the announcement was in large part a response to growing pressure from within the president's own party to respond.

But the president's plan doesn't resolve the mess. Indeed, it may have just compounded the law's existing political and policy troubles. Big questions remain about how it will work, and how other parties will respond.

1. Will congressional Democrats be satisfied? The president's tweak was designed to help congressional Democrats under fire for supporting a law that caused people to lose their health plans despite many absolute promises to the contrary. But while some Democrats appear to be happy with the change, which allows them to blame insurers for cancelling plans, it's not clear that this will placate all of them. Sen. Mary Landrieu (D-La.), who sponsored a bill to require insurers to continue existing plans, said in a press conference this afternoon that the president's proposal was a "step in the right direction," but also suggested that a further legislative fix might be needed.

2. How will the insurance industry react? This is potentially a big deal. Right now, the insurance industry is working closely with the administration, and despite frustrations with the rocky rollout of the exchanges, has largely avoided direct confrontation with the administration. Not so here. The head of America's Health Insurance Plans (AHIP), issued a statement warning that the president's plan could upend the insurance market. "Changing the rules after health plans have already met the requirements of the law," said AHIP CEO Karen Iganagni, "could destabilize the market and result in higher premiums for consumers." That, in turn, could have political consequences, as next year's insurance rates will be revealed in the months leading up to the 2014 election.

3. How will the new policy be implemented? A letter sent to state insurance commissioners says that the Obama administration will allow health insurers to "choose to continue coverage that would otherwise be terminated or cancelled" next year under a "transitional" policy. But that still depends on the say-so of state insurance regulators, who are merely "encouraged to adopt the same transitional policy" regarding specific types of terminated coverage. Yet insurance regulators aren't sure how to do that. "It is unclear how, as a practical matter, the changes proposed today… can be put into effect," said the head of an insurance commissioner's group, according to a Wall Street Journal health reporter. So there's a significant operational question about how—and whether—this would work.

4. Will state insurance commissioners actually pursue the Obama administration's encouraged change? Maybe not. At least one has already said no thanks: Washington state Insurance Commissioner Mike Kreidler, one of the most liberal insurance regulators in the nation, has already indicated that his state won't participate, citing "serious concerns" about implementation and insurance market stability. Washington state, notably, has had direct experience with insurance market meltdowns in the past: In the 1990s, it passed a slew of health insurance market reforms that eventually resulted in the large majority of individual market insurance carriers exiting the market.

5. Is it legal? Right now the administration is citing "transitional" authority to implement the change. But it's all pretty vague. The idea, as with the delay of the employer mandate, is that transitional authority gives the administration the power to do what is necessary in order to put the law in place. But the power to take the steps necessary to implement a law doesn't obviously apply here. What the administration is doing is using its authority to not implement a part of the law.

Show Comments (83)