Why Aren't People Grateful for the Better Health Plans (or Light Bulbs) Mandated by the Government?

The New York Times notices that the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act—under which, President Obama assured us, we could keep our health plans if we liked our health plans—has resulted in the cancellation of medical coverage for "hundreds of thousands of Americans in the individual insurance market." But the article treats this phenomenon mostly as a Republican talking point, as opposed to an actual problem. "Cancellation of Health Care Plans Replaces Website Problems as Prime Target," says the headline. "After focusing for weeks on the technical failures of President Obama's health insurance website," says the lead, "Republicans on Tuesday broadened their criticism of the health care law, pointing to Americans whose health plans have been terminated because they do not meet the law's new coverage requirements." The Republicans even have props:

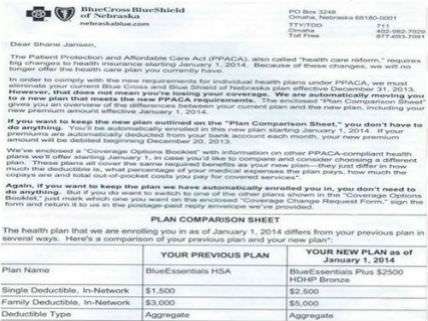

Baffled consumers are producing real letters from insurance companies that directly contradict Mr. Obama's oft-repeated reassurances that if people like the insurance they have, they will be able to keep it….

The cancellation notices are proving to be a political gift to Republicans, who were increasingly concerned that their narrowly focused criticism of the problem-plagued HealthCare.gov could lead to a dead end, once the website's issues are addressed.

The Times does intimate that canceled health insurance is perceived as a problem by those who experience it but repeatedly suggests that it's not that big a deal. "The affected population, those who bought insurance on their own, is a small fraction of an insurance market dominated by employer-sponsored health plans," it says. (Won't the government's new minimum coverage requirements force changes in those plans too, and won't that result in higher costs for employees?) "Tens of millions of people are finding that their insurance is largely unchanged [except for the cost?] by the new health care law," a sidebar notes. What about the others? "In many of those cases," the Times says, "the insured have been offered new plans, often with better coverage but also at higher prices." At a House Ways and Means Committee hearing yesterday, Marilyn Tavenner, administrator of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, likewise emphasized (as paraphrased by the Times) that "the new policies would provide more benefits and more consumer protections than many existing policies."

Tavenner seems to think that makes it OK to force people out of their old policies and into the new, government-approved ones. Yet people who buy coverage on the individual market already have weighed the tradeoffs and decided they do not want the benefits that the federal government insists they should have. Overriding those judgments is like demanding that car buyers looking for an economical subcompact buy a hybrid minivan instead. Sure, it costs more, but it's a better vehicle! Look at all that space for children! And if the buyer happened to be a bachelor, he would be in the same position as all the people compelled to buy "maternal coverage" or "substance abuse services" for which they have no use.

Even features that pretty much everyone would like if all other things were equal, such as low deductibles and generous prescription drug coverage, cost money. People who deliberately forgo them have decided they are not worth the price. By what right does the government tell them they are wrong?

The argument that the insurance mandated by Obamacare costs more, but it's worth it reminds me of the debate over the creeping federal ban on incandescent light bulbs. There, too, consumers had made a choice that politicians and bureaucrats did not like: They overwhelmingly preferred traditional bulbs, despite their inefficiency, because they were much cheaper than the alternatives. But consider the energy savings! "A household that upgrades 15 inefficient incandescent light bulbs," an Energy Department official enthused, "could save about $50 per year." Consumers unimpressed by that calculation were clearly too stupid to be making decisions for themselves, so they had to be forced into better (albeit more expensive) choices.

Editor's Note: As of February 29, 2024, commenting privileges on reason.com posts are limited to Reason Plus subscribers. Past commenters are grandfathered in for a temporary period. Subscribe here to preserve your ability to comment. Your Reason Plus subscription also gives you an ad-free version of reason.com, along with full access to the digital edition and archives of Reason magazine. We request that comments be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment and ban commenters for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

You're surprised American Pravda is shilling for the law? Only Kulaks are losing their decadent insurance plans! The New Obama Man is happy to pay more for something they don't want.

"The affected population, those who are gay and want to marry, is a small fraction of a marriage market dominated by opposite sex couples"

Alt-text: "There's no sugarcoating it. You had a mild aversion to your old plan."

"You're getting a new plan, at twice the price, and you're going to like it. get over it, loser. Elections have consequences."

If the cost were the same, it would be the same plan, if the benefits were the same.

Sounds like ....

If I had some ham, I could have some ham and eggs, if I had some eggs.

..."has resulted in the cancellation of medical coverage for "hundreds of thousands of Americans in the individual insurance market.""

Technically correct, since millions is also 'hundreds of thousands', but a sleazy misdirection worthy of lefties anyhow. The CA gov't admits to 900,000 cancellations, and it's a good bet that's a lie also.

http://blog.sfgate.com/djsaund.....s-on-1231/

Local news reported that 800,000 policyholders in Jersey got cancellation notices. That's just Jersey. It's got to be over a million nationwide.

Insurance was always regulated at the state level. OC regulates a minimum standard at the federal level over and above what was previously allowed in many states. The standards are close to what's written in NY - which has been a disaster to the individual market there.

This was always about the feds taking over what was a state's responsibility.

Not shocking, states with fewer minimum benefits have less expensive alternatives.

NJ = an admitted 800K, CA = an admitted 900K; two states = 1.7M.

Oh and:

"As is apparent from this discussion thread, it's simply not worth trying to engage right-wingers and their political masters in an honest discussion about health care. They've made that impossible by unilaterally withdrawing from the realm of honest discourse. They're flogging phony issues, deliberately misconstruing the facts and basically lying about every aspect of the ACA, because their only concern is causing political problems. That's their only agenda...."

http://blog.sfgate.com/djsaund.....s-on-1231/

See, it's just those tea-baggers! Everything would be fine if they didn't focus on those phony issues!

Mostly OT: My metro councilcritter just decreed that Halloween will be celebrated on Friday 11/01 because the forecast is calling for rain on Thursday. Is there no problem too small to be solved by authoritative decree?

I'll be in full Clint Eastwood mode when the first kid knocks on my door Friday.

.... just decreed that Halloween will be celebrated on Friday 11/01 because the forecast is calling for rain on Thursday. Is there no problem too small to be solved by authoritative decree?

Why didn't he just decree that rain in all forms (regular, drizzle, deluge, etc.) would be prohibited on the 31st? It seems to me that this is a more reasonable approach.

And since we have a right to life, why not outlaw death?

Fuck it Sevo....

I propose the omnibus "I Decree It Obvious That....." Bill that will henceforth prevent anything bad from ever happening to anyone! Yes...if we only pass this "IDIOT" bill then among other things your teeth will whiter, you'll have greater sexual appeal and stamina, you'll be taller, never suffer from hangovers, have a flat tire, or miss a connecting flight....and your clothes will be springtime fresh....forever!

full Clint Eastwood mode

Which movie? Dirty Harry? Outlaw Josie Wales?

Bronco Billy.

I think he means that he'll be talking to his chair.

Paint Your Wagon

Definitely Gran Torino.

The cancellation notices are proving to be a political gift to Republicans

Holy fuck, these people are despicable.

It wouldn't be such a big deal if it didn't cause people to vote for Republicans.

Yup, disgusting. The cancellation notices aren't a problem fir the people that get them, they're a problem because they might help the GOP.

How could they be a problem for the people who get them? Those are bad policies. They needed to be replaced.

See also: every single Obama scandal framed as "Republicans use X to attack President".

Yes, the worst thing about this is that it's good for Republicans.

Not the fact that people who were responsibly enough to buy their own coverage, and had a product they could afford and were satisfied with are having their coverage canceled and being forced to pay more.

What's bad about this is that REPUBLICANS might benefit from it.

why not outlaw death?

Perfect.

"Your father died illegally. We're confiscating his assets. You can see yourself out."

I'd forgotten about the McGovern plan.....

Slightly OT:

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/fem.....NKIES.html

Ahem...

I don't really get pointing out "substance abuse treatment" as being something that lots of people woul obviously opt out of.

Most people who need such services never expected to hav to use them. Even a teetotaler might find themselves addicted to prescription drugs.

The requirement that men purchase maternity coverage is laughable and deserving of scorn and derision.

*disclaimer: obviously all government mandates are bad, I am merely discussing the tactical value involved in the rhetoric.

Tactically speaking, if most people don't think they'll ever need substance abuse treatment, then it is a good idea that to point out that they are being forced to buy it.

In the days when insurance companies were actually MUTUAL companies, I would refuse to apply to a mutual company with members who DO think they will eventually need substance abuse coverage.

Do you see anyone out there going "Yay! Now I have substance abuse treatment, which I didn't have before! Thanks ObamaCare!" ?

Do you see hordes of people complaining because their insurance doesn't cover substance abuse treatment?

No, you don't. And do you know why substance abuse treatment is REALLY being covered? It is so that the Democrats can jack up the price of the average premium, so they can force people to pay more into the system, so they can use the money to pay for healthcare for other people. NOT for substance abuse treatment. It is purely so they can CHARGE PEOPLE MORE to transfer more money from the healthy to the sick.

People who don't like drugs probably aren't going to find themselves unexpectedly addicted to drugs. Everyone who takes opioid pain killers for any extended period is going to become dependent on them and feel crappy when they go off of them. But those aren't people who need treatment. People without addictive personalities really are never going to need substance abuse treatment. The idea that anyone could become an addict through bad luck or whatever is one of the sillier myths about drugs.

Obamacare: The low flush toilet of healthcare!

+100

It doesn't do shit and it's not going away?

Perfect.

At least for now you can keep your old toilet if you like it.

"By what right does the government tell them they are wrong?"

Too easy... FYTW

The advance of civilization can be measured by the increase in the degree to which the common man can get away with telling his "betters" to go piss up a rope and stand under it while it dries.

So you're saying we're not very advanced.

Regression 🙁

Central planning fails for a lot of reasons. One reason is the information problem Hayek describes. The other big reason is that you cannot know how people value things. Even Libertarians fall into this trap sometimes by assuming everyone is homoeconomicus and values money and efficiency over things like security or immediate gratification or status.

What happens is planners go out and do a cost benefit analysis assuming that everyone values things just like they do. I value saving water over a perfect toilet flush, so everyone else must too. I want my health plan to cover everything and I am okay with paying more so others can have coverage, so everyone else must want that too.

Of course what each individual actually wants is an incredibly individualized decision based on their values and perceptions at the time. So the planners are always going to get it wrong because not only do they have no way of knowing all of those calculations, they have no way of accommodating all of them.

"Of course what each individual actually wants is an incredibly individualized decision based on their values and perceptions at the time."

I'm pretty sure that IS 'the knowledge problem', and it's what is solved by price signals.

It is a bit different than that. The knowledge problem is that you can never know in the aggregate what people want. I have no idea how many pencils the country is going to want next year so my five year plan for producing pencils next year is assured of being wrong absent incredible dumb luck.

What I am talking about is on a more individual level. Even if knew how many pencils the country as a whole would want, I have no way of knowing how badly you want one or what kind of pencil you want. I can't know and cater to everyone's preferences. More importantly, I can't even predict what people's preferences will be. For that reason I can't make a general rule like "everyone who works in an office gets a free pencil" without producing the absurd result of giving goods to people who don't want them while depriving them from people who do.

"It is a bit different than that."

Disagreed. The number of pencils is exactly related to personal preferences.

I want *orange* pencils, and if you don't have those, I'll take pens. Your pencil count is off.

Yes it is. But even I get the numbers right, I can still give them to the wrong people. And that bureaucracies always do because bureaucracies operate by rules and never are able to handle individual cases.

I just see this scenario with Satan played by the State.

Substance abuse treatment? Nobody needs that.

The government provides it for nothing, while you're in jail.

Tavenner seems to think that makes it OK to force people out of their old policies and into the new, government-approved ones

See suffers from the typical Liberal trait of evaluating something based solely on its benefits, while openly ignoring costs.

I with the Government would force me to buy a Maserati. Because that would be better than my current shitkicker.

Economic freedom IS freedom. Most Democrats and many Republicans oppose freedom of any kind.

That is not true. Most people love freedom right up until someone they don't like exercises it in a way they don't approve of. It is endemic to all people, even the philosopher kings known as Libertarians.

It's the new Tulpa!

Yeah because Libertarians are a special breed of smarter and more moral types than everyone else. They are never prone to the same faults as others. No. They are the new Superman!!

Do you believe that? If not, then why is what I am saying wrong?

Flog the straw man! Run with the goalposts! Tulpafy!

I'm a bit taken back and surprised that John hasn't yet realized we are a superior race of men even after years of exposure, but then even Arjuna was obstinate in the face of Krisna's glory.

It's wrong because we don't object to freedom, if I may generalize for a minute. Libertarians don't advocate for legislation based on personal preference; we advocate for the basic principle of liberty.

SLD: No True Libertarian...

"That is not true. Most people love freedom right up until someone they don't like exercises it in a way they don't approve of."

Um, but that is not very libertarian. CE's point stands, as he was saying TEAM folks DO dislike freedom...but this here bunch of freedom respecters, that is why we are libertarians.

There are very few people who respect freedom. Very few. Most people respect freedom for people they like. They may pay lipsservice to the rest. But it is maybe one in a hundred who will actually stand up for the freedom of someone they don't like. It doesn't matter what side they are on. It is human nature.

You're not completely wrong.

I am a beleiver in total freedom. This pretty much ends up in me being seen as an anarchist, even though I disbelieve in anarchy as an actual concept.

Every libertarian I know (other than my wife, who I have taught over many years to think like I do) feels the need for at least a few VERY restrictive laws. I don't agree.

I think absolute lawless freedom is the base, correct way the world should work. Any rules we add to that clean slate just muck up the pure, simple freedom that it entails.

Of course, as a reasonable modern person, I can easily understand why my viewpoint wouldn't work out particularly well with modern society. I am willing to make exceptions, though they stick in my craw.

By what right does the government tell them they are wrong?

Are you really looking for an answer to that?

I feel this urge to troll some liberal boards, replying to every defense and deflection with "If you like your current plan, you'll be able to keep it."

DO IT

I won't stoop to their level.

I would...

He never said that Sugarfree. Obama said you could keep your plan if it complied with the law. Everyone knew that is what he meant. And we had an election in 2012 that was a referendum on it.

It is the law you tea baggin terrorist.

There Sugar Free. You don't even have to read the responses now.

Soooo...wish I didn't agree with you.

Yes, also, we won, elections have consequences, so you'll get your free colonoscopy, and you'll like it. Bend over.

I have a better one.

But, now your plan covers a FREE COLONOSCOPY. Just relax and accept it.

I actually needed a colonoscopy recently.

So, that hurts my feeling.

And my butt.

So, no "a-ha" moment at the New York Times.

Check.

Tens of millions of people are finding that their insurance is largely unchanged [except for the cost?] by the new health care law

A blatant lie, greased along by the weaselly "largely."

Very few plans have not been changed by the ACA. Apparently, though, the best defense of the ACA now is that it didn't really change much? Seriously, that's your legacy-defining fundamental transformation?

But think of the tens of people who now have health coverage who didn't have it before.

I wonder how long until we are told that what Obama really said was "You can keep your plan if we like it."

That is what they are saying right now. If they like it, it is clearly what is good for you.

I was just thinking the exact same thing.

If the new plans people are being forced to buy as so much better, why do we not hear reports of people having their plans canelled and they going "But the new one I got is so much better and cheaper! Yay!"?

NOBODY is saying that. People who are losing their plans are universally pissed off and saying their new rates are higher and/or their coverage is worse.

The only people saying the plans being canceled are crap are ObamaCare flunkies who have no idea what they are talking about. People repeating the idiotic lie that a few free preventive care visits per year makes up for hundreds to thousands of dollars extra in annual premiums.

People were HAPPY with those plans. They weren't feeling screwed over. They weren't having problems with denied claims. They had a product that they were SATISFIED WITH.

And then they go online and discover people telling them things like "We won, so there." or "Everyone knows there would be winners and losers, and you are one of the losers."

And to top it off, the people this is happening to aren't people who were uninsured and cost shifting, these are, largely, middle-income people who were taking responsibility for buying their own health plans. And now they are being punished and being forced to pay for care for people with pre-existing conditions.

They weren't having problems with denied claims. They had a product that they were SATISFIED WITH.

I think you've missed the point here. The idea is for government to make you dissatisfied with that which you were satisfied, and then come back to you claiming they have a solution.

Obamacare is phase one. Wait 'til you see phase two.

Underinsured is the new SLAVERY!

At least I can get free birth control now.

When can I get muh free mammogram!

Go to the nearest OFA office where you can get your free colonoscopy courtesy of your friendly neighborhood progressives.

Actually, the colonoscopy costs you money, and it's not really something you volunteer for, if you get my meaning.

But, Paul, it's "free" preventive care.

Come the Revolution, EVERYONE will get free colonoscopies.

My doctor keeps telling me, 'you can let go now. PLEASE, let go.'

Not like its our first date, bitch. Now wiggle it around and make me giggle.

I really should have a female doctor. Not for the obvious reason, but because I behave much better for women.

I behave much better for women.

Don't we all.

Isn't it amazing that we, the great unwashed, are too moronic to pick out our own clothes in the morning, let alone our insurance plans or lightbulbs, but we were brilliant enough to vote for the Lightbringer -- twice?

Or maybe that's just one more manifestation of our mental defects.