Thanks to NSA Surveillance, Americans Are More Worried About Civil Liberties Than Terrorism

Last week's narrow House vote against the Amash Amendment, which was aimed at stopping the National Security Agency's mass collection of Americans' phone records, reflects a narrow split among the general public. The vote was 217 to 205, meaning that 49 percent of the legislators who participated wanted to end the program, while 51 percent wanted it to continue. Similarly, the latest Pew Research Center survey, conducted over the weekend, found that 44 percent of Americans oppose "the government's collection of telephone and internet data as part of anti-terrorism efforts," while 50 percent support it; the rest were undecided or declined to answer. A month ago in the same survey, 48 percent were in favor and 47 percent were opposed. While that shift suggests a slight increase in support for NSA surveillance, the new survey also found that 47 percent of Americans worry that counterterrorism policies "have gone too far in restricting civil liberties," compared to 35 percent who worry that they "have not gone far enough to protect the country." According to Pew, "This is the first time in Pew Research polling that more have expressed concern over civil liberties than protection from terrorism since the question was first asked in 2004."

It is no wonder that concern about civil liberties is rising when you consider some of the other opinions endorsed by respondents. For instance, 56 percent said the federal courts "do not provide adequate limits on what government can collect"; 70 percent said "the government uses [these] data for purposes other than terrorism investigations"; 63 percent thought the government is reading email and listening to calls, rather than just looking at metadata; and 56 percent said "the government keeps too much information about its anti-terrorism programs secret from the public." Given the level of distrust reflected in these numbers, it is surprising that half the respondents still expressed overall support for "collection of telephone and internet data" in the name of fighting terrorism.

There was a sadly predictable partisan split in opinions about government encroachment on privacy, with 57 percent of Democrats supporting the surveillance programs, compared to just 44 percent of Republicans. Notably, Democrats in the House were less blindly loyal to President Obama in the vote on the Amash Amendment: 57 percent of those who voted supported the amendment, compared to 41 percent of Republicans, essentially the reverse of the pattern seen in the Pew poll.

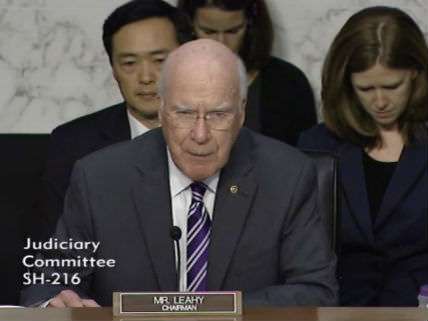

Although the most recent Pew survey did not ask specifically about the indiscriminate collection of telephone metadata, a month ago 56 percent of respondents said they were OK with "secret court orders to track telephone call records of millions of Americans in an effort to investigate terrorism," while 41 percent disapproved. I suspect the latter group will grow as it becomes clear that the government has greatly exaggerated the usefulness of the phone-record database in preventing terrorist attacks. "I have not seen any indication that the bulk phone records program yielded any unique intelligence that was not also available to the government through less intrusive means," Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore), said in a speech last week. "If this program is not effective," Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.) said at a hearing yesterday, " it has to end. So far, I'm not convinced by what I've seen." He said Obama administration officials has shown him a classified list of "terrorist events" supposedly prevented by NSA surveillance, and it did not support claims that "dozens or even several terrorist plots" had been thwarted thanks to the phone record dragnet. The New York Times notes that the 54 successes intelligence officials originally attributed partly to the database have become 13 investigations to which the database "contributed." That phrasing leaves open the possibility that the database was not actually necessary, especially since the same information could have been obtained through court orders aimed at particular targets.

Show Comments (33)