What Gets a Bad Cop Punished? How About Intimidation, Abduction and Sexual Coercion?

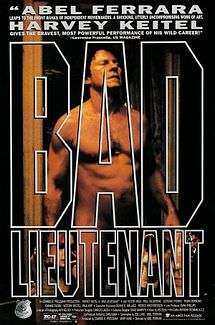

In a narrative that will have an image of Harvey Keitel's face hovering before your eyes as you read it, Tim Lynch of the Cato Institute's National Police Misconduct Reporting Project describes the crimes and subsequent punishment of Officer Julian Steele of Cincinnati, Ohio. As horrible and blatant as Steele's actions were, this story is actually happier than most such tales of law enforcement abuse of power, because it ends with Steele behind bars for a lengthy stay.

We pick up Lynch's story after a series of robberies yields a "clue" in the form of Alicia Maxton's license plate scribbed down by a concerned citizen:

Now Officer Julian Steele enters the picture. When he finds out Ms. Maxton has children, he goes to their school and arrests all three. To protect the identities of the minors, the Court only provides us with initials. One of the minors is RM. RM is driven to the police station where he is interrogated. Mom is not informed because Steele instructed the school people not to tell her what was happening to her children.

RM denies any involvement in the robberies. Steele tells this minor that if he does not confess, his mom will be jailed and she will lose custody of his siblings. Frightened, RM falsely confesses, and Officer Steele records the "confession" a second time. RM is then charged with the robberies and is imprisoned.

The next day, Steele tells the school that he does not really believe RM was involved in the robberies. Among other things, RM does not match the physical description of the suspect.

Keep in mind that R.M. is now in jail, even though Officer Steele has publicly admitted that he suspects the kid of nothing. So, is R.M. released? Not quite. According to the Ohio Supreme Court (PDF), which heard Steele's appeal of his convictions in the case:

Although R.M. did not fit the physical descriptions of the robbers, Steele took R.M. to the police station and interrogated him extensively, using threatening and coercive tactics, prior to any attempt to offer him his constitutionally guaranteed Miranda warning.

Let's go back to Lynch:

Over the next week, Steele arranges several meetings with Mom under the guise of discussing RM's case. One such meeting is at Steele's apartment and he tells Mom that he thinks he might be able to get RM out of detention because he can cut through all the damn red tape. And he wants to help out because he does not personally believe RM was involved. Then Steele changes the subject (or tries to anyway) to sex. Mom goes along with the overture because she believes Steele is the one who has the power to get her son's release.

That's actually a bit delicate. The court says, "During one of Alicia's visits to Steele's apartment, Steele asked her to engage in sexual activity with him. Alicia testified that she complied with Steele's requests because she believed that he had the power over R.M.'s release."

That's right, R.M. is cooling his heels in jail all this time, even though Steele, the arresting officer, suspects him of nothing other than, apparently, having a hot mom. From the Supreme Court of Ohio, again:

The prosecutor mistakenly assumed that R.M. had been sent home on the day of his arrest. When, on the ninth day, she discovered that R.M. was still in lock-up, she immediately had R.M. released and dismissed his charges.

Even for the U.S. criminal justice system in its current state, this appears to be a bit much. Steele gets called on the carpet, investigated, and subsequently charged with several crimes. He is ultimately convicted of abductng and intimidating R.M.

The case ended up before Ohio's Supreme Court because Steele appealed, claiming that abducting and intimidating is what cops do, so what's the problem?

To his credit, for the majority, Justice William M. O'Neill answered, with regard to intimidation, "there is no authority for the contention that police officers may use physical force, unlawful threats of harm, or a materially false or fraudulent writing with malice, bad faith, wantonness, or recklessness as part of a legitimate interrogation of a suspect."

With regard to the abduction charge, O'Neill wrote:

The facts underlying Steele's charge for abduction wereinextricably intertwined with those underlying the charges for intimidation. He took R.M. out of school in handcuffs, placed him in an interrogation room, and blatantly intimidated him with dire threats directed at his entire family, including his school-aged siblings. …

[T]here is nothing in the record to support the proposition that Steele had anything even approaching probable cause to arrest when he took this youngster out of school in handcuffs.

As a result, Steele is thankfully behind bars for five years, with five additional years of "community control."

Lynch predicts "[t]his case will become part of police training materials in the places where good training programs exist. It will also be taught in law school courses." He points out, though, that Maxton and her family are due some compensation for their ordeal, and that Steele may have left a trail of as-yet undiscovered victims.

If you don't want to read through the legal-ese of the court decision, there's a good official summary here.

If you're not yet following Tim Lynch at PoliceMisconduct.net, you should be.

Show Comments (90)