The Making of a Marijuana Majority

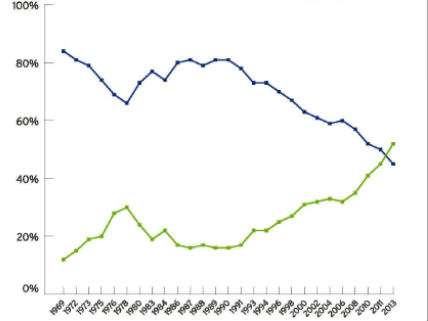

In a new Brookings Institution paper, William Galston and E.J. Dionne Jr. analyze data from the recent Pew Research Center survey finding majority support for marijuana legalization, along with several decades of Gallup Poll and General Social Survey results, to paint a picture of public opinion on this issue. The most striking development is a 20-point increase in support for legalization during the last decade or so, similar to the recent jump in support for gay marriage. I've argued that the same dynamic underlies both shifts: As people become more familar with formerly alien practices, they become more comfortable with them and less inclined to believe scary warnings about the consequences of greater tolerance. "Surveys have consistently shown that those who have a friend or relative who is gay or lesbian are far more sympathetic to gay rights than are those who do not," Galston and Dionne note. But they add that "individuals with a family member who smokes are no more likely to favor legalization than are those without such a relative." It is hard to tell what is going on there without additional information. But if people become aware of a relative's cannabis consumption because it is problematic and therefore conspicuous, you would not expect that experience to make them more supportive of legalization. More in line with the hypothesis that familiarity breeds tolerance, "whether someone has personally used marijuana is very important in shaping attitudes." Galston and Dionne elaborate: "Forty-eight percent of Americans say they have tried marijuana, up 10 points since 2003. Among those who have used marijuana, 70 percent support legalization; among those who have not, only 35 percent do." There is a chicken-and-egg problem here, since pre-existing attitudes could at least partly explain both the willingness to try marijuana and the inclination to favor legalization. Still, it is plausible that smoking pot and finding that the government's warnings about it don't hold up is an experience that powerfully shapes opinions on drug policy.

Other interesting survey findings reviewed by Galston and Dionne (some of which I've noted here before):

- Age is inversely associated with support for legalization. The most dramatic difference is between Americans under 30, nearly two-thirds of whom say marijuana should be legal, and Americans 65 and older, where the numbers are almost exactly reversed. Again, these differences in opinion correspond to differences in direct experience with marijuana.

- Parenthood does not necessarily reduce support for legalization. While "becoming parents appeared to have moved baby boomers toward a more conservative stance on legalization," Galston and Dionne write, "more recent findings suggest that parenthood may not be as strong a factor in determining one's position as previously thought." In this year's Pew survey, there was no difference in support for legalization between parents and nonparents.

- Women are less likely than men to have used marijuana (42 percent vs. 54 percent) and to favor legalization (48 percent vs. 57 percent).

- Republicans are almost as likely as Democrats to have used marijuana (43 percent vs. 47 percent) but substantially less likely to support legalization (37 percent vs. 59 percent).

- Despite their overall support for prohibition, most Republicans and most conservatives say the federal government should not try to impose that policy on states that are experimenting with legalization. Galston and Dionne observe that "the existence of this substantial 'states' rights gap' suggests that conservatives' expressed preference for state over federal decision-making is not, at least on this issue, mere rhetoric." The Reason-Rupe Public Opinion Survey has found a similar willingness to elevate federalist principle above anti-pot prejudice.

- Many people who support pot prohibition nevertheless agree that "government efforts to enforce marijuana laws cost more than they are worth." That opinion was held by 72 percent of the Pew respondents, compared to the 52 percent who supported legalization.

Citing 2008 polling data from California, Galson and Dionne argue that although more people support legalization than oppose it, the latter group feels more strongly about the issue. The problem for proponents of legalization, they suggest, is that "marijuana itself is not seen as a positive good." But as they note, alcohol prohibition was repealed not because everyone decided that drinking was "a positive good" or that it posed no dangers but because most people concluded that the costs of trying to suppress it outweighed the benefits. According to the Pew survey, nearly three-quarters of Americans already hold a similar view about marijuana prohibition.

Far be it from me, as the author of a book that defends the morality of drug use, to suggest that questions of right and wrong are irrelevant to marijuana policy. But the way the Pew survey frames the issue is odd: "Do you personally believe that smoking marijuana is morally acceptable, morally wrong, or is it not a moral issue?" Half of the respondents said smoking marijuana is "not a moral issue," while another 12 percent said it is "morally acceptable"; only 32 percent said it is "morally wrong." But the question is confusing, since a choice that raises no moral issue (the choice between a red and a blue tie, for instance) is morally acceptable by definition. Furthermore, while the respondents who said smoking pot is "morally wrong" presumably believe that is true in all circumstances, the same cannot be said of the other respondents, who might agree that smoking pot is morally unacceptable at work or behind the wheel. Similarly, while a minority of Americans may think that drinking is always wrong, most would say it depends on the context, as moral judgments often do.

The analogy with alcohol, which was emphasized by the successful legalization campaigns in Colorado and Washington, does not require believing that marijuana is utterly harmless. It simply requires recognizing that marijuana, like alcohol, can be consumed responsibly and that prohibition is not a wise, fair, or cost-effective way to discourage excess. "Although a majority believe that alcohol is more harmful to individuals and to society than is marijuana," Galston and Dionne write, "alcohol continues to enjoy much broader social acceptance." I suspect that gap will shrink during the next decade or two as today's anti-pot retirees die and the rest of us observe the results of the experiments in Colorado, Washington, and other states that follow their example.

Show Comments (3)