Nationalize Facebook? Really?

Idle minds are the devil's workshop

From the really, really, really awful ideas department, Philip Howard, currently a fellow at Princeton University's Center for Information Technology Policy, argues on Slate for nationalizing Facebook. The prospect ("thought experiment"), which Professor Howard admits at the end of his piece is "probably a nonstarter," is actually horrifying, even though the good professor argues "the benefits outweigh the risks." What benefits does he see to forcibly seizing the property of Mark Zuckerberg and everyone who's bought a share in the rapidly deteriorating stock of Facebook (precipitated even more, just yesterday, by it being the first day early investors could sell theirs)? To the text!:

Over the last several years, Facebook has become a public good and an important social resource. But as a company, it is behaving badly, and long term, that may cost it: A spring survey found that almost half of Americans believe that Facebook will eventually fade away. Even the business side has been a bit of a disaster lately, with earnings lower than expected and the news that a significant portion of Facebook profiles are fake. If neither users nor investors can be confident in the company, it's time we start discussing an idea that might seem crazy: nationalizing Facebook.

Of course, Facebook is not a public good, it's a publicly traded company (for less than three months) that may well be a social resource, but it is not a unique or particularly pioneering one. Much of the utility of Facebook comes from the self-organizing principle at work among its users. Internet kids know first there was Friendster ("but it was kinda lame!"), then MySpace, which briefly became a youth cultural icon and was acquired by News Corp before losing out to Facebook in the social networking wars of the aughts. MySpace is a "social site" now, and focused on music and entertainment. Friendster (still around!) turned into a "social site" too, and decided to focus on gaming. It's big in Asia. And of course Google entered the foray of the social networking wars when Facebook looked it had one them. Of course there's Twitter, too, but that's become something completely different than Facebook.

Those are important observations for the thought experiment. Facebook is not an institution, it's a corporation (they're people, too!) that provides a tool, social networking, which is arguably a cultural institution, at least enough of one for a movie. Unlike the nationalization targets of past and present, like energy companies, utilities or banks, the company Facebook doesn't have a physical (or digital, even) infrastructure that can be seized and made into an exclusive provider. When the government seizes roads or utilities, you largely still have to use those. The entire infrastructure can be taken by the government, and competition becomes prohibitively expensive or even impossible. I can't imagine a thought experiment that could lock users into their Facebook account. Nationalization would be the biggest boon to Google Plus, so perhaps the next step would be to nationalize Google too.

Yet Professor Howard actually argues that "[w]ith 80 percent of market share, Facebook is already a monopoly, and being publicly traded hasn't made it more socially responsible. The map of its global market dominanceis impressive, though some might say this is a map of colonization." This is what happens when the professors figure out what the kids are doing. Yet when you dig in to what this means (users!), Howard appears to be half-right but mostly wrong. Facebook appears to have actually lost 400,000 users in North America in the year ending March 31. The chart of the geographical breakdown of Facebook users shows its greatest growth in the 2011 was in users in South America, about 62 percent, Asia (48 percent) and Africa (47 percent). Which is exactly like colonization, except it's not. The users in South America, Asia and Africa are, presumably, South Americans, Asians and Africans. Internet penetration rates on those continents right now are, respectively, 40 percent, 26 percent and 16 percent, meaning as those rates increase Facebook is bound to meet local competitors who may be better poised to give local internet users the kind of social network they want. About 18 percent of internet users in Asia and 27 percent in Africa have Facebook accounts. There are of course, plenty of zombie Facebook accounts, so those are actually the upper limit of what the actual penetration of Facebook is among internet users in those places.

The phenomenon of social networking and Facebook is a product of the free-for-all that is the Internet. Websites and social networks live and die by their popularity among users; the Internet, two decades on, remains a rapidly changing environment, and the idea that Facebook's present dominance is a gauge of its future does not bear out. Take the movement of its stock price since its IPO earlier this year. Though Howard mentions it primarily to paint Facebook as a company in need of some government intervention, the deteriorating stock price is actually a signal that the marketplace (everybody buying and selling shares) does not have confidence in Facebook's and its boosters' evaluations (which are, naturally, ever cheery). By the survey Howard points to, half of Americans agree. And of course the market will know better, because its constituents have got skin in the game.

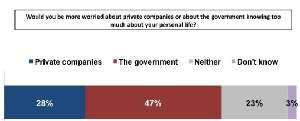

As to the actual benefits Howard lists, there's no evidence the government would be a good steward of Facebook users' privacy. Americans' privacy is under nearly constant assault by government. The government faces serious data breaches at an increasing pace. Government officials are known to play fast and loose with the rules for personal and political gain. Governments tout transparency and accountability but regularly flout both. Perhaps more tellingly, 47 percent of Americans are more worried about their government knowing too much about their personal lives, with only 28 percent distrusting private companies more.

Whatever privacy sins Facebook may be committing, there are clear accountability measures. People may complain about privacy settings on Facebook (more seem to complain about the timeline, at least on my feed), but ultimately Facebook users are free to move on to other social networking sites or to use social networking tools differently. If there is a deficiency in Facebook that can be corrected by another social network, competitors will arise. Google has already tried to help its users along into Google Plus by integrating its various internet properties, like YouTube and Gmail. So long as Facebook and Google and everyone else providing a service on the Internet is allowed to attempt to react to market forces, they'll be able to adapt and evolve, without an intelligent designer from government. The Internet is a complex and adaptive system, like all human activity, and intervention by government, because it is by definition a centralizing force, restricts activity and thus the dynamism of the system.

Once the government nationalizes something, it becomes, by definition, too big to fail. When Richard Nixon created what became Amtrak, he meant to intervene to save a dying passenger rail industry. More than forty years later, Amtrak operates at a constant loss, with virtually no competition to discipline it. For the Internet to continue to provide an environment for human creativity and the entrepreneurial spirit, companies like Facebook and Google have to be able to succeed without the threat of government intervention most importantly so that they can fail without it as well. The Internet is the closest thing we have to a free market, to the self-organizing principle at work, on this planet—something better is always bound to come along there, so long as the government doesn't intervene.

There are plenty more risks to outweigh whatever limited benefits to nationalizing Facebook there might be--add your own in the comments!

Show Comments (73)