Have the Feds Given 'Tacit Approval' to Marijuana Legalization?

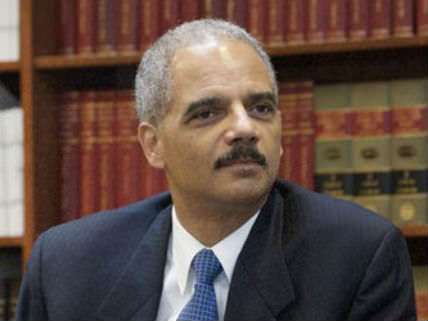

It has been nearly 10 months since voters in Colorado and Washington decided to legalize marijuana, and the Obama administration still has not said anything substantive in response, despite Attorney General Eric Holder's repeated promises that a policy will be announced "soon." Does this long silence amount to "tacit approval," as a Colorado legislator who co-sponsored laws aimed at taxing and regulating marijuana recently claimed in an interview with TPM? An unnamed Colorado official who has been involved in discussions with the Justice Department concurred. "They're well aware of what we've been up to," he said. "I do think that it's fair to say that we have their tacit approval at this point." The department has been kept apprised of the implementation process, the official noted, and so far no one has said to stop. Washington officials were more cautious. "They've not indicated that they're going to try to stop us," a spokesman for Gov. Jay Inslee said. "We're operating as if this is is a go, and we haven't been told otherwise."

Yet both Holder and President Obama have carefully avoided offering any assurances with regard to commercial production and distribution of marijuana, which is scheduled to begin early next year in both states. "We've got bigger fish to fry," Obama told ABC News last December. "It would not make sense for us to see a top priority as going after recreational users in states that have determined that it's legal." But that comment did not signal any change in policy, since "going after recreational users" has never been "a top priority" for the feds, who eschew penny-ante marijuana cases. The real question, as I said at the time, is whether the administration is willing to tolerate state-licensed pot growers and retailers.

There is still plenty of time to say no. The Justice Department could wait until the stores start opening, then send letters to the operators and their landlords, threatening them with forfeiture and prosecution. That method, which requires no actual raids or arrests, proved quite effective for John Walsh, the U.S. attorney for Colorado, when he decided that 50 or so medical marijuana dispensaries were too close to schools. At the same time, Walsh left hundreds of other dispensaries unmolested, and these are the businesses that will start serving the recreational market in January. Which raises the question: Did Walsh run out of envelopes? Having discovered a virtually free way to shut down dispensaries, why did he let the vast majority of them continue operating? And if those businesses are tolerable, will it make a crucial difference when they stop asking their customers for doctors' notes?

Another possible strategy for blocking marijuana legalization is a lawsuit claiming that it violates the Supremacy Clause because it conflicts with federal law. But while TPM claims "the state laws directly contradict the federal Controlled Substances Act," that is not actually true, at least insofar as the laws specify the circumstances in which people can avoid state penalties for production, possession, or sale of marijuana. The Supreme Court, based on an absurdly broad reading of the power to regulate interstate commmerce, has said the federal government can continue to enforce its ban on marijuana even in states that allow medical use of the plant. But that does not mean the feds can force state officials to help them, let alone compel state legislators to enact their own ban. Under our federal system, states have no obligation to forbid everything Congress decides to treat as a crime.

To prevail with a Supremacy Clause claim, the Justice Department would have to show a "positive conflict" with the Controlled Substances Act, which does not exist merely because states decline to punish actions that remain illegal under the federal statute. The difficulty of making such a claim stick helps explain why the Justice Department has never deployed it against state medical marijuana laws, the first of which was enacted 17 years ago. Holder could nevertheless file a lawsuit as a delaying tactic, and he has at least four more months to do that before state-licensed pot stores are open for business.

Show Comments (49)