The Prohibitionist Curse

Success softened drug warriors' arguments. Now failure has exposed them.

Economists specializing in international development have identified what they call the "resource curse": Contrary to expectations, an abundance of lucrative natural resources is often associated with poor economic performance. Although you'd think that sitting on trillions of gallons of oil would make your country richer, overreliance on a single sector tends to blunt development in others while inviting both corruption and laziness from those who control the taps. If a ruling class can safely siphon off profits from a guaranteed moneymaker, what incentive is there to liberalize or otherwise ignite broad-based prosperity?

Resource-free countries such as Japan, Switzerland, and Singapore get rich by relying on trade and brain work instead of brute extraction, while resource-swollen countries such as Saudi Arabia, Russia, and Venezuela remain poor, corrupt, and illiberal. Having a built-in advantage can become a hindrance if, to paraphrase Jim Hightower's crack about George H.W. Bush at the 1988 Democratic National Convention, you're born on third base thinking you hit a triple. Those who have to hustle for their supper tend to be more industrious and creative; those who don't will coast for as long as they can get away with it.

There are exceptions to this tendency. The United States, Canada, and Australia haven't let natural resources prevent them from getting rich. Nor have Cambodia and Bangladesh benefited noticeably from their comparative dearth. But as the decline of newspaper companies, the humbling of sports dynasties, and the demise of onetime monopolies such as Kodak illustrate, success can mask deep flaws and smother any urgency to fix them. When the conditions fueling success change quickly-when technology creates a better delivery system for a popular activity, or when the price of oil plummets-the battered incumbents can suddenly look ridiculous, anachronistic, and bankrupt.

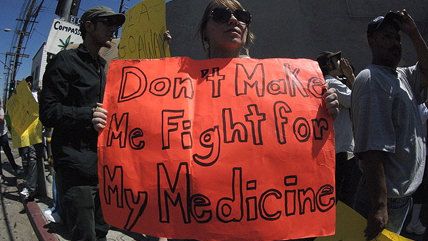

The same goes for political commentators, as the opening of recreational marijuana stores in Colorado last January laid bare for all to see. The dead-enders still clamoring for prohibition in a country quickly leaving them behind demonstrated the intellectual rot caused by being on the winning side too long.

On January 3, two days after Colorado's state-licensed pot shops opened their doors, New York Times columnist and "national greatness" authoritarian David Brooks published a piece that, after detailing his own youthful pot smoking, pivoted to an explanation of why making such transgressions punishable by life-ruining encounters with the criminal justice system is good for the moral fabric of society. "We now have a couple states-Colorado and Washington -that have gone into the business of effectively encouraging drug use," Brooks wrote. That sentence was precisely as accurate as a mocking response from Gawker's John Cook: "We now have a couple states that have gone into the business of effectively encouraging David Brooks."

Brooks continued: "Laws profoundly mold culture, so what sort of community do we want our laws to nurture? What sort of individuals and behaviors do our governments want to encourage? I'd say that in healthy societies government wants to subtly tip the scale to favor temperate, prudent, self-governing citizenship. In those societies, government subtly encourages the highest pleasures, like enjoying the arts or being in nature, and discourages lesser pleasures, like being stoned."

There is nothing at all subtle about the way our government "tip[s] the scale" against "lesser pleasures." The encouragement that Brooks favors involves stripping people of their dignity and liberty for doing what Brooks used to do. It requires imprisoning people who assist that activity by supplying the dried vegetable matter that Brooks once enjoyed but now abjures. Such "nurturing" is part of a historically unprecedented mass incarceration system that disproportionately targets poor minorities while creating a black market that generates murderous violence and other culture-degrading pathologies.

While Brooks ignored the brutal human cost of criminalizing the ingestion of disfavored substances, Fox News host Bill O'Reilly denied that such criminal penalties even exist. On January 6, O'Reilly-the most-watched cable news personality for a decade running-claimed "there's no mass arrests of [marijuana] users," who instead "get a ticket." As Senior Editor Jacob Sullum retorted the next day at reason.com, "According to the FBI, police in the United States made about 750,000 marijuana arrests in 2012, the vast majority (87 percent) for simple possession.…From 1996 through 2012, there were more than 12 million marijuana arrests.…More than 11 million of the pot busts involved simple possession."

Journalists who should know better repeat such ignorance if it bolsters their case for prohibition. "No one gets prison for just smoking pot," tweeted Washington Times editorialist Emily Miller on January 9. That would be news to, among others, Chris Diaz, currently serving a three-year prison sentence in Texas for possessing half an ounce of medical marijuana.

Sillier still, on January 2 Washington Post columnist Ruth Marcus coupled her admission of youthful weed enjoyment with this non sequitur: "The reason to single out marijuana is the simple fact of its current (semi-)illegality." Pot is "less addictive" than alcohol and tobacco, Marcus writes, and "an occasional joint" is "no worse than an occasional drink," but it needs to stay illegal because it's illegal.

The once prestigious editor Tina Brown topped that nonsense with this January 3 tweet: "Legal weed contributes to us being a fatter, dumber, sleepier nation even less able to compete with the Chinese."

As Sullum pointed out in a January 8 syndicated column, "Colorado's path-breaking legalization of the marijuana business has revealed the intellectual bankruptcy of people who think violence is an appropriate response to consumption of psychoactive substances they do not like.…They do not even seem to understand that a moral justification is needed for using force to suppress an activity that violates no one's rights."

This is good news for those of us-now a majority of Americans, according to several recent polls-who think marijuana prohibition should be repealed. Tina Brown, David Brooks, and Ruth Marcus, who were pretty lonely in their legalization laments, were greeted by hoots of derision. That response represents an interesting reversal.

For decades, all the way up to November 2010, prohibitionists could rely on dismissive giggling and hand waving any time the rest of us advocated legalizing drugs. And those current or former pot smokers in or near power who should have known better were often the ones leading the mockery. When California tried crossing over from medical marijuana to full legalization in 2010 through Proposition 19, the state's editorial boards almost universally panned the measure. Instead of fact-based persuasion, they offered "reefer madness" and "what were they smoking?" jokes. Then-Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger warned, tellingly and inaccurately, that legalization would make "California a laughingstock."

This is how prohibitionists and cowards alike avoided having an argument: by playing to the insecurity of political elites who were desperate to be taken seriously. Advocates for realigning marijuana laws toward reality and human decency were treated like Tommy Chong at a church picnic. Even the Democratic Party, whose members are more inclined than the general public to favor legalization, used such mockery to marginalize opponents of the war on drugs. When people asked President Barack Obama about pot legalization during his first term, he generally responded with a laugh or a dismissive joke.

Success in Colorado (and Washington state and Uruguay, both of which also legalized pot recently) will soon make such tactics untenable. There is a lesson here for anyone making political arguments: If you side with power and prevailing policy on a given issue, it will not suffice to point and laugh at those crazy enough to challenge the status quo. Where ideas atrophy, politics will eventually follow.

Show Comments (48)