The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Freedom Fighters

What coins and papyri tell us about the ideals of ancient Jewish rebels.

Historians of the ancient world depend on the writings of elite historians like Thucydides, Livy, and Josephus, but they consult other sources as well, especially the evidence of material culture. Archaeologists have unearthed cities, fortresses, roads, aqueducts, bridges, pottery, jewelry, sculpture, frescoes, and the minutiae of everyday life. They have also found writing, most often inscribed on stone or written in ink on papyri which were preserved by dry conditions in the desert.

They have also discovered coins, gold, silver and bronze, which are of no small value to scholars. Coins provide the message that the people who issued them wanted to convey. We can read that message in both the images on the coins and the legends (writing). For example, one of the most famous coins of the ancient world reads "Ides of March" and it displays two daggers and the cap of a freed slave. Unmistakably, it advertises the assassination of Julius Caesar, the most famous assassination in history.

The Jewish rebels of both the Great Revolt (66-70 CE) and the Bar Kokhba Revolt (132-136 CE) also issued coins. They open a window into the goals and ideals of the rebels. Robert Silverman offers an accessible and perceptive discussion of these coins in two recent articles here and here.

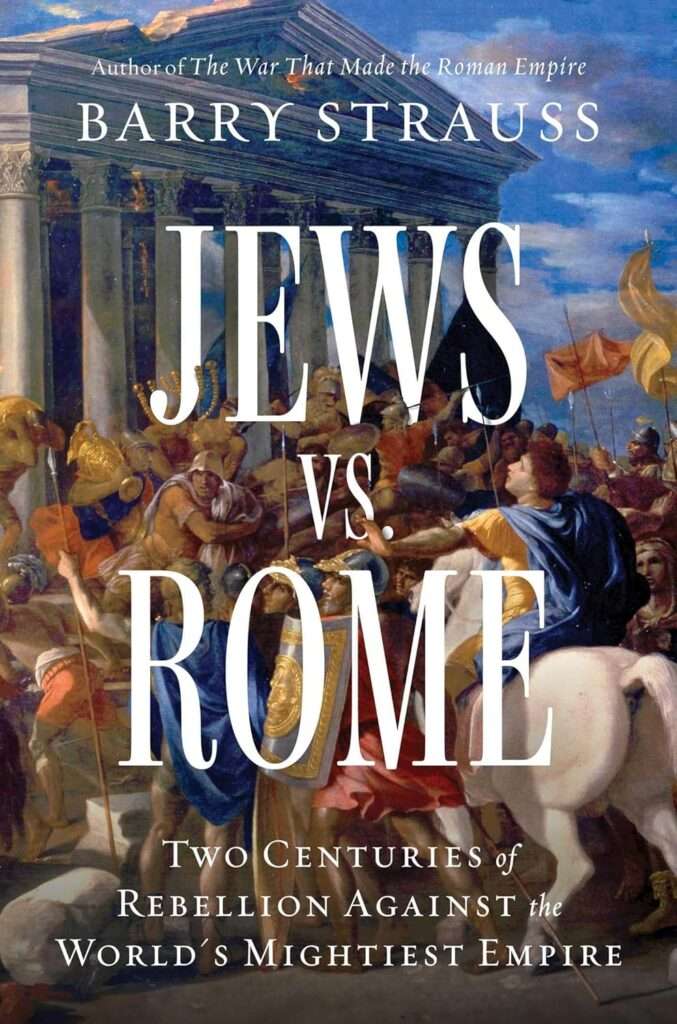

I discuss the coins of the Great Revolt as well as other related documents in this excerpt from my new book, Jews vs. Rome: Two Centuries of Rebellion Against the World's Mightiest Empire (Simon & Schuster, 2025):

The rebels of 66 believed that they were building a government and they thought it would last. The coins they struck testify to their hopes and beliefs. During the five years of the rebellion (66-70), they issued both silver and bronze coins. The coins were notably precise, professional, and pure, with an impressive silver content of 98 per cent, making them purer than Nero's silver coins. More important, they were the first, and perhaps the only true rebel coinage ever issued in the Roman Empire. From Augustus on, only the emperor had the right to mint silver (or gold) coins. The Jewish silver coins marked a real break. They were a clear declaration of independence….

The coins have occasioned many scholarly debates about who produced them, where, and what their legends and symbolism mean. Arguably, the silver coins were minted by the priesthood, who controlled the Temple and its treasure. Likewise, the bronze coins were arguably minted by more radical groups who dominated Jerusalem beginning in 68.

Whoever produced them, all the coins avow independence from Rome. They also proclaim Jewish nationhood: they are coins of Israel. They are not secular. Few, if any coins of ancient states were secular. Greek and Roman coins refer to their various pagan deities. Jews do not depict God, of course, since that was prohibited by the Ten Commandments. But the various symbols used on these coins and the references to Zion and to the holiness of Jerusalem make the religious character of the rebels' program unmistakable. It was a program to appeal to Zealots, who wanted their country to be a Jewish state, ruled from the House of God in Jerusalem, rather than a pagan state ruled from the House of Augustus in Caesarea. The reference to freedom surely also appealed to the sicarii ["dagger men," among the most determined of Rome's enemies] who had long emphasized freedom, although they were driven out of Jerusalem early in the revolt. In fact, the famous sicarii remained largely offstage until the final act of the drama at Masada, eight years later.

The rebels were freedom fighters. The coins offer the most eloquent but not the only testimony of this. Josephus, for example, states repeatedly that freedom was their primary goal. He wrote in Greek and uses the Greek word for freedom (eleutheria), but the coins, inscribed in Hebrew, use the Hebrew term: herut.

Freedom (herut) had a specific meaning in the ancient Jewish context. It meant liberation from slavery, debt, and exile as well as repatriation to one's homeland, where a person could worship God in His Temple. It had both positive (freedom to) and negative (freedom from) connotations, but it differed from the Athenian notion of freedom as participating in politics—literally, the affairs of the polis, or city-state—and "living as you please." Jewish freedom meant subordination to God's law. The new Jewish state would be a temple state, not a civic state. And it would govern itself. Redemption (geulah) connotes the nation's hope that God would deliver Israel from its tribulations and restore it so that Jews could live in the land safely, in obedience to the divine law and protected by an eternal covenant. Redemption surely had a messianic connotation to many Jews.

It wasn't only the minters of rebel coins who cited "freedom" and "redemption." People doing ordinary business used the terms as well. The words "freedom" and "redemption" appear on six papyrus documents from the era of the Great Revolt. They were found in caves in the Judean Desert, where they were probably brought by refugees from Jerusalem or Masada. They are legal documents having to do with buying and selling, land access, or divorce. They all use the dating of the new state of Israel. Three of the documents are in Aramaic, but the other three are in Hebrew, a clear statement of support for the revolt because Hebrew was not otherwise used in legal texts.

Show Comments (9)