The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Did Glossip and the Oklahoma Attorney General Collusively Conceal Evidence to Win Their U.S. Supreme Court Case?

Justice Thomas observes in his dissent that "the parties collusively excluded" evidence—which I presented to the Court for the victim's family—"in order to reach a predetermined outcome." And the Court majority offers no defense of this deceitful maneuver.

Today the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in favor of death row inmate Richard Glossip. By a 5-3 majority, the Court found that the prosecutors in the case "knowingly" failed to correct false testimony from an important state witness at Glossip's murder trial. But in reaching this conclusion, the majority refused to consider highly relevant evidence that I presented for the victim's family disproving this finding. The majority concluded that my evidence constituted "extra-record materials not properly before the Court." But as Justice Thomas pointed out in his powerful dissenting opinion, the parties in the case (Glossip and the Oklahoma Attorney General's Office) "collusively excluded this highly relevant evidence" from the record. The parties' dubious maneuver raises serious questions about the justice of today's ruling—and about our nation's treatment of crime victims' families.

VC readers will recall that I blogged about this case earlier, explaining the story behind how death row inmate Glossip concocted a phantom "Brady violation" and got Supreme Court review. See Part I, Part II, and Part III.) To quickly summarize, Glossip was convicted of the 1997 murder of Barry Van Treese in 1998. After a reversal for ineffective assistance of counsel, Glossip was convicted again in 2004. The main state witness was Justin Sneed, who confessed that he (Sneed) had murdered Van Treese after Glossip had commissioned the murder.

In 2007, the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals ("OCCA") affirmed Glossip's conviction and sentence, rejecting Glossip's claim that the evidence proved only that he was an accessory-after-the-fact. In the years since, courts have rejected multiple challenges by Glossip to his conviction and death sentence.

Nearly two decades later, Oklahoma was preparing to execute Glossip when a new Attorney General, Gentner Drummond, was elected. Shortly after assuming office in January 2023, and apparently sensing political opportunity, the new Attorney General hastily commissioned an "independent" review of Glossip's conviction. Conveniently, General Drummond hired Rex Duncan, his lifelong friend and a political supporter who possessed limited experience in capital litigation. Duncan suddenly discovered "new" evidence the prosecution had purportedly concealed from the defense.

As the tale was told in Glossip's and Oklahoma's briefs before the Oklahoma courts and, ultimately, the Supreme Court, the trial prosecutors concealed from Glossip's defense team information about Sneed's lithium usage and related psychiatric care. This story rested on an interpretation of notes the prosecutors took during a pretrial interview of Sneed. Specifically, General Drummond asserted that the handwritten notes indicated that Sneed told the prosecutors "that he was 'on lithium' not by mistake, but in connection with a 'Dr. Trumpet.'"

The OCCA rejected the argument and, after relisting the case twelve times, the Supreme Court granted cert. I filed a motion to participate in oral argument for the family. But, instead, the Court appointed an amicus to argue for affirming the judgment below.

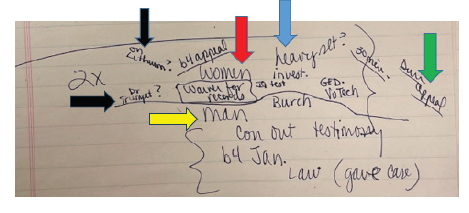

I filed an amicus brief in the case, explaining that the prosecutors' handwritten notes did not somehow reveal that prosecutors knew about Sneed's alleged lithium prescription and usage, but rather merely showed the prosecutors were recording Sneed recounting what Glossip's defense attorney's were asking about. Specifically, I explained that the notes from one of the prosecutors contained question marks—as shown by the references marked with the black arrows below:

Stepping back to examine the surrounding context of these two notes clarifies that the prosecutor was simply recording Sneed recounting what Glossip's defense team was questioning him (Sneed) about—hence, the two question marks reflecting questions being asked. The prosecutor's adjoining notes reflect two visits ("2X") by defense representatives—with notes about the two visits separated by a curving line.

Turning to the first visit, as shown by the note flagged with a red arrow above, Sneed's visitors were "women." As shown by the notes flagged with a blue arrow, that visit involved an investigator ("invest.") who may have been heavy set ("heavy set?"). As shown by the notes flagged by the green arrow, the defense representatives may have been involved in Glossip's earlier direct "appeal." And, finally, as shown by the notes flagged by the two black arrows, the women questioned Sneed about (1) whether he was "on lithium?" and (2) a "Dr[.] Trumpet?"—i.e., questioned by the women representing Glossip. Thus, read in context, the key words in the prosecutor's notes reveal that Sneed was recounting not what the prosecutor had independently learned (much less confirmed and knew) but rather questions Glossip's defense team was asking Sneed.

During oral argument in October, Glossip and the Oklahoma Attorney General both argued for setting Glossip's murder conviction aside. Today, the Supreme Court agreed, finding that the OCCA had misinterpreted federal law. The Court held that the Oklahoma courts had misinterpreted Napue v. Illinois, which became an underpinning for the Brady rule and explained that due process forbids prosecutors from "the knowing use of false evidence." But then today's opinion continues to make new factual findings the case for the first time on appeal. Very surprisingly, the Court held that remedy was not the standard remand for further proceedings but rather an automatic new trial for Glossip. The Court got it wrong—or, even more clearly, the Court ruled based on distorted record where the parties collusively concealed important information.

In the majority opinion, Justice Sotomayor specifically discussed the issues raised by my interpretation of the prosecutor's notes:

In an amicus brief, the Van Treese family argues that it was Glossip's counsel who asked Sneed about his lithium prescription, and that [the prosecutor's] notes reveal only that Sneed relayed those questions to [the prosecutor]. See Brief for Victim Family Members as Amici Curiae 7–22. That argument relies heavily on extra-record materials not properly before the Court, including a recent unsworn statement from [the prosecutor] adopting the family's interpretation of the notes. (The dissent, which criticizes the independent counsel for "impugning" the trial prosecutors' reputation, post, at 15, justifies its reliance on these materials by accusing the Oklahoma attorney general of "collusively exclud[ing]" them from the record, see post, at 42.) Nor would accepting the family's account change the Napue analysis. Whatever the impetus for the conversation, the family agrees that Sneed and [the prosecutor] discussed Dr. Trombka and lithium. The natural inference is that Sneed explained to [the prosecutor] the circumstances that led to his lithium use.

Several observations on this passage. First, and most notably, Justice Sotomayor merely flagged the dissent's position accusing the Oklahoma attorney general of "collusively exclud[ing] … highly relevant evidence from the record." Justice Sotomayor did not dispute that characterization's accuracy.

Second, Justice Sotomayor concluded that the materials I provided from the family would not "change" the Napue analysis, based on what she believes is the "natural inference" about a "conversation" that then ensued between the prosecutors and the witness (a conversation that is not memorialized in the prosecutor's notes).

This is a gobsmackingly inaccurate description of the materials that I presented. As recounted in a letter from both prosecutors in the case attached to my brief, what happened during the Sneed interview was that he recounted that Glossip's defense attorneys "asked him questions about lithium and Dr. Trumpet. The question marks after those two words indicate that the women asked him those questions." Van Treese Br. at 10a (reprinting letter from prosecutors). Contrary to the alleged "natural inference" from the notes, the notes' authors explain that Sneed was no discussing the "circumstances" surrounding Sneed's prescribed use of lithium—only the fact that the defense attorneys were asking about it.

Justice Sotomayor tried to support her "natural inference" with a reference to a jail medical record, which appeared to include information about Sneed's lithium prescription. But, as noted above, for prosecutors to violate Napue, they must "knowingly" use false evidence. Even assuming that the prison medical record showed that Sneed was prescribed lithium, that record did not show prosecutors "knowingly" used false testimony to the contrary. As the two prosecutors explained in a letter included in my brief to the court: "The two of us, in a combined over fifty-five years of prosecuting cases, have never seen a transport order like this document. The first time we saw this specific document was when it was attached to a defense filing in 2022," which (of course) was nearly two decades after Glossip's trial. The prosecutors could not have knowingly used testimony contrary to a record that they had never seen.

Justice Sotomayor also noted that Justice Thomas' dissent argued for a remand to the Oklahoma courts to provide "the Van Treese family [with] the opportunity to present its case." But, for Justice Sotomayor, this was not enough because "[t]he family has not requested an evidentiary hearing (or participation in one) at any stage before the OCCA and does not request that relief before this Court." (Op. at 27 n.11.) Her conclusion is obviously disappointing, particularly given that I filed a motion to participate in oral argument before the Court—a motion that the Court denied (without explanation) in favor of instead giving a Court-appointed amicus the opportunity to defend the judgment below. Moreover, the family's brief obviously asked the Court to simply affirm the judgment below. Once the Supreme Court rejected the family's overarching position, the family would clearly have preferred to have their factual arguments considered by the Oklahoma courts—rather than simply ignored as "extra-record" by the Supreme Court in its haste to command a new state court trial.

Justice Thomas' dissent (joined in full by Justice Alito and in part by Justice Barrett) highlighted numerous flaws in the majority's opinion. In this post, I will spotlight Justice Thomas' important discussion of my amicus brief for the victim's family. Justice Thomas explains how my brief advanced a perfectly plausible alternative reading of the notes in question:

Concluding that no new factual development is needed is particularly inappropriate given the alternative reading of the notes advanced by the Van Treese family in this Court. As discussed above, the family has argued that the supposed "smoking gun"—the notes from Box 8—in fact reflects Sneed's recollection of what defense counsel had asked him at two prior meetings. [Prosecutors] Smothermon and Ackley have likewise endorsed this interpretation, which casts serious doubt on Glossip's and the State's theory. If Sneed simply reported that he was asked about Dr. Trombka without admitting Dr. Trombka prescribed him lithium, Smothermon and Ackley would have had no reason to know that Dr. Trombka prescribed him lithium. And, the indication in Ackley's notes that Sneed apparently mentioned his "'tooth'" being "'pulled'" suggests that Sneed stood by his earlier story that he was mistakenly prescribed lithium when his tooth was pulled. (citations omitted).

For Justice Thomas, instead of the Supreme Court engaging in appellate fact-finding on a distorted record, the proper result would have been to send the case back to the Oklahoma courts for further consideration. Justice Thomas highlighted the "collusive" distortion of the record that the parties orchestrated in this case:

To the extent the Court insists it cannot endorse the family's theory because it relies on "extra-record materials not properly before the Court," ante, at 25, … that is because the parties collusively excluded this highly relevant evidence from the record in order to reach a predetermined outcome. The majority rewards this gamesmanship, and in so doing denies the victim's family the opportunity to present contrary evidence. (Dissent at 42 (emphasis added)).

Justice Thomas observed that the victim's family deserved its "day in court":

The "Government should turn square corners in dealing with the people." That command extends not only to criminal defendants, but also to their victims. "[C]onducting retrials years later inflicts substantial pain on crime victims," who must "relive their trauma and testify again," in this case 28 "years after the crim[e] occurred." The Oklahoma Constitution recognizes this interest by giving crime victims like the Van Treese family the right—"which shall be protected by law in a manner no less vigorous than the rights afforded to the accused"—"to be heard in any proceeding involving release, plea, sentencing, disposition, parole and any proceeding during which a right of the victim is implicated." Art. II, §34(A). Glossip, on the other hand, would suffer no prejudice from an evidentiary hearing in which the Van Treese family had the opportunity to present its case. If the evidence is as decisive as the majority believes, Glossip would still receive a new trial. There is no excuse for denying the Van Treese family its day in court. (citations omitted).

Justice Thomas decried how unfair it is for the Court to decide this case based on a collusively crafted and distorted set of facts:

After having bent the law at every turn to grant relief to Glossip, the Court suddenly retreats to faux formalism when dealing with the victim's family. The Court concludes that it need not honor the family's right to be heard because the family did not request an evidentiary hearing earlier in the proceedings. But, the family had no need to do so, since Glossip had conceded that "a hearing is necessary" for his claim to rise above the level of "speculation." And, before this Court, the Van Treese family has vigorously asserted its interests. The family filed the only brief opposing certiorari in this case. It filed a merits brief highlighting critical evidence that the parties sought to sweep under the rug. And, it filed a motion to participate in oral argument, which this Court denied. The majority's assertion that the family has sat on its rights is groundless. (Dissent at 43 (citations omitted).

Justice Thomas concluded his powerful dissent by chastising the majority for failing to consider the victim's family's interests: "[E]ven if the family had no formal right to be heard, any reasonable factfinder plainly could consider the account of the evidence that the family has brought to light, making the majority's procedural objections beside the point. Make no mistake: The majority is choosing to cast aside the family's interests. I would not."

In the back-and-forth between the majority and Justice Thomas, it will not be lost on the reader that the majority has no response to his observation that the parties (i.e., Glossip and the Oklahoma Attorney General) have "collusively excluded this highly relevant evidence from the record [about what the prosecutor's notes mean] in order to reach a predetermined outcome." As a result, for those who would cite this case as an example of trial prosecutors knowingly relying on false evidence, the case more accurately stands for the proposition that the Oklahoma Attorney General's Office and the defendant have succeeded, through "gamesmanship," in collusively distorting the record.

Commenting in a press release today on the "victory" he had obtained before the U.S. Supreme Court, Attorney General Drummond asserted that "[o]ur justice system is greatly diminished when an individual is convicted without a fair trial, but today we can celebrate that a great injustice has been swept away. I am pleased the high court has validated my grave concerns with how this prosecution was handled, and I am thankful we now have a fresh opportunity to see that justice is done."

From what I can see, General Drummond still has no explanation for why he "collusively excluded … highly relevant evidence from the record" to obtain his victory. Sadly, while the Attorney General is crowing about "justice being done," the victim's family may well be left with no remedy for his deceitful maneuver. It's a sad day for justice in this country when an attorney general can exclude highly relevant evidence and then win his case on a distorted record—leaving the victim's family to wonder why relevant facts about a murder trial held more than two decades ago can deceptively be swept under the rug.

One final note: The Court has sent the case back for a retrial. The evidence in this case is overwhelming. The family remains confident that when that new trial is held, the jury will return the same verdict as in the first two trials: guilty of first degree murder.

Update: For more legal analysis critical of today's ruling, see Kent Scheidegger's post here.

Correction: In my original post, I inaccurately described the Napue case as an "interpretation" of the Brady rule. As an alert reader (SMP0328) correctly points out, Brady was a later (and broader) decision, applying the same principles. I have corrected the post to reflect the timing.

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

The parties certainly overstated the strength of their evidence to a remarkable degree. Given the importance of the case and the unusual procedural posture, I don’t necessarily object to Barrett’s proposal to remand for more evidence, but it’s disappointing that five justices let themselves get snowed.

I think Barrett's was the best of the three opinions. She would have vacated the decision below, so that this very confusing record could be cleaned up. Unfortunately, she was alone. Each of the other participating Justices (Alito was recused), thought either the prosecutor was corrupt (the Sotomayor majority) or that those representing Richard Glossip were (Thomas dissent).

From the opinion: “GORSUCH, J., took no part in the consideration or decision of the case.”

Presumably because of prior involvement when he was on the 10th Cir.

Gorsuch was recused. Alito joined Thomas’s opinion.

D'oh! Thanks for the correction.

I have similar impression. The facts appear to be very much disputed. Reading the handwritten notes , its very difficult to ascertain with any confidence what each party actually knew. I am with Barrett to remand for clearing up the record. fwiw, I am not agreeing or disagreeing with P Cassell. I am presuming he has had discussions with th members of the original prosecution and thus has better insight into the facts.

Lawless decision from a weak court. Roberts is so concerned with the court's public support that we have cases like this. It's disgusting.

This is a prosecutor's biased opinion loaded with adjectives whose only purpose is to jerk tears.

The basic case relies on a jailhouse snitch trading his own death penalty for a life sentence. That's not beyond a reasonable doubt. Everything else is political grandstanding meant to make people forget the jailhouse snitch.

I have no idea of he's guilty or not, or of what. But I do know it's not beyond a reasonable doubt.

24 people that heard all the evidence, the snitch and everything else, decided he was guilty. I guess we're going for 36.

Juries aren't perfect. There are enough examples of juries convicting on atrocious evidence and jailhouse snitches for you to know better.

This isn't a jailhouse snitch, someone who just met Glossip in the cell. This was a co-conspirator in the crime.

He got a deal. That should factor into his credibility. Juries weigh credibility all the time.

Two juries thought he was credible enough together with all the other evidence to convict.

Two juries thought he was credible enough together with all the other evidence to convict.

Alternatively, two juries did not think he was too unbelievable to acquit,

The Court held that the Oklahoma courts had misinterpreted Napue v. Illinois, which interpreted the Brady rule

Napue was decided in 1959, Brady was decided in 1963.

Thank you for the correction. I've corrected the post, with acknowledgment of your point, to reflect the correct sequence here.

dude, you need lithium.

"extra-record materials not properly before the Court."

Is this not an important rule?

Listening to Cassell during his appearance on the 'We the People' podcast, he sidesteps this question a dozen or more times, and seems to be of the opinion that there is some sort of burden to refute his extra-record argument anyway.

It's an important rule but also can be abused if the supposedly adversarial parties are working together to limit the record. The rule relies on each side working to bring out evidence that supports their side and contradicts the other.

Let's see now. An amicus whore is butthurt because he can't inject extraneous material into the record developed by the actual litigants. That does for advocacy what Christian Szell (Sir Laurence Olivier's character in Marathon Man) did for dentistry.

Cry me a river!!

I thought your hatred of black conservatives was extreme.

It's not even close to your hatred of victims' rights lawyers.

Professor Cassell pontificates:

From reading the good professor's biography, I don't see that any indication that he has ever cross-examined a snitch. If after remand the Oklahoma prosecutors have enough chutzpah to put the lying, murdering, bipolar Justin Sneed before a third jury, the jurors will likely check the soles of their shoes to see whether they had stepped in something foul.

The problem is that Glossip's conduct is a lot more consistent with guilt than with being framed by a 'snitch.'

Do you think that the record establishes that it is more likely than not that 1. Sneed was in fact prescribed lithium by Dr. Trompka and 2. He told the prosecutor about it?

What I think doesn't matter at all. When a prosecution witness lies under oath, due process requires that the prosecutor correct the falsehood. That obligation applies with special force when that witness's credibility is the central issue of the trial.

It matters as much as what anyone else thinks, which is all we’re talking about.

Not according to the Supreme Court!

The last I knew, Napue v. Illinois, 360 U.S. 264 (1959), and Giglio v. United States, 405 U.S. 150 (1972), are still good law.

Precisely—and as noted by the majority in this very case, this kind of violation requires showing that the prosecutor knew the statement was false. Which is why I asked whether you think the record establishes that.

"One final note: The Court has sent the case back for a retrial. The evidence in this case is overwhelming. The family remains confident that when that new trial is held, the jury will return the same verdict as in the first two trials: guilty of first degree murder."

If the AG wanted to have him free for political reasons, why would he bother to retry him?

The argument seems to be that in effect he can have his cake and eat it too. Also, he is not seeking "freedom" as such.

https://reason.com/volokh/2024/10/03/glossip-v-oklahoma-how-death-penalty-opponents-concocted-a-brady-violation-and-got-supreme-court-review/

Gotchya. Thank you Joe. 🙂

Third time ain't always a charm. If i am understanding, this dude has served 20+yrs of death row, has had two full trials, countless post conviction appeals, etc...his own lawyer was incompetent in the first trial, the State in the second, the person who actually killed the victim is serving life w/out parole for snitching on this dude to avoid the death penalty and now defendant goes back for his 3rd murder trial [witnesses missing? Any cops die of old age by now?] still facing the death penalty??

The mind boggles.

Sorry your lost this case, Paul. Don't worry...lots of people in prison will be murdered by the State each year. Almost all of the them guilty. You may have lost the battle, but you're winning the war.

Did the only person who connected Glossip to the murders, the murderer himself, lie on the stand?

Yes

If that is OK with you then I hope you are sitting in the dock someday with your life on the line.

THe standard in this country is not put everyone we think is a murderer in jail, it is beyond a reasonable doubt.

The sole witness lying on the stand is reasonable doubt

They did not just declare the man innocent, they called for a new trial

Among the revelations: A box of financial records, potentially key to determining if any money was missing from the motel, was destroyed while Glossip’s first conviction was on appeal. By the time he was retried, the evidence was gone. In marking the evidence for destruction, the DA’s office falsely claimed that Glossip’s appeals had been exhausted; oddly, the box was also assigned a new case number, a move that would effectively hide it from anyone searching for the evidence.

Since then, the firm has released additional startling information, including that Sneed considered taking back his story about Glossip. In 2003, a year before Glossip was retried, Sneed wrote to his public defender, Gina Walker, asking, “Do I have the choice of re-canting my testimony at any time during my life, or anything like that.” In 2007, he

I find it fun that the the supposed motive was that Glossip was stealing from the motel.

What records disappear?

The motel financials?

Now one would think that the prosecutors would have wanted those records front and center at the trial, to prove motive

Nope apparently not in the trial record, so no they didn't

better make them disappear

And the pieces of human garbage alito and thomas clutch their collective pearls about how the majority disrespects the prosecutors

Indeed

Appellate courts decide cases based on the record they have. The defendant could not have introduced favorable evidence on appeal. A third-party amicus certainly cannot. This is a basic aspect of appellate law and I'm shocked anyone with legal training would be ignorant of this.