The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

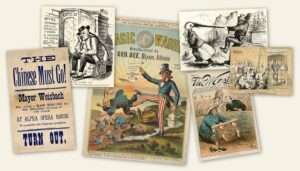

The Economic Impact of the Chinese Exclusion Act

New National Bureau of Economic Research study shows this notorious law not only harmed would-be immigrants, but also damaged the US economy and reduced employment opportunities for native-born whites.

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which barred most Chinese immigration, was one of the most important immigration restrictions in American history. It barred large numbers of Chinese immigrants, condemning them to a life of poverty and oppression. It also set the stage for later immigration restrictions. Perhaps even more significantly, it led to the Supreme Court's awful ruling in the 1889 Chinese Exclusion Case, which ruled that the federal government had a general power to restrict migration, despite the absence of any textual or originalist basis for it. That, of course helped make future immigration restrictions possible. Elsewhere, I have argued the Chinese Exclusion Case should be added to the "anti-canon" of constitutional law.

A new study for the National Bureau of Economic Research, authored by economists

This paper investigates the economic consequences of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, which banned immigration from China to the United States. The Act reduced the number of Chinese workers of all skill levels residing in the U.S. It also reduced the labor supply and the quality of jobs held by white and U.S.-born workers, the intended beneficiaries of the Act, and reduced manufacturing output. The results suggest that the Chinese Exclusion Act slowed economic growth in western states until at least 1940.

This should not be a surprising result. Immigrants contribute disproportionately to economic growth and innovation, and nineteenth century Chinese immigration did so, as well. The result is also consistent with modern data indicating that mass deportations of immigrants destroy more jobs for native-born citizens than they create.

The study does not prove that no white workers were ever displaced by Chinese immigrants. Some almost certainly were. The authors of the NBER study point this out, and note that the Exclusion Act benefited "local" white miners competing with Chinese miners. But such effects were outweighed by the much larger number of white workers who benefited from Chinese migration, including the associated job opportunities it created. The economy is not a zero-sum game, and the interests of workers from different ethnic and racial groups are more mutually reinforcing than conflicting. I explained this dynamic in a bit more detail here.

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Don’t let the carefully cultivated facade deceive you: Ilya Somin is an Open Borders extremist who opposes any and all limits on immigration. The only question is why he has decided to try and destroy the country that took him and his family in.

Yes, it is disgusting. Somin also posts pro-Ukraine and pro-Israel. What if someone replied to each of these, saying that Ukraine and Israel would be better off if all the Jews were exterminated? That would be similar to what he posts here.

And yet, you’re an advocate of school choice, which will lead to more publicly funded madrasas here in the US. Not a lot of intellectual honesty from you. Just blind hate.

You make a good argument against school choice.

It was all good until the brown people started to wield it

Started?

Islam is a religion and political philosophy, not a skin color.

Immigration does not "destroy" the U.S. It's how we Make America Great.

Immigration, voluntary and involuntary, is what makes American food different from English food.

The "Muslim Exclusion Act" was proposed by the person who won the Presidency in 2016, to cheering crowds, and almost became law.

too bad it didn't, if Moe-hammed Atta et al had been "Excluded" from the US in 2000 a million or so people in the US, Iraq, and Afghanistan would still be alive.

This paper is pretty bogus. It says that some Chinese workers were employed in 1880, so presumably they had some economic benefit. So excluding them would be an economic loss. That's all. The same reasoning would say that abolishing slavery was a mistake.

The development of the American West is a great story. Somin wants to argue that it would have been somehow better with a large population of Chinese workers. Seems very doubtful to me.

In the 1860's and 1870's, before the Exclusion Act, there were 15,000 - 20,000 Chinese working on the western half of the transcontinental railroad. They played an important role in the early part of that "great story" you mention -- the development of the American West. https://news.stanford.edu/stories/2019/04/giving-voice-to-chinese-railroad-workers#:~:text=Reducing%20the%20time%20it%20took,western%20half%20of%20the%20railroad. It is not unreasonable to think that, if not excluded, they would have continued to do so.

Don't forget Hop Sing

...and Hey Boy.

..and of course Hey Girl played by Lisa Lu who is still with us at age 97.

The Chinese worked on the railroad because they undercut White labor's wages. They were exploited with the robber barons getting rich as a result. Maybe that's what Ilya wants -- folks like him getting richer and the rest of us in poverty.

Somin could justify the African slave trade the same way.

People did.

I believe Professor Somin owns multiple railroads.

I hear they'd frequently nap on the job, despite the sanction of being docked a day's pay.

Dunno, from watching Kung Fu back in the 70’s I also assumed they’d be unemployable other than for the railroad due to discrimination.

I think constitutionally Congress clearly has the right to regulate immigration under the commerce clause, naturalization clause, migration clause and necessary and proper clauses.

A simple thought experiment should make that plain: lets pretend Congress does not have the right to regulate immigration, but it does have an absolute right to regulate naturalization.

So does that mean as many people who like can come here, with no right to work permits and a path to citizenship?

That evidently is what Somin is advocating, because the commerce and Naturalization clauses are clear about Congress other powers.

You are correct Sir! (HT E. McMahon)

and if Vlad Putin impregnates a young woman, and she gives birth the instant she gets off the jet at Dulles, Putin Jr. is an Amurican Citizen and can run for Congress in 2050, the Senate in 2054 and POTUS in 2060 (and a 98 yr old Frankie might vote for him)

Frank

I'm pretty sure he'd say the requirement for work permits is unconstitutional. And he'd have a better case for that than his case for immigration laws being unconstitutional, since most work is intrastate, and thus doesn't honestly fall under the reach of the interstate commerce clause.

His problem is that, if controlling immigration isn't a federal power, then, since by that argument it's not mentioned in the Constitution at all, it becomes a reserved power of states. And I don't think he wants to admit that states can restrict immigration, either.

So, he kind of tries to have it both ways: The federal government simultaneously lacks the immigration power, AND occupies the field to the exclusion of the states. Somehow.

The problem is that the Constitution was written in the18th Century and addressed 18th Century concerns. Consequently no conservative reading of the Constitution can address a situation – mass immigration of “undesirables” – that arose 100 years later.

I wouldn't quite phrase it that way, but I occasionally make a similar point: The Constitution was written for a small agrarian federation, by people who did NOT have modern attitudes or political views.

If you find yourself liking all of it, it can only be because you're misinterpreting part of it.

But not liking what it means doesn't CHANGE what it means!

The problem as I see it is that, in the early to mid 20th century the federal government started wanting to do things that the Constitution pretty clearly did not authorize. And there wasn't actually a public consensus that it SHOULD be doing them, so amending the Constitution to authorize doing them wasn't feasible.

At that point the legal thing to do was to either achieve that consensus, or just give up on doing those things. But FDR wasn't big on letting the Constitution stand in the way of what he wanted to do.

So instead he suborned the judiciary into pretending they were authorized. First by intimidation, and then staffing it with people who'd agree to the pretense voluntarily.

And the gulf between what the plain text of the Constitution authorizes the federal government to do, and what the courts interpret as permitting the federal government to do, has just kept growing.

And there's still no public consensus that the federal government should have all these powers, so amending it to actually grant them is still off the table. But it giving them up is also off the table politically.

So originalists have been giving up and embracing a sort of constitutional adverse possession doctrine to try to legitimize the fact that our government just routinely violates the Constitution, and is never going to stop doing so.

I agree with the first sentence.

(The migration clause might do implicitly, but the general idea takes you to the same place -- the Constitution in multiple places provides grounds to regulate immigration.)

" . . . condemning them to a life of poverty and oppression."

Prof. Somin, while I generally agree with you on immigration issues, the 1882 Exclusion Act did not 'condemn' anyone.

It obviously reduced opportunities here in the US, but it was the contemporary, imperial Chinese govt that condemned them to poverty and oppression.

If outlets were closed off, the law could have helped to condemn.

There's a fundamental, categorical difference between harming somebody, and failing to rescue them from harm.

But Somin rejects that notion, apparently. Which is why I say he's not so much a libertarian, as he is a universal utilitarian with some libertarian constraints. He seems to think a country's government has actual obligations to non-citizens, rather than the rights of non-citizens merely being side constraints.

If the Constitution didn't enact Spencer's Social Statistics, neither did it enact Rawls' A Theory of Justice. He needs to recognize that.

Nothing in the constitution? Nonsense. The constitution contains an Importation and Migration clause, which explicitly gives Congress power to restrict migration, any way it wants, after 1808. Absent that clause, states would retain complete plenary power over the subject as sovereigns, and indeed did so fully until 1808.

Professor Somin has also had to block himself from the obvious fact that all independent countries regulated immigration to some extent. It’s a fundamental power of independent sovereign states that the States acquired with the Declaration of Independence. Any aspect of that power that the states didnmt cede to the federal government, they kept for themselves.

This is really a Professor Somin special. He had to roll up the constitution really tight and smoke it so hard he completely fogged out the plain-as-day text, to get himself to believe that nothing in the constitution permits any branch of government to restrict immigration.

It's aspirational constitutional interpretation: Not interpreting it as an impartial reader would, or as it actually is by the courts, but instead as he'd like it to be interpreted.

Since his views on open borders are far enough from public opinion that they stand no chance of being democratically implemented, his only hope is that the courts will impose them.

Love how even in the 18th Century people would put stuff off for a later date, I'm sure 1808 seemed far into the future, people would probably have Books that turned their own pages and carriage wheels that didn't get out of round.

It wasn't that far off in the future, it was only 20 years after the Constitution was ratified. Most of the Founders would have expected to still be around by then.

In 1980, 2000 wasn’t that far in the future but it sure seemed like it was

The word "explicitly" means the opposite of what you think it does. (Or the Constitution says the opposite of what you think it does.)

The constitution explicitly forbids Congress from restricting migration prior to 1808. It does not explicitly say that Congress can do so after 1808. That is implied, which is the opposite of explicit.

Absolutely right, implied rather than explicit. Mind you, pretty strongly implied, since there was absolutely no point in prohibiting until 1808 exercise of a power Congress didn't have in the first place.

You might prohibit it's exercise entirely, just as an exercise in redundancy, as the Federalists characterized the Bill of Rights prohibiting what Congress didn't have the power to do anyway. But prohibit it until a certain date?

Makes no sense at all unless it's assumed Congress actually did otherwise have that power.

Almost never do prospective economic impacts of particular policies inform the constitutionality of any law. (A major caveat being attempts at regulating interstate commerce, having nothing to do with “immigration”.)

There is no history or tradition of selective immigration restrictions economic impact being relevant to their constitutionality. Just like with tariffs, Congress is free to enact a policy which has a negative economic impact, if it chooses to do so in its infinite wisdom.

This is once again Somin trying to pretend there is a constitutional mandate for his policy preferences.

It's not like his policy preferences are ever going to have a popular democratic mandate. So it's constitutional or nothing. And he really does not want to admit that it's nothing.

If you believe in something really, really, really strongly, then surely it must be in the constitution somewhere, mustn’t it? Just roll up the Constitution and smoke it, and if you close your eyes and click your heels three times, you will find it in the penumbras and emanations of the resulting constitutional vapors.

Thinking about Somin's take on open borders, and that book I recommended in the other thread, I wonder how his demand for freedom of entry interacts with space colonization?

We're, ideally anyway, about to embark on a new age of colonization, only this time the colonies won't be displacing any natives, they'll be in presently unoccupied space. Planetary surfaces, orbits, moons and asteroids.

A major driver for early colonization efforts were groups that felt oppressed, and wanted a chance to do their own thing someplace else, where nobody would be able to stop them. I expect this will be the case for space colonization, too.

So, Somin: Supposing people found a space colony, explicitly as a social and/or economic experiment. Does you open borders ideology demand that voluntary communities created from scratch may not control entry? Thus de facto prohibiting social experimentation by creation of voluntary communities?

I'm genuinely curious about whether you've considered this issue.

What if there isn’t enough oxygen for everybody who wants in?

I suspect he'd hypothesize that the newcomers would primarily work at Oxygen production, so it wouldn't be an issue. But I don't know that.

But I'm genuinely curious what he thinks about this issue. Maybe he'd make an exception to his freedom of entry principle, for intentional communities?

Economic efficiency is not the only purpose of a society. The question of whether a large society needs a certain amount of common cultural currency to remain stable strikes me as an open one. Wishing it was so, believing it would be evil if it weren’t so, does not make it so. It may be utterly irrational, completely offensive to reason, for the earth to revolve around the sun rather than the other way around. And yet this offense to reason seems to be something we have to live with.

Just as 15th century reason told us the sun revolved around the earth, 18th century reason told us man was a tabula rasa, a completely rational animal, who could do anything rational moralists asked of him. Just as it turned out to be the case that the earth doesn’t always behave rationally but instead revolves around the sun rather than behaving as reason dictates it should, it may turn out to be the case, indeed there is already significant evidence that it is the case, that human beings are not always capable of behaving completely consistently with what rationalists consider rational behavior.

Today’s universities are controlled by rationalists not unlike those who thought Gallileo’s thesis offensive to reason. Professor Somin, despite his differences from most professors, is in essence part of this group.

It may be that people who are members of a large society have to have at least something in common with each other, have to have some not entirely rational basis for feeling they can trust each other, to avoid having that society split into warring tribes. In addition, a society that manages to avoid devolving into civil strife may have to do so at the expense of economic efficiency.

We may not like it. It’s utterly offensive to our sense of reason. But it may be so.

I am not defending the Chinese Exclusion Act. I am simply pointing out that in general, cultural conservatives may have a point. A society that optimizes individual liberty and economic efficiency, Professor Somin’s rationalist lodestars, may for reasons we may not like turn out not to have a very long life, indeed to end up nasty, brutish, and short.

This idea is no doubt as outrageous, as offensive to reason, as the idea of the earth revolving around the sun in Galileo’s time. And as was the case then, there are excellent rational arguments against it.

But it may nonetheless be so.

I recall suggesting some years ago that Professor Somin use a more pragmatic approach to argue for broad immigration by emphasizing the historical benefits of immigration to host countries (e.g. immigrants helped Prussia move from being a backwards country to a major power jn the 17th and 18th centuries), and also problems that countries with very restrictive immigration have experienced (e.g. Japan’s aging population and difficulty supporting ever-more retirees with ever-fewer workers.)

Nonetheless, it might be better to focus on more clearly empirically verifiable outcomes than posited outcomes derived logically from theory.

From this point of view, the Chinese Exclusion Act is a poor example. The United States in fact grew enormously despite the Chinese Exclusion Act. It might perhaps have grown faster still without it, but there isn’t any ready way to actually verify this. It’s just a derivation from theoretical assumptions. You don’t actually SEE any harm. There’s no observable decline. There was so much immigration and so much visible growth in this period as to make the possibility there might have been somewhat more growth with somewhat more immigration unobservable, unverifiable.

Japan is different. You actually see problems with your eyes, problems whose existence you can verify empirically. That’s what makes it a much more credible example. Similarly, with both Prussia and the United States earlier in its history, you can observe, you can empirically verify, the growth with the immigration that was allowed.

I’m going to suggest not only making more pragmatic arguments, but also making more empirically verifiable ones, relying less on effects whose existence you can only get to by first believing a bunch of theoretical assumptions, and that you can’t actually empirically observe.