The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

On Copyright, Creativity, and Compensation

Copyright infringement hits home - a cautionary tale.

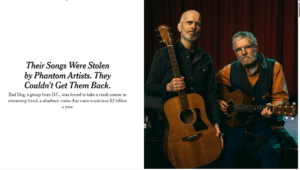

Some of you may have seen the article by David Segal in the Sunday NY Times several weeks ago [available here] about a rather sordid copyright fracas in which I have been embroiled over the past few months. [That's me, seated on the right in the photo].

It's a pretty wild story. If you don't feel like reading the whole NYT article, here's a brief summary of how it unfolded:

Off and on, for 30 years or so, I've been in a duo ("Bad Dog") with a friend, Craig Blackwell, here in Washington DC: Two acoustic guitars, two vocals, original songs. We take the music we make very seriously, but we are not professional musicians; we both had and have careers outside of music. We weren't and aren't in it for the money, but just for the pleasure of making music and the satisfaction one gets from creating something worthwhile and interesting and, perhaps, even beautiful.

In early 2023, we recorded an album containing nine new songs ("The Jukebox of Regret" - you can listen to it here) at a local recording studio (Mixcave Studios). After the recordings were mixed and mastered, we posted them (as we had posted other recordings that we had made over the years) on the "Bad Dog" page at Soundcloud.com, a music-sharing website.

Several weeks later, a friend told us that she had input a recording of one of our songs (entitled "Preston") into the Shazam app, and that Shazam identified the song right away -- as something called "Drunk the Wine" by someone called Vinay Jonge. It pointed her to the YouTube page where the recording was available to be streamed.

Well! The YouTube recording was, it was clear upon listening to it, an exact duplicate of the recording we had posted on SoundCloud. A quick Google search on "Vinay Jonge - Drunk the Wine" turned up his recording - i.e., our recording of "Preston" - at all the other major music streaming services (Spotify, Amazon Music, Apple Music, allmusic.com, etc.). [Curiously, Mr. Jonge didn't seem to have any other songs posted anywhere on the Internet. A one-hit wonder!].

We began the process of sending "takedown notices" to each of the streaming platforms, informing them that they, and Mr. Jonge, were infringing our copyright.

And then we learned that it wasn't only "Vinay Jonge," and it wasn't only one song; all of the songs on the album had been pirated and were posted on all of the big streaming platforms. Each one had a new song title and a new artist name:

- our "The Misfit" had become "Outlier" by Arend Grootveld;

- our "Verona" had become "I Told You" by Ferdinand Eising;

- our "A Drink Before I Go" had become "Drink When I'm Gone" by Amier Erkens;

- our "Pop Song" had become "With Me Tonight" by Kyro Schellen;

- etc.

You might ask: How did we figure this out? Good question! Searching for "Bad Dog - Preston" or "Verona" or "The Misfit" at Google or YouTube or Spotify or Apple Music etc. wouldn't have turned anything up, because the song names had all been changed, and each song was associated with a different "artist." Without knowing how our songs had been re-titled, or the names of those who were taking credit for our work, the infringements were completely invisible to us, out there in the great Internet ocean.

So how did we track them down? The answer is: We found these other infringing files after we sent the nine song files to Disc Makers, a commercial CD printing operation, to have them print up some CDs for us to hand out at our upcoming album release show. Disc Makers apparently uses some sort of file-matching software/system to check at least some of the streaming platforms for duplicate files; they found the infringing files, and they sent us a polite note with a list of everything they had found, and informing us that they had put our CD project on "Hold," because the files we sent them "contain previously copyrighted material."

Disc Makers, in other words, thought - not unreasonably, I suppose, given the evidence it had - that we were the infringers! Until we were able to persuade them that it was the other way around (which we were able to do by demonstrating that the upload date of the files we sent to SoundCloud pre-dated the upload dates for the infringing files) they wouldn't make the CDs for us.

One final plot twist. Now that we had the "artist" names and the new song titles, we could locate infringing files at the streaming platforms, and we started sending out more takedown notices. In response to one that we sent to Apple Music, we got a note back saying, in effect: "The songs you have identified were provided to us by a music distributor. If you have a copyright claim, please direct it to the distributor." And they identified the distributor: Warner Music Group.

Well! That was a surprise! Warner, of course, is one of the world's largest distributor of digital music, with thousands of musicians under contract, and a pipeline that extends to all of the big streaming platforms. Apparently, Warner had some sort of relationship with Vinay Jonge, Amier Erkens, Arend Grootveld, and the rest of them under which Warner distributed "their" music to the streaming platforms (and, I assume, took a small percentage of whatever streaming income those tracks generated). Also apparent: whatever system Warner uses to insure that the artists they represent own the copyrights in the material that they deliver to Warner did not function adequately in this case. [The folks at Warner declined my request to comment on this article]

What to make of all this? I am not oblivious to the irony of being confronted with this problem after having spent 30 years or so, as a lawyer and law professor, reflecting on and writing about the many mysteries of copyright policy and copyright law in the Internet Age.

Here are a few things that strike me as interesting (and possibly important) in this episode.

1. What's the big deal?

The nature of the legally-cognizable injury that we suffered as a result of all this is worth a more detailed look.

The unauthorized reproduction and distribution of our songs is, without question, actionable copyright infringement. Blackwell and I, as copyright owners*, have the exclusive right to reproduce, and to publicly distribute, the songs to which our copyright attaches, and to authorize others to do so. We did not authorize Jonge (or his colleagues) to do that. Copyright infringement is a strict liability offense; whether or not Messers. Jonge et al. knew that the files we posted on SoundCloud contained copyright-protected works is entirely irrelevant. It's a slam dunk case.

*There are, as the copyright nerds among you well know, two separate copyrights attached to each song, both of which were infringed here: A "musical works" copyright, which protects against unauthorized reproduction and distribution of the song itself (words and music), and a "sound recording" copyright, which protects against unauthorized reproduction and distribution of our particular recorded performance of each song.

But the harm that we suffered as a consequence of those actions is relatively - perhaps vanishingly - small. Remember, we had placed the recordings on SoundCloud for the sole purpose of getting people to listen to them. Thanks to the efforts of Vinay Jonge and his pals, many of our songs have now been streamed tens of thousands of times on Spotify and YouTube. Hooray!

There is another injury, of course, and it is the one that really matters, for the two of us, given our particular circumstances. It's not the one arising from the unauthorized reproduction and distribution per se, but the injury arising from the false attribution accompanying those unauthorized reproductions and distributions. That's what really (to use the technical legal term) "pisses us off." That those tens of thousands of listeners now associate "Preston" - a song that Blackwell wrote, and that we have been playing and working on for 30 years - not with Bad Dog, but instead with that elusive genius, "Vinay Jonge."

For us, that is largely a "dignitary" harm, an injury to our "person-hood," akin to the harms underlying the torts of libel, or invasion of privacy, or intentional infliction of emotional distress, entirely independent of whether or not we have suffered any economic loss. It's not, in other words, about the money - but no less real for all that.

I realize, of course, that for many musicians whose music has been similarly ripped off (see [2] below), this kind of false attribution does impose substantial economic harm. Free distribution of one's work over the Internet has become, for anyone trying to earn a living as a performing musician, or as a composer/songwriter, an indispensable part of getting people to pay you to stream your music, to come to see your live shows, to record the songs you have written, to hire you to teach them how to play the piano or violin or guitar, etc. For these folks, substantial economic harm, in addition to the dignitary harm, can arise from the false attribution.

Interestingly (at least to this ex-copyright lawyer) that injury - the one arising from the false attribution - is not one that U.S. copyright law protects against. Copyright law gives creators a set of exclusive rights which does not include the right to have their works correctly attributed to them. Vinay Jonge's act of putting his name to our song, standing alone, doesn't infringe our copyright.

I think this comes as a surprise to most people. It means that if we had authorized Mr. Jonge to distribute our songs to the streaming platforms, and he did so under his own name, while we might well have a claim against him for breach of contract, or for unfair competition, or for "passing off," we wouldn't have a copyright claim against him, because the Copyright Act does not include the right of attribution in the bundle of rights granted to the copyright owner.

The copyright laws of many countries - most notably, throughout the EU - do protect the attribution right, and there has been a long-standing debate as to whether, and to what extent, the U.S. should follow suit. I've never been a big fan of efforts to do so, and I don't think I've become one now; the last thing the Copyright Act needs is an additional set of rights to over-complicate an already over-complicated statute. But the whole episode has certainly given me more of an appreciation for the significance of the attribution principle.

2. Scale and automation

Though I might like to flatter myself with the notion that Messrs. Jonge, Grootveld, Schellen, and the others chose our music to steal because they loved the interplay between our guitars, or because they were moved by the lyrics to our songs, I'm pretty sure that's not how this went down.

While I don't know exactly how our songs ended up on Apple Music and the other streaming sites, here's what I think happened. First off, the names of the infringers - "Vinay Jonge,""Arend Grootveld," and the rest of them** - do not identify real people. The names are all made up; I wouldn't be at all surprised if there were a single person or entity behind all of them.

**Here's the entire list of "artists" whose names appeared with our recordings on one or another of the streaming platforms: Vinay Jonge, Arend Grootveld, Gaston Mailly, Ferdinand Eising, Seth Klompmaker, Kyro Schellen, Amier Erkens, Janco Rossem, Enzo Pruijmboom, Rivaldo Laak, Tuur Jonk, Rashied Amelsvoort, Lennert Olivier, Tjark Warnaar.

Fabulous, don't you think? Tjark Warnaar?! The list reads like the roster of the Olympic hockey team from some unrecognizable but vaguely Scandinavian land. And by strange coincidence, each one stole one, but only one, of our songs

And I doubt that anything as inefficient and time-consuming as actually listening to our music took place before the recordings made their way to the streaming platforms. This is a money-making scheme that can yield some serious money, but only if it can be automated to operate at scale. There's a vast ocean of music - tens of thousands of hours of music uploaded every day - that is freely distributed on Instagram, SoundCloud, YouTube, Bandcamp, Facebook, etc. I strongly suspect that "Mr. Jonge" - or whoever stands behind that pseudonym - chooses his targets based not upon musical quality but upon simple availability; he sends out his automated crawlers to prowl the ocean and bring back whatever it finds. An automated name-generator creates a fake artist name, an automated lyrics-analyzer finds a new song name,** and off he goes.

**Another of the amusing features of this adventure is that the new names given to the songs were clearly not chosen at random, but always had some semantic relationship to either the original title or to the song lyrics themselves. "The Misfit" became "Outlier"; "Preston" (with the lyric "Preston stuttered and he drank the wine") became "Drunk the Wine," etc.

If he can get a distributor to post your recordings to Spotify and the other big for-pay platforms, you might earn around $0.002 per stream; 10,000 streams will get you about 20 bucks. Not too exciting - unless he can do this for 1,000, or for 10,000 songs, at which point we're talking about real money.

Whoever found a way to take our recordings and to re-package and monetize them would be capable, I would think, of replicating that for thousands or hundreds or thousands of songs which are made freely available out there on the Internet. Given the substantial amounts of money you could make that way, I wouldn't be at all surprised if enterprising entrepreneurs, with rather dubious moral codes, are hard at work on the problem.

If I'm right about that, then there are thousands and thousands of musicians out there whose music is being monetized by others in precisely this fashion, and who have absolutely no idea this is happening. If you posted recordings on Bandcamp or SoundCloud that were subsequently "Vinay-Jonged," and made available under some fake name at Spotify or Apple Music, you can't find them using the search tools Spotify and Apple make available to you. The only way to find them is for Spotify and Apple to run some file-matching algorithm that compares, bit for bit, the file you uploaded against the files in the Spotify or Apple databases, and that's not something Spotify or Apple will do for ordinary users.

I'm no class-action lawyer, and have no intention of becoming one, but if I were I might take some time to investigate this a little further, no?

Notice and takedown

As described above, we spent a considerable amount of time searching for infringements on the major streaming platforms (once we knew what we were searching for), and then, once we found them, sending in "takedown notices" to the platforms.

The Copyright Act's "notice-and-takedown" provision (codified in Section 512(c) and 512(g)) was one of the centerpieces of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, enacted in 1998. It is one of the least artfully drafted statutory provisions in the entire US Code, but basically it works as follows:

The N-and-T scheme gives "service providers"** an immunity from copyright infringement liability, provided certain conditions are met. Such an immunity is immensely valuable, even for relatively small Internet operations, let alone for the Internet giants (YouTube, Spotify, Instagram, et al.) that post tens of millions of user-uploaded files every day, both because (as noted above) copyright infringement is a strict liability offense, and because copyright owners can obtain fixed statutory damages*** of at least $750 for each infringement regardless of whatever actual financial damage they may have suffered.

**"Service provider" is broadly defined to include Internet intermediaries of all kinds: all entities "transmitting digital online communications … between or among points specified by a user, of material of the user's choosing, without modification to the content of the material as sent or received." Facebook, YouTube, Spotify, Instagram, X, TikTok, Reddit … virtually the entire universe of social media platforms, and much besides, are within the definition.

***Section 504(c) provides that "the copyright owner may elect, at any time before final judgment is rendered, to recover, instead of actual damages and profits, an award of statutory damages for all infringements involved in the action, with respect to any one work … in a sum of not less than $750 or more than $30,000 as the court considers just."

The immunity, however, is only available to service providers who, upon receiving a notice from a copyright owner asserting that material residing on the provider's system is infringing, "respond expeditiously to remove or disable access to the material that is claimed to be infringing."**

**The provider must also simultaneously notify the user who uploaded the material in question that an infringement claim has been filed, and must allow the user an opportunity to file a counter-notification disputing the infringement; upon receipt of such a counter-notification, the provider must "replace the removed material and cease disabling access to it" within 14 days in order to remain eligible for the immunity.

The N-and-T scheme was quite innovative at the time it was enacted, and extremely controversial as well. Many copyright owners objected to the fact that it placed the burden on them to find infringing material, and that it imposed no duty on the service providers to search for or locate such material. I thought at the time, as a participant in many of the discussions and debates that led up to enactment of the N-and-T provisions, that that was the right call, and I still do.

But notice-and-takedown can only perform its task of deterring infringement if copyright holders can reasonably be expected to locate infringing material. That doesn't appear to be the case here. The platforms have the technology available to check their databases for identical copies of copyrighted material, and they use that technology at the behest of some copyright owners whose material is distributed to the platforms by their "trusted partners." Warner Music, that is, can and does get YouTube and Spotify and Apple Music to check for uploads on their streaming systems that infringe the copyright of Warner-represented artists whose music Warner has distributed to the platforms. But those tools are not made available to ordinary users who do not have a contractual relationship with YouTube and Spotify and Apple Music.

If I am correct in my speculations about the size and scale of these scam operations, that would appear to be a rather significant lacuna in the statutory coverage.

The DMCA itself may point to a way out of this dilemma. Section 512(j) already provides for an additional condition of eligibility for the immunity: A service provider cannot assert the immunity unless it "accommodates and does not interfere with standard technical measures," which are defined as

"technical measures that are used by copyright owners to identify or protect copyrighted works that

(A) have been developed pursuant to a broad consensus of copyright owners and service providers in an open, fair, voluntary, multi‑industry standards process;

(B) are available to any person on reasonable and nondiscriminatory terms; and

(C) do not impose substantial costs on service providers or substantial burdens on their systems or networks."

I don't, to be perfectly candid, know nearly enough about file-matching technologies whether they meet, or could be configured so as to meet, these requirements. But I think that the spirit, if not necessarily the letter, of this provision can serve as the foundation for some kind of an obligation on the platforms' part to facilitate user identification of infringing material.

Show Comments (50)