The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

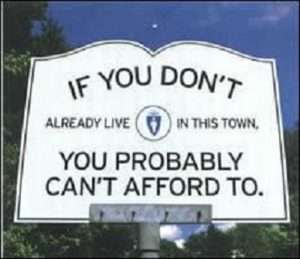

A Flawed Attempt at a Libertarian Defense of Exclusionary Zoning

Robert Poole's effort to defend exclusionary zoning falls prey to a combination of logical fallacies and factual error.

For many years, libertarian economists, housing experts, and legal scholars have been at the forefront of efforts to oppose exclusionary zoning. Regulations restricting the type of housing property owners can build on their land severely constrain property rights and also cause immense economic and social harm by excluding millions of people from areas where they could otherwise find better job and educational opportunities. Libertarian legal scholar Bernard Siegan was a pioneer critic of zoning as far back as the 1970s, and other libertarian-leaning experts have made more recent major contributions to this literature, most notably those of Harvard economist Edward Glaeser. Few ideas are as central to libertarianism as the notion that private property owners have a strong presumptive right to use their land as they see fit, subject only to those restrictions they voluntarily accept.

In a recent Reason article, Robert Poole challenges the standard libertarian view on these issues by offering a defense of single-family zoning. The latter is one of the most severely restrictive types of government-imposed land-use constraints. It bars a vast range of housing options, including duplexes, quads, apartment buildings, and much else. Poole's defense of single-family zoning founders in a morass of logical and factual errors. Here is an excerpt from it:

When zoning laws began to proliferate in the 1920s, they were a newly imposed restriction on what homeowners could do with their properties. In those days, most people lived in long-established communities in cities. Today, after 70 years of suburbanization following World War II, the large majority of homeowners bought their homes in suburbs built in response to market demand for single-family living. Local governments (typically county governments outside the main city) responded to the kind of housing the developers wanted to create to meet the growing single-family market demand.

In effect, postwar single-family zoning represented an agreement under which homebuyers accepted restrictions on other types of uses in their neighborhood in order to be protected from negative externalities that neighbors might create, without the protection of the covenant provided by single-family zoning.

It is simply not true that single-family zoning restrictions were a response to "market demand" that property owners voluntarily agreed to. In reality, these rules were - and are - imposed by government coercion, including on many property owners who would have preferred to build multi-family housing on their land. At best, one can say that these policies met a "demand" that some property owners had for imposing constraints on others.

By that standard, almost any form of government intervention can be defended as a response to "market demand." Protectionism is a response to "market demand" from producers who seek to be free of foreign competition. Price controls are a response to "market demand" for lower prices. Even socialism can be justified as a response to "market demand" from those who prefer a collectivist society.

In his description of the historical origins of single-family zoning, Poole also omits the large role of racism. In many places, such policies were enacted as a seemingly neutral tool for excluding blacks and other racial minorities, after the Supreme Court invalidated explicit racial discrimination in zoning in 1917.

It is true that single-family zoning can sometimes protect homeowners against externalities. For example, some affluent homeowners dislike the aesthetics of mixed-use housing, and others may prefer to live in an area with few or no working or lower-middle class residents. Others simply want to avoid changes to the "character" of their neighborhood. But exclusionary zoning creates far larger negative externalities than it prevents, most notably by excluding millions of people from housing and job opportunities, thereby also greatly reducing economic growth and innovation. Moreover, even many current homeowners in areas with zoning restrictions stand to benefit from their abolition.

Poole also tries to defend single-family zoning restrictions by claiming that they are a kind of "contract":

To abolish single-family zoning is a violation of the contract between a municipality and its single-family homeowners. They selected the neighborhood and the house based on the protections offered by prevailing zoning.

The simple answer to this argument is that no such "contract" exists. A true contract arises through the voluntary agreement of the parties. By contrast, zoning restrictions are imposed by governments on all property owners in a given area, regardless of whether they agree to it or not.

It is true that, after the initial coercive imposition of zoning, some of those who buy property in the area may do so in part because they like the restrictions. But if that qualifies as a "contract" that future government policy is morally bound to respect, the same goes for virtually any other type of coercive government policy that some people have come to rely on.

We could equally say that protectionism is a "contract" between the government and protected industries. After all, many investors and workers may have "selected" that industry "based on the protections offered by prevailing" trade restrictions. Similarly, abolishing racial segregation violated the "contract" between the government and white racists who "selected" segregated neighborhoods "based on the protections offered by prevailing" segregation laws.

Libertarian economist David Henderson offers a similar critique of Poole's argument here. As he points out, "[w]henever government gets rid of restrictive regulations, people who gained from those regulations will lose. But that doesn't mean that the government violated a contract."

There may be some situations where completely abolishing unjust government policies that violate libertarian principles would be wrong, because of reliance interests. The most compelling examples are cases where people rely on welfare programs, without which they might be reduced to severe poverty. If, someday, libertarians succeed in abolishing Social Security, there will be a strong case for exempting the elderly poor who have come to rely on that program, and have no other way to support themselves. But few if any beneficiaries of single-family zoning restrictions are likely to suffer any comparably terrible privation if those restrictions are abolished.

In another part of his article, Poole analogizes single-family zoning to private land-use restrictions, such as private planned communities. This analogy (more often made by left-wing critics of private communities), is badly flawed for reasons I summarized here. The most important distinction is that, unlike zoning, private land-use rules really are contracts that only bind those landowners who have voluntarily consented to them:

The requirement of unanimous consent ensures that [private] restrictions rarely, if ever, violate owners' property rights. It also makes it unlikely that HOAs and other private communities can significantly restrict mobility in the way zoning restrictions do. It is nearly impossible for an HOA with severe restrictions on building to take over a vast area, such as a major metropolitan area or even a good-size suburb. The city of Houston, which has no zoning, but gives relatively free rein to HOAs, is an excellent case in point. The extensive presence of HOAs hasn't prevented Houston from building large amounts of new housing, and featuring far lower housing costs than cities with zoning restrictions. Indeed, the city's openness to consensual private land-use restrictions may even have facilitated new housing construction by allowing those who really want restrictions to create small enclaves for themselves instead of imposing those rules on everyone else.

In his article, Poole rightly praises Houston's policies. But he fails to recognize the fundamental distinction between them and government-mandated single-family zoning.

Poole claims that single-family zoning restrictions do not significantly constrain new housing construction, and that the best way to address the housing crisis is to focus on lifting restrictions on the development of previously undeveloped land. I agree the latter should be abolished. But exclusionary zoning rules are also a major constraint on housing construction. In suggesting otherwise, Poole ignores a vast amount of research compiled by economists and land-use experts across the political spectrum. Recent evidence suggests that the effects are even larger than previously thought.

Allowing more development in currently undeveloped areas is not an adequate substitute for zoning reform. Much of the benefit of the latter comes from increasing the availability of housing in places where there are important job and educational opportunities. Most undeveloped land is relatively further away from such locations, and building more housing there offers fewer benefits than allowing increased construction close to major centers of commercial and social interaction.

Finally, Poole complains that "preemption of local government policy violates basic principles of limited government: that any government action should be carried out at the lowest possible level of government." I always thought that one of the most basic principles of limited government is that private property owners should be allowed to decide for themselves what they can build on their own land. Allowing them to do that actually promotes greater diversity and decentralization of power than leaving that authority in the hands of local government.

Poole's article also contains a number of other errors. For example, it is not true that California "recently [became] the first state to enact legislation that invalidates single-family zoning, as an effort to increase housing supply." Oregon enacted a state-wide ban on single-family zoning in 2019 (exempting only communities with fewer than 10,000 residents). SB 9, the California law Poole refers to, is less far-reaching. It allows owners of property in areas with single-family zoning to build additional housing units, but only if they meet a variety of restrictive criteria. SB 9 is an important step in the right direction, but does not completely abolish single-family zoning.

In sum, Poole's defense of single-family zoning restrictions is at odds with libertarian principles. More importantly, it's based on weak arguments that should be rejected regardless of their ideological valence.

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

"It is simply not true that single-family zoning restrictions were a response to "market demand" that property owners voluntarily agreed to. In reality, these rules were—and are—imposed by government coercion..."

Perhaps "market demand" wasn't a great choice of words. Poole should have said "representative government." If a large number of property owners are in favor of single family zoning, and they lobby their representatives in local government to pass such zoning, isn't that just the way our system is supposed to work? People who are against such zoning will call it government coercion, but it's just government responding to the will of the people it represents.

Obviously there are limits to this, when the majority will infringes on the individual rights of the minority. And maybe zoning is such a case, or maybe not. But I don't find the overarching principle being expressed here very convincing.

People who are against such zoning will call it government coercion, but it’s just government responding to the will of the people it represents.

But what if the will of the people, as reflected in municipal government, changes?

Then the zoning would change, I suppose.

re: " isn’t that just the way our system is supposed to work?"

No. Emphatically, no. We do not live in a direct democracy. Direct democracy is parodied as "two wolves and a sheep voting on what's for dinner." There is a significant kernel of truth in that analogy. The Tyranny of the Majority was a serious concern for the Founders and our system has a number of built-in protections against it.

Regardless, Somin is not making a political argument - he is making a moral one. Even if we did live in a direct democracy with the power to pass laws such as you describe, they would be deeply immoral laws because they coopt the property of the minority for the (uncompensated) benefit of the majority. Government "responding to the will of the people" by forcing other people to do what they don't want to is very much "government coercion".

I can't see how you interpreted anything I wrote as support for direct democracy. By "our system," I mean elected representatives being guided by the will of the voters - up to a point, of course. Government is "forcing other people to do what they don't want to do" all the time, it's even occasionally good policy to do so. You can label that as government coercion if it makes you feel better about it.

'some affluent homeowners dislike the aesthetics of mixed-use housing, and others may prefer to live in an area with few or no working or lower-middle class residents"

Its not "affluent homeowners" who are going to suffer if single family zoning is destroyed, its "working or lower-middle class residents". They will get the multi family block busters built that will destroy their peaceful enjoyment of their houses.

Absolutely right. Affluent homeowners will always have the ability to live the way they want to live.

Sure. But what about Hunter and Hillary?

It is coercion and it can be done by incrementally taking small “rights” away under the threat of fines. In our county the zoning code has been changed over the last 2 years taking small steps that are nearly impossible for a homeowner to challenge economically against county government with lawyers on staff to defend their changes. 2 years back we had a B&B category that was for multiple rooms rented in a house and included food being served. They made a change that suddenly a B&B doesn’t require food to be served. A year later the limit is changed from two rooms to one room. Without notice (unless you subscribe to a stupid little local paper) the ability to rent a room in your house on Airbnb (when the owner is there during the stay) suddenly you need to pay thousands of dollars for a permit process that is not guaranteed, have the building inspectors come through your house, get the local National Park Service, the state water department, the county road department and a few other government agencies to say it’s OK to have someone stay in you house for a night even if you’ve been doing it for years. Don’t get the license then you’ll get fined $500 per violation. That’s coercion. It really pisses me off but I don't have thousands of dollars to take them to court to challenge the zoning changes.

Apologies, this is in the wrong place.

The developer who wrote in covenants instead of relying on zoning has created more value for the people who buy into the neighborhood with the intent of living there.

Restrictive covenants are contractual. It is part of the bargain that the homeowner makes when buying into the neighborhood. You agree to maintain your property and to limits on what you can build in exchange for the ability to force your neighbors to do the same. If you don’t like the covenants, then you don’t have to buy in that neighborhood.

If a significantly large number of the owners no longer want the restrictions, they can either change them or simply stop enforcing them, which leads to the restrictions being waived.

Home owners in Houston, which famously lacks zoning of any kind, rely heavily on covenant restrictions to prevent factories and auto shops from opening in their neighborhoods.

This is really a strange and uninformed libertarian fancy, that there is a vast moral difference between a municipality that imposes a single family zoning regime on a tract of vacant land with the consent of the owner as preliminary step in development (the situation Poole is describing) and a developer who records a restrictive covenant regime on the same property prior to development. The main difference is that the zoning alternative allows greater flexibility in response to changing conditions, whereas covenant regimes are typically less flexible.

This is what I was thinking as I read the post.

I mostly agree with a robust property rights argument, but there are some cases where controlling density is important for health and safety.

One example is I used to live at about the 600ft elevation on an 1800' mountain that's base was at 90', there some moderately sloped suburban neighborhoods scattered around it's flanks, but there were only two roads that reached those neighborhoods, and both of them had grades of over 10% on stretches. Allowing multifamily housing when there is no capacity to expand the roads serving the area, and too high of a density might also cause runoff issues on such steep slopes. My own lot required a path with stairs and switch backs to reach the lowest part of my lot from the house.

Other examples would be a valley with a narrow outlet where the roads can't be expanded, or a community with a limited water supply.

It is true that single-family zoning can sometimes protect homeowners against externalities. For example, some affluent homeowners dislike the aesthetics of mixed-use housing, and others may prefer to live in an area with few or no working or lower-middle class residents.

And other affluent homeowners enjoy reassurance that they will not have rendering plants or fireworks factories as neighbors. Sometimes, even less-affluent homeowners are smart enough to see the advantages.

Somin shows lordly disdain for ordinary homeowners who want to protect property rights from free market happenstance—a subject into which Somin's ideological acquaintance seems to have left him strangely short of insight.

Meanwhile, you can't take away a farmer's God-given right to do what he wants with his land. That was what a rural-area county commissioner and planning and zoning board member told me, years ago. That view did not survive a proposal by NL industries—formerly known as the National Lead Company—to set up a smelting operation near his heirloom ranch.

Poole claims that single-family zoning restrictions do not significantly constrain new housing construction, and that the best way to address the housing crisis is to focus on lifting restrictions on the development of previously undeveloped land. I agree the latter should be abolished.

As fate and right wingers would have it, a giant supply of previously undeveloped land has just been reopened in close proximity to many downtown locations. The SCOTUS, with Sackett II, has announced its new political policy to cut the national reserve of protected wetlands approximately in half. Expect a land-rush style competition to fill America's newly exploitable urban-adjacent marshlands, meadows, bayous, and swamps, and install on top of the fill the greatest density development which engineering limitations permit, and they permit a lot.

Houston has taught the nation how to float high-rise buildings on mere muck. That's great news for Somin, and really for any capitalist who understands a maximal-return real estate play when he sees one.

It will be interesting to see which of the various rape, ruin, and run possibilities gets top priority. The soggy parts of northern New Jersey will attract plenty of attention, of course, but wouldn't the highest-prestige trophy go to the developer who engineers the refilling of the Tidal Basin in D.C.? It is an entirely man-made basin, created in the early 19th century, with only man-made connections to other waters. Enlightened design could even leave a few of the famous cherry trees in place, to commemorate the no-longer-needed Cherry Blossom Festival.

And what a location! Practically right on the mall, adjacent to both the Washington Monument grounds and the Jefferson Memorial, and less than mile from the White House. Just wait for a Republican-controlled government, and get going! Is there anything else imaginable which could better demonstrate national commitment to free enterprise than filling the Tidal Basin?