The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

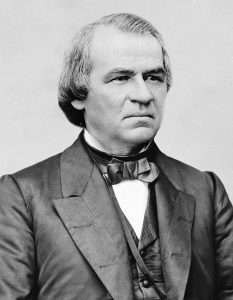

Today in Supreme Court History: February 21, 1868

2/21/1868: President Johnson orders Secretary of War Edwin Stanton removed from office. In Myers v. U.S. (1926), the Supreme Court found that Johnson's actions were lawful.

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Digital Realty Trust, Inc. v. Somers, 583 U.S. --- (decided February 21, 2018): whistleblower statute did not allow damages for retaliatory termination where employee had reported securities laws violations to senior management but not to the SEC

Class v. United States, 583 U.S. --- (decided February 21, 2018): defendant pleading guilty can still appeal on grounds that statute under which he was charged is unconstitutional (carrying a gun on U.S. Capitol grounds, 40 U.S.C. §5104(e)(1), which he argued violated Second Amendment; the D.C. Circuit ended up rejecting this argument, 930 F.3d 460, but that was before Bruen, 2022, where the Court, disagreeing with both parties in front of it, held that cases such as Class applied too lax a standard of scrutiny, see Bruen fn. 4)

Ministry of Defense of Iran v. Elahi, 546 U.S. 450 (decided February 21, 2006): Elahi, an Iranian citizen, sued the Islamic Republic of Iran (he claimed it murdered his brother) in federal court and got a default judgment. Meanwhile Iran's Ministry of Defense won an arbitration award in Switzerland and went to federal court to confirm it, thus locating the award in the U.S. Here Elahi moves to attach it so as to satisfy his judgment. The Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act does not apply to commercial activities of an "agent or instrumentality" of a foreign state but the Court, relying on the opinion of the Solicitor General, holds that the Ministry of Defense is not an "agent or instrumentality" but part of the foreign state itself. Therefore the Ministry of Defense has immunity and the petition for attachment is dismissed.

Gonzalez v. O Centro Espirita Beneficente Uniao do Vegetal, 546 U.S. 418 (decided February 21, 2006): Religious Freedom Restoration Act prevented prosecution of religious sect for using hallucinogenic tea in their services

Blanchard v. Bergeron, 489 U.S. 87 (decided February 21, 1989): 40% (!!) contingency fee arrangement between plaintiff and his lawyer did not place ceiling on amount of fees recovered from losing side in §1983 action (I can personally testify to the ridiculous over-lawyering by plaintiff's counsel in §1983 actions, knowing they can recover for it or at least use it as leverage for settlement)

I think I side with the dissent in Class. A guilty plea waives non-jurisdictional challenges except those explicitly reserved by the defendant. Defendant Class reserved some classes of claims, but not the constitutionality of the statute. Even post-Bruen it is not clear that the statute is unconstitutional in all applications. That leaves an as-applied challenge, which should be first raised in the trial court with supporting evidence. The trial judge, for example, might ask the parties to file briefs discussing 18th century ordinances governing storage of firearms in motor vehicles.

Isn't a guilty plea is the same as a conviction? We often see post-conviction arguments that the statute convicted under is unconstitutional. It has nothing to do with the proof at trial so it's not an argument that would be in the record.

As a matter of policy the courts have to decide what a guilty plea means. It means you admit guilt and all that guilt implies.

There is a rarely used alternative, a bench trial with stipulated evidence. One of the January 6 defendants elected such a trial. He didn't contest what he did. He denied that it constituted obstruction of Congress. The judge said it did. All his appellate rights are preserved.

Thanks.

This is similar to (if not the same as) an "action on stipulated facts". In the New York court system such an action can be brought in the Appellate Division as original jurisdiction, since the general rule is one level of appeal as to facts and two as to law, and you're not appealing any facts. I've recommended it on a few occasions but my adversaries always refused, either because they didn't understand the device or were afraid to try anything new.

Regarding the RFRA case, it is important to note that the drug users harvested the ingredients and made the tea themselves. The Supreme Court did not recognize a right to buy and sell drugs. At least one lower court has explicitly ruled that the RFRA does not grant a right to sell illicit drugs. The distinction is interesting in 2023 because of litigation over whether religious freedom protects abortion. If courts rule consistently with drug cases, they will find a right under the RFRA to abort your own fetus but not to get an abortion from a doctor.

Yuck.

In 1979 Lolly Hirsch and her daughter visited our birth control class to give a talk on “early extraction” self-abortions. The equipment was on the table next to them. They threw me and the other male out of the room so I didn’t get to hear the specifics. I said, “Men need to know about gynecological things outside the context of sexual relations”, or something like that, to no effect. (Our teacher later apologized to me about it.) I’m pretty sure I would have been nauseated, and I wonder if it gave some of my classmates second thoughts about their views on abortion.

A few years later my school biology teacher showed us a video of a woman giving birth. That was as close as we got to sex ed. We didn't have "health" classes. It is possible the girls were rounded up when the boys weren't looking to learn about female parts.

When I was attending middle school and high school (I graduated in 1975), the girls got sex education, the boys did not. It was a conservative town.

I forgot one other bit of sex-related subject matter in biology class. The subject of the hymen came up. Our old biology teacher said his generation used the word "maidenhead".

Our textbook in the birth control class ("Our Bodies, Ourselves") had diagrams of "maidenheads", intact, partially disrupted, and absent, and pointed out that hymens can be torn for any number of non-sexual reasons, such as exercise or hard work. One thinks of all the girls throughout the ages whose lives were ruined upon the pre-marriage "inspection" because they were thought to be "defiled" (i.e., non-virgins). An ignorance of the female body that went along with an ignorant morality.

When I was in high school it was said that horseback riding provided a good excuse for a busted hymen.

Johnson fired Stanton in 1868, and Myers is a 1926 case. Where exactly in the Myers decision does the Supreme Court specifically find that Johnson's firing Stanton was lawful? The one reference to "Stanton" in the Myers decision appears to be in Justice Brandeis's dissent.

See my comment from "Today in Supreme Court History" for October 25, 2022:

Myers v. United States, 272 U.S. 52 (decided October 25, 1926): President can remove officers appointed with consent of Senate (here, a postmaster) without Senate approval, even though Constitution is silent on the issue; striking down 1876 statute and (finally) striking down the Tenure of Office Act under which Andrew Johnson had been impeached

According to Wikipedia, the Tenure of Office Act was formally repealed in 1887, and the Supreme Court's observations about it in the Myers decision were dicta:

The Tenure of Office Act was formally repealed in 1887.

Constitutionality

In 1926, a similar law (though not dealing with Cabinet secretaries) was ruled unconstitutional by the United States Supreme Court in the case of Myers v. United States, which affirmed the ability of the president to remove a Postmaster without Congressional approval. In reaching that decision, the Supreme Court stated in its majority opinion (though in dicta), "that the Tenure of Office Act of 1867, insofar as it attempted to prevent the president from removing executive officers who had been appointed by him by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, was invalid".[3]

Thanks!

I’ll revise my summary for when October 25 rolls around again.