The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Today in Supreme Court History: November 21, 1926

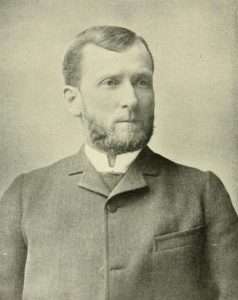

11/21/1926: Justice Joseph McKenna died.

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Bank of Marin v. England, 385 U.S. 99 (decided November 21, 1966): bank which had no notice of bankruptcy proceeding not required to turn over to trustee amounts of checks drawn by bankrupt pre-petition but honored post-petition (everything had been squared away with the payee so at issue was only the imposition of costs)

New York, New Haven & Hartford R.R. Co. v. Henagan, 364 U.S. 441 (decided November 21, 1960): woman stepped in front of train in attempt to commit suicide; train came to sudden stop and waitress in dining car was injured by the jolt (soft tissue injuries plus "paranoid psychosis"). The Court here affirms summary judgment for the railroad. (P.S. Train did not stop in time.)

State of Washington v. Kuykendall, 275 U.S. 207 (decided November 21, 1927): towing of logs across Puget Sound met statutory definition of "common carrier" even if not registered as such and therefore can only charge scheduled rates even though rate for this job was set by contract between it and private party

In 1987 a man sat on train tracks near a military base as a protest. A train ran him over, severing his legs. The crew sued him for emotional distress. According to Wikipedia the crew lost because the guy on the tracks didn't expect to be run over.

Suicide by train is if not common at least not rare. I don't know how often lawsuits against suicidal trespassers succeed. Suicide correlates with being judgment-proof. While rich and poor might be despondent for reasons unrelated to station in life, the poor have an additional reason. And people like Richard Cory can afford a gun.

The injured train waitress had prevailed in her initial jury trial. The trial judge denied motions for a new trial and for a judgment notwithstanding the verdict, stating that while he saw no evidence of negligence by the railroad, it was not for him to substitute his opinion for the jury's.

The First Circuit panel unanimously upheld the verdict. 272 F.2d 153 (1st Cir. 1959). The engineer had testified that he had first spotted the woman on the tracks when she was 30-40 feet away and immediately applied the emergency brake. The train travelled some 80 feet before stopping, the shortest distance physics allowed. The plaintiff's claim of negligence was that the engineer should have spotted her sooner.

In upholding the verdict, the court wrote:

Id. at 156.

As captcrisis noted, the Supreme Court reversed the First Circuit in a brief per curiam opinion. Justices Black and Douglas dissented, believing the First Circuit's analysis had been correct. Justice Frankfurter noted that he would not have granted certiorari.

As perhaps an odd postscript to the case, some two weeks after the Supreme Court issued its opinion, Judge Peter Woodbury, who had written the opinion for the First Circuit, was severely injured when the train on which he was a passenger collided with a bottled gas truck. Six people were killed in the accident, including one of Woodbury's clerks. Woodbury would recover and continue to serve on the court until 1964, when he took senior status until his death in 1970.

It occurs to me that even if the engineer had spotted the woman on the tracks a few seconds earlier, thereby applying the emergency brakes a few seconds earlier, that the waitress’ injuries would have presumably been exactly the same.

Plaintiff’s counsel might have callously argued that, realizing the train had no chance to avoid hitting her, it was negligence to apply the brakes at all, but, as the First Circuit noted, he did not make that argument.

Thanks!

I think this is McKenna's most famous opinion (which lasted almost 40 years before being overruled):

https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/236/230/

Allowed movie censorship because movies aren't part of the press.

Once movies were counted as press in the 1950s, the court toyed with the censors for a few years and eventually made a decision imposing strict procedural requirements on the censors. Together with narrowing the definition of obscenity, the censors mostly got the message and closed up shop.

Some censors lingered on for a while, but they were increasingly toothless and irrelevant.

Then the movies survived for some more years...