The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Justice Barrett and Affirmative Action

In Grutter v. Bollinger (2003), Justice O'Connor wrote, "We expect that 25 years from now, the use of racial preferences will no longer be necessary." I never took this sentence--or really anything Justice O'Connor wrote--very seriously. And even if she was serious about that point, no one who joined her majority opinion remains on the Court. Yet, in the New York Times, Justin Driver suggests that the quarter-century countdown may provide affirmative action with a six-year stay of execution. For the reasons Ed Whelan explains, I find this possibility extremely unlikely.

Yet, there was one paragraph in Driver's column that caught my eye. He suggests that Justice Barrett's adopted children may affect her views on affirmative action:

Justice Barrett may also be less reflexively hostile to affirmative action than is widely assumed. Is it at least possible that her experience adopting and raising two Black children has made her more intimately attuned to the ugly persistence of racial discrimination than some of her colleagues? Although this notion may initially sound reductive, sophisticated empirical scholarship has demonstrated that judges who have daughters are more receptive to women's rights claims than judges who have only sons. It would hardly be astonishing if a similar, perhaps subconscious, dynamic applied to jurists with Black children and claims of racial justice. In fact, Prof. Maya Sen, one of the authors of the study on judges and their children, said in an interview that adopting a child may affect a jurist's worldview.

I have made this exact point in several Supreme Court term previews. To my knowledge, Judge Barrett was never called upon to decide any cases involving racial preferences. And, as best as I can recall, her legal scholarship did not touch on this issue. But Barrett did talk about race during her confirmation hearing. She recalled how she discussed George Floyd's death with her children.

"Senator, as you might imagine, given that I have two Black children, that was very, very personal for my family," Barrett told Senate Minority Whip Dick Durbin (D-Ill.), who had asked whether she had seen the video. The judge explained that while her husband had taken her sons on a camping trip that weekend, she and Vivian "wept together in my room" as outrage over Floyd's death mushroomed and consumed the country.

Barrett noted that Floyd's death and the ensuing unrest were also difficult for her 10-year-old daughter, Juliette, who is white.

"I had to try to explain some of this to them," she told the committee. "I mean my children — to this point in their lives — have had the benefit of growing up in a cocoon where they have not yet experienced hatred or violence. And for Vivian to understand that there would be a risk to her brother or the son she might have one day of that kind of brutality has been an ongoing conversation."

I flagged this record in 2021 after Barrett GVR'd a George-Floyd-like case. At the time, I wrote:

Justices are not automatons. These sorts of issues can have a bearing on their rulings. Indeed, I'm not sure that Justice Barrett will vote with the Court's conservative on affirmative action. The 3-3-3 Court is still forming.

Here, Driver seems to echo my point.

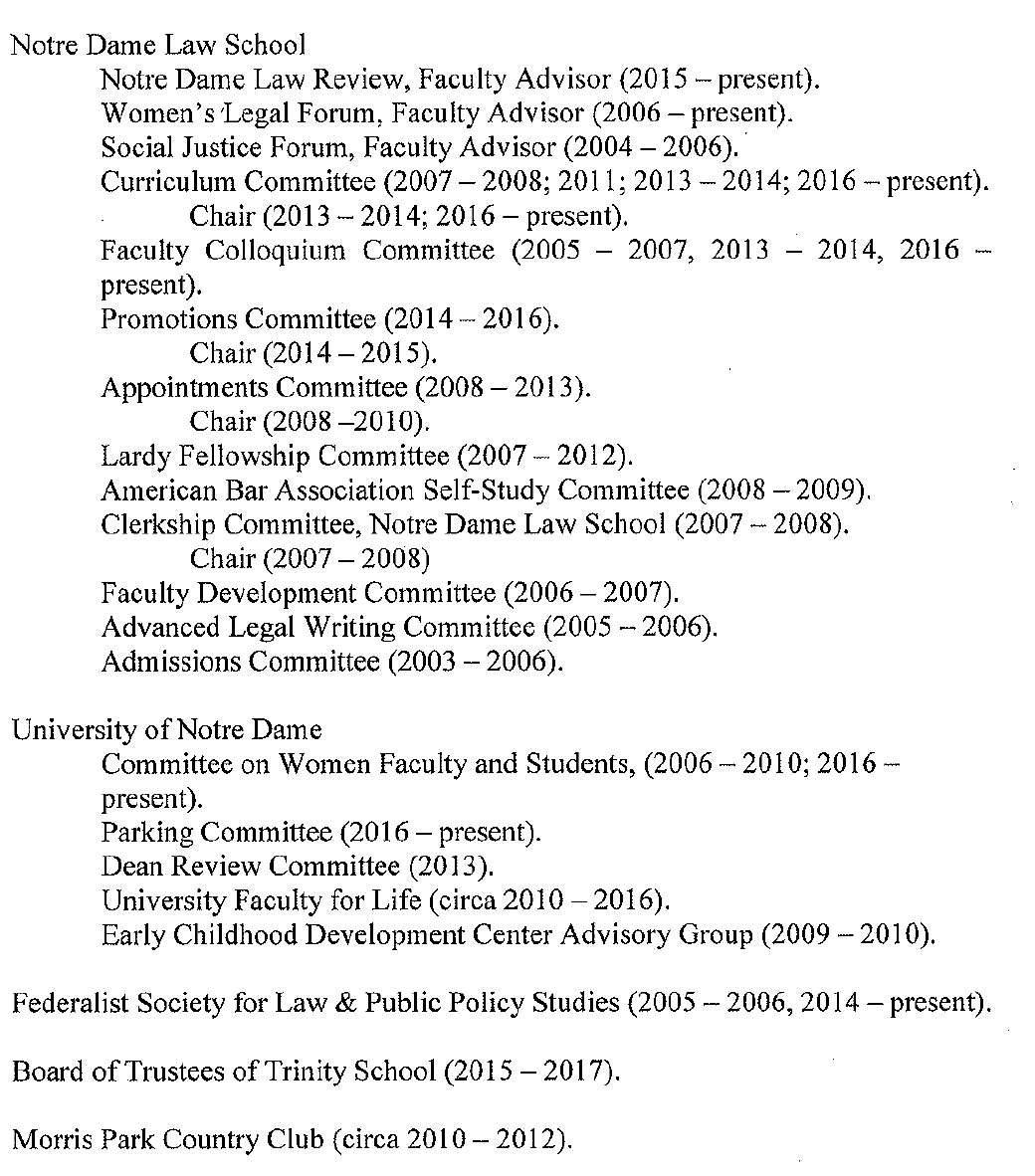

Moreover, Barrett was an academic for a decade. Diversity and inclusion touch every facet of our profession. According to her Senate Judiciary Committee questionnaire, during her time at Notre Dame, she served on the Admissions Committee from 2003-2006. No doubt she gained some insights into how racial preferences operate in higher education. (I served on the Admissions Committee once, and only once, due to my views on affirmative action.)

Barrett's views on Students for Fair Admission may be affected by her personal experiences. Don't presume she lines up with Clarence Thomas.

Now is it proper for me and Driver to draw these inferences? To be sure, we are not acting on any inside information, other than Barrett's public statements and her well-known personal story. But much of what Supreme Court pundits do is amateur psychoanalysis. We take bits and pieces of data that we know, and use that information to make predictions about how a Justice will decide a case. That process can also be retrospective as well. We take bits and pieces of data that we know to explain why a Justice decided a case the way he did.

Short of having a sit-down with a Justice, or reviewing their papers, we are stuck with the written opinion. To fill this void, punditry speculates. Take it for what you paid.

Show Comments (82)