The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

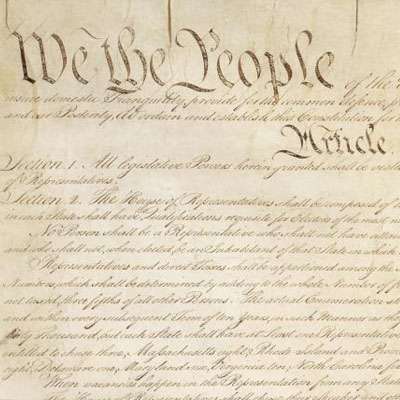

Today in Supreme Court History: September 17, 1787

9/17/1787: The Constitution is signed.

Happy Constitution Day!

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Mikutaitis v. United States, 478 U.S. 1306 (decided September 17, 1986): Stevens grants stay of contempt order of witness who refused to testify in denaturalization proceeding against Nazi collaborator despite being given immunity; witness had also collaborated but had also aided Lithuanians trying to break away from the Soviet Union (our ally at the time), and argued that sealing of testimony would not protect him because he himself was in danger of being deported to the Soviet Union where he would be convicted of treason and executed; Stevens notes that whether sealing is adequate to protect witness is an open question that is subject to another pending cert application (though cert in both cases was denied the next month) (did Stevens really think the Soviets, no sticklers as to rules of evidence, would have to see the transcript? all they had to do to convict him of treason would be to read Stevens's discussion of the facts) (unknown what happened to Mikutaitis)

Twelve states appointed 70 delegates to the 1787 Constitutional Convention. (Rhode Island did not send any.) 55 delegates actually showed up to the convention, some having declined their appointments or being unable to attend for various reasons. 41 made it to the end, and 38 of those signed the Constitution.

Four signers of the Constitution would go on to serve on the Supreme Court: William Paterson of New Jersey, James Wilson of Pennsylvania, John Rutledge of South Carolina, and John Blair of Virginia. Connecticut delegate and future Chief Justice Oliver Ellsworth left the convention early for business reasons, but would write in support of ratification. Maryland appointed furure Justice Gabriel Duvall a delegate to the convention, but he declined the appointment. Likewise, Robert Harrison another Maryland appointee who declined his appointment, would be nominated to the Supreme Court by President Washington and confirmed by the Senate, but would decline the appointment for health reasons. (Harrison would pass away a little more than six months after declining his appointment to the Supreme Court).

I would have loved to have been a fly on the wall for that Convention. In fact we all would.

Yes, we all would have learned something about reasoned debate, where for the most part respect was shown for differing opinions.

Well, that is an idealized version of the past.

True. But in secret, off the record proceedings, with no crowd to play to, and among men who have been through a lot together, there might have been a different dynamic.

I certainly agree 100%. I’m glad we have a few notes of the convention, but wish there were more. Imagine if we had had video coverage! (Though that likely would have altered outcomes in unpredictable, unknowable ways.)

Could one say that the first 150 +/- years after the ratification of the Constitution was a period of correcting many of its errors? highlights include:

The lack of specifically defined rights was corrected by the Bill of Rights

Flaws in the method of electing Presidents by the 12th

Slavery abolished by the 13th

Women allowed to vote by the 19th.

I mention these because it was obviously a flawed document.

I ask for your input to determine what others here believe are flaws which still exists with the document, even as amended.

I see a few such as:

1) The failure to separate the roles of head of state and government

2) The above failure leads to the politicization of all presidential appointments and nominations, especially the judiciary

3) No time limits on declarations of war

4) Unlimited power of taxation and borrowing

5) Creating a presidential system of government

6) The transfer of power from the states into the hands of the central government creating an imbalance in the opposite direction than the imbalance favoring the states that existed under the Articles

Which of your "errors" would have been recognized as such at the time? Slavery was a deliberate compromise. Presidential election was a mistake. There was nothing in the constitution preventing women from voting.

In reading the anti-Federalist writings, it is clear many of these were observed and addressed during the ratification debates. Most notably, the anti-Federalists recognized the unlimited power of taxation, the warmaking powers and the power shift away from the states as presenting a danger to liberties.

I cannot recall how the question of a presidential system of government was addressed. Like other errors, such as slavery which were later addressed as people came to realize how evil that practice was, the error of presidentialism can and should be addressed.

Watching coverage of the queue waiting to pay respects to the Queen, I’m reminded of the difference between their Constitution and ours. Theirs, unwritten, developed over centuries, is based on what has been shown to work. Ours, written, is based on what men in 1787 thought might work.

Yes, freedom of speech is so much better protected in the UK.

Democracy depends on freedom of speech, and their democracy functions pretty well, compared to ours.

The men who wrote our Constitution lived under the unwritten English constitution and saw first hand what didn't work and sought to (as best they were able) to craft something better.

Not true. They tried to imitate the British system to the extent they could.

Something is not true because of your say so.

Draw some examples of imitation.

Bicameral legislature with each house having different powers

Legislature consisting of constituencies of different population

Democracy (kind of)

An executive with limited powers

A judiciary using common law plus statutes

. . . to begin with

-Upper house accountable (indirectly) to the people.

-Chief executive/head of state subject to election (which ended up being direct election)

-Acts of national legislature only supreme if made in pursuance of a written constitution

-The written constitution itself

-Members of executive couldn't serve in legislature

-Executive tenure not dependent on having a politically-sympathetic legislature

-no titles of nobility

-did I miss anything?

Those were unavoidable deviations. In 1787 they had no monarch, no ancestral landed aristocracy (House of Lords), no political parties (no one to pick a Prime Minister), and of course no centuries old tradition providing an unwritten set of rules.

"And what have we wrought?"

"A Republic - if you can keep it!"

I'm not so sure now.