The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

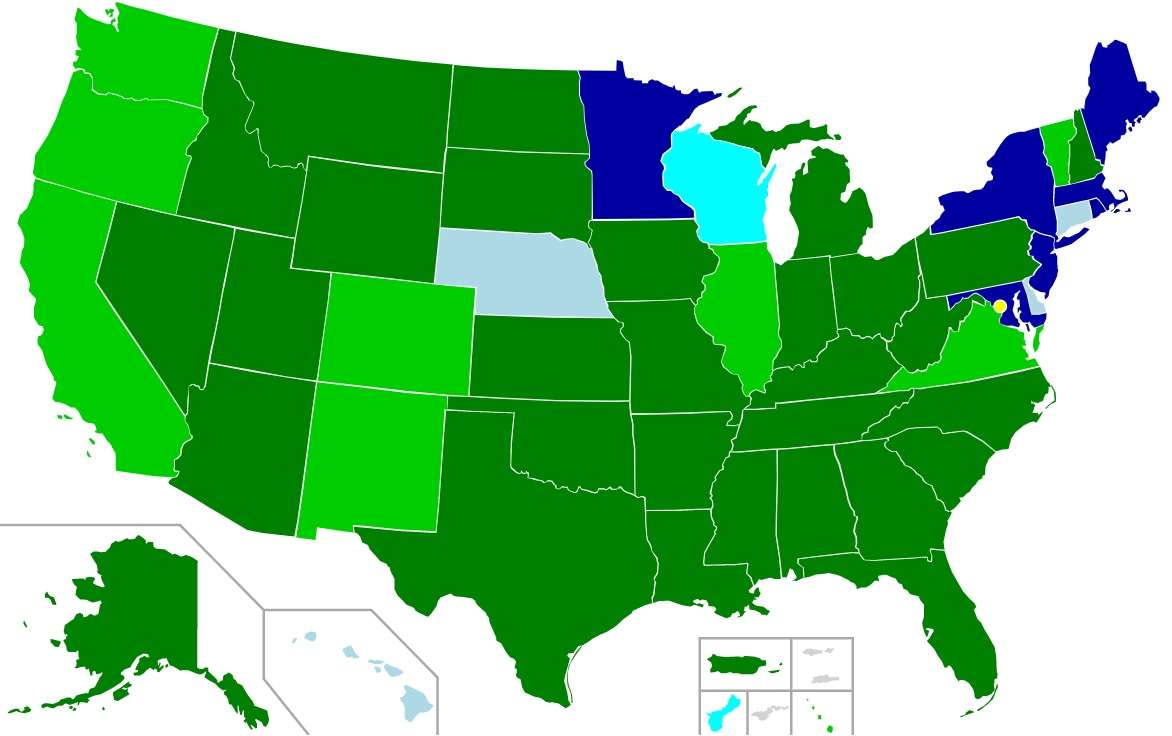

3/4 of States Are Now Stand Your Ground; only 12 Are Duty to Retreat

But what exactly do these terms mean?

I wrote about this several months ago, but several states have gone stand-your-ground since then—Ohio, Arkansas, and now North Dakota—so I thought I'd repeat it. [UPDATE: For more about a twist on the duty to retreat, the duty to comply with negative demands, see this follow-up post.]

[A.] The "duty to retreat" is something of a misnomer (though a very common one); it's not actually a legally binding duty (the way a parent has a duty to support a minor child, or a driver has a duty to exercise reasonable care while driving). Rather, it's a provision that, under certain circumstances, failing to retreat from a confrontation will effectively strip you of your right to use deadly force for self-defense.

To see how it works, let's first set aside situations where you may not use deadly force for self-defense regardless of whether you're in a stand your ground state:

- You generally can't use deadly force for self-defense in most states unless you reasonably believe that you're facing the risk of death or serious bodily injury or some serious crime: rape, kidnapping or, in some states, robbery, burglary, or arson.

- In particular, you can't use deadly force purely in retaliation, once any threat has passed.

- Nor can you use deadly force against a simple assault, unless you reasonably believe that you're facing the risk of death or serious bodily injury.

- You often can't use deadly force merely to protect property, but it's complicated.

- You generally can't use deadly force where you are yourself engaged in the commission of a crime (e.g., if you're robbing someone and he fights back, you can't "defend" yourself against him).

- You generally can't use deadly force if you attacked the victim or deliberately provoked the victim with the specific purpose of getting the victim to attack or threaten you.

Now let's set aside situations where you may use deadly force for self-defense, again regardless of whether you're in a stand your ground state:

- You reasonably believe that you're facing the risk of death etc. (see above) and you can't retreat with complete safety. This would cover most situations where, for instance, you're facing an attacker who has a gun, since one generally can't safely retreat from a gun.

- You reasonably believe that you're facing the risk of death etc. and you're in your home, or (in some states) on other property that you own or in your vehicle or in your workplace. At least the "home" aspect of this is often called the Castle Doctrine, on the theory that your home is your castle.

So what does that leave for the duty-to-retreat / stand-your-ground debate?

- You reasonably believe that you're facing the risk of death etc.

- You're outside your home (or similar place).

- You're not committing a crime, and you aren't the initial aggressor, and (generally speaking) you are where you are legally entitled to be.

- In duty-to-retreat states, you are not legally allowed to use deadly force to defend himself if the jury concludes that you could have safely avoided the risk of death or serious bodily injury (or the other relevant crimes) by retreating with complete safety.

- In stand-your-ground states, you are legally allowed to use deadly force to defend yourself, regardless of whether the jury concludes that you could have safely avoided the risk of death etc. by retreating.

As best I can tell, the current rule is that 12 states fall in the duty to retreat category, with the states being bunched up quite a bit geographically; the other 38 states are stand your ground:

▮ Stand your ground by statute (30 states plus PR)

▮ Stand your ground by court decision (8 states plus CNMI)

▮ Duty to retreat except in your home (MA, MD, ME, MN, NJ, NY, RI)

▮ Duty to retreat except in your home or workplace (CT, DE, HI, NE)

▮ Duty to retreat except in your home or vehicle or workplace (WI, GU)

▮ Middle-ground approach (DC)

▮ No settled rule (AS, VI)

Pennsylvania imposes a duty to retreat only when faced with an attacker who isn't displaying or using a weapon "readily or apparently capable of lethal use." Since it's rare to have a threat of death or serious bodily injury (remember, you generally can't use deadly force without such a threat) in the absence of such weapons, or of physical restraint that prevents a safe retreat, I view the Pennsylvania rule as being more on the stand-your-ground side.

The rule in federal cases seems to be ambiguous, and it is in D.C. as well. The D.C. formulation, for instance, is a "middle ground." The law "imposes no duty to retreat, as it recognizes that, when faced with a real or apparent threat of serious bodily harm or death itself, the average person lacks the ability to reason in a restrained manner how best to save himself and whether it is safe to retreat." But it "does permit the jury to consider whether a defendant, if he safely could have avoided further encounter by stepping back or walking away, was actually or apparently in imminent danger of bodily harm." Query what exactly that means.

Still, I think this reflects the general pattern:

- 3/4 of the states are stand-your-ground, and most of them took this view even before the recent spate of "stand your ground" statutes.

- There is however a significant minority, basically a quarter of the states, in favor of a duty to retreat.

- Of course, none of this tells us what the right rule ought to be.

Show Comments (284)