The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Exclusionary Zoning is Even Worse than Previously Thought

Fixing a calculation error in a leading academic article on the subject shows that zoning has a far bigger negative impact on the economy than was previously realized.

Economists and land-use scholars across the political spectrum have long known that restrictive zoning cuts off millions of people from housing and job opportunities. It is one of the biggest obstacles to increasing economic growth and promoting opportunity for the poor and disadvantaged. But new evidence suggests that the problem is even worse than previously thought.

The work of economists Chang-Tai Hsieh and Enrico Moretti is perhaps the most influential in the literature documenting the impact of zoning on economic growth. Recently, my George Mason University colleague, economist Bryan Caplan, discovered some significant calculation errors in their pathbreaking 2019 article "Housing Constraints and Spatial Misallocation." Hsieh and Moretti have graciously acknowledged the mistake.

When scholars err, the effect is often to make their arguments seem stronger or better-supported than is actually the case. In this instance, however, Hsieh and Moretti's mistake actually made the harmful effects of zoning seem much smaller than is actually the case. Bryan explains:

Where did HM go wrong? On pp.25-6 of their article, they write:

Starting with perfect mobility, the second row in Table 4 shows the effect of changing the housing supply regulation only in New York, San Jose, and San Francisco to that in the median US city. This would increase the growth rate of aggregate output from 0.795 percent to 1.49 percent per year—an 87 percent increase (column 1). The net effect is that US GDP in 2009 would be 8.9 percent higher under this counterfactual, which translates into an additional $8,775 in average wages for all workers.

On the next page, they re-estimate the results with imperfect mobility:

Table 5 shows that changing the housing supply regulation in New York, San Jose, and San Francisco to that in the median US city would increase the growth rate of aggregate output by 36.3 percent (second row). The net effect is that US GDP in 2009 would be 3.7 percent higher under this counterfactual, which translates into an additional $3,685 in average wages for all workers, or an increase of $0.53 trillion in the wage bill.

Both tables indicate that HM are covering the period from 1964-2009. How then can these enormous changes in the annual growth rate, compounded over 45 years, lead to relatively modest changes in total GDP? Answer: They can't!

The correct estimate to derive from Table 4 is that GDP will be 1.0149^45/1.00795^45=+36% higher, not +8.9%.

Similarly, the correct estimate to derive from Table 5 is that growth will be 1.084% per year (.795%*1.363), so GDP will be 1.0108^45/1.00795=+14% higher, not +3.7%.

Bryan also describes some similar mistakes elsewhere in the article.

The upshot of all of them is that restrictive zoning reduces GDP several times more than Hsieh and Moretti's original calculations imply. And, I would add that a high percentage of that loss falls on the poor and disadvantaged (who are, for obvious reasons, disproportionately represented among those priced out of desirable housing markets and the jobs available there, as a result of artificial supply constraints imposed by zoning).

I cite some of the earlier Hsieh-Moretti estimates in my own work, including Chapter 2 of my book Free to Move: Foot Voting, Migration, and Political Freedom. I plan to update as as soon as I get the chance!

All of us who work on these issues owe a debt to Bryan Caplan for discovering this problem in the data, and bringing it to our attention. At least in the United States, exclusionary zoning is the biggest property rights issue of our time. It severely constricts the rights of millions of property owners. It is also one of the biggest obstacles to increasing economic growth and alleviating poverty.

Bryan's discovery shows the latter aspect of the issue is even worse than we thought. He is now working on a book about housing and zoning, which I look forward to with great interest.

In recent years, there has been important progress on reducing zoning in several parts of the country. The Biden administration has included some useful incentives for state and local governments to cut back on zoning in its otherwise mostly awful infrastructure bill. But much, much more needs to be done.

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

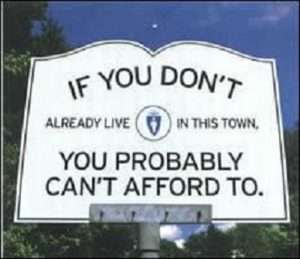

That sign was typical in New England, especially CT

Hi, Ilya. You still refuse to provide your home address. I want to take your neighboring houses and fill them to the max with Democrats. For example, your 3 bedroom house next door will find 2 dozens illegals who would love to move there. They would fit in easily. This will markedly increase economic activity in your street. What do you have against the manufacture of drugs, the sale of drugs, the sex workers. The economic output of your street would soar to $10 million a year.

Do you have children, Ilya? They can be taught about white fragility, as your neighbors elect a new School Board. They need to learn to accept getting accosted by the neighbors.

Hi, Ilya, aren't you an Ivy indoctrinated lawyer? The home address or STFU.

You, sir, are an idiot. I've never seen so many strawmen in my life.

Hi, Friendly. What you call straw men are solid Democrat agenda. They are moving Democrats into neighborhoods. They are decriminalizing crimes by the bucketful to empower and to enrich Democrats. You're an economist. If i seize the orher 5 houses on Ilya's block, fill them with illegals, set up drug labs, and escort sevices, you don't think I could raise the economic productivity of the street to $10 million a year? That is a lot more enhancement than the 2% in the article.

Ilya, an Ivy indoctrinated lawyer is too good to debate a civilian. A dumbass economist has to defend him. Economist, another toxic garbsge occupation. You can predict effects that go in a straight line. But nothing goes in a straight line. Then almost all economists are Commie traitors. You suck professionaly.

Friendly, when you move Democrats in, the place becomes a shithole, no exception. That an absolute law of economics. Even very rich Democrat places are shitholes, an immutable law of economics.

Wow, Davi. You make foaming at the mouth seem like normal calm behavior in comparison

Try being more lawyerly. That term is a sincere compliment is my book.

As someone much less wedge shaped -- and a dull wedge, at that -- than the man who can't spell his own name once observed, you can't pet a rabid dog.

Democrats and liberals *love* zoning power, you savage ignoramus. Zoning started in the Progressive Era.

People who deny the genotype of every human cell in their body do not have credibility.

"do not have credibility"

As opposed to ignorant tossers.

No; he's a mentally ill racist.

You're a literal maniac. I hope you get help soon.

Ilya is by far the worst blogger on this site. He writes constant unbalanced crap, and never bothers to respond to any criticisms. He's a poster example as to why immigration should have been halted permanently. Because the children of immigrants are never able to think clearly on this, and support further immigration to the point where it destroys America.

"Because the children of immigrants are never able to think clearly on this"

Do you have a working synapse?

Wow, I've never lived up North and have never seen a sign like that. Interesting to know it's actually a thing, I thought it was a made up meme Ilya found to illustrate his point...

It's a parody of the official Massachusetts town line sign, which usually has the name of the municipality and the year it was founded.

EG: https://external-content.duckduckgo.com/iu/?u=https%3A%2F%2Ftse1.mm.bing.net%2Fth%3Fid%3DOIP.67L98bNpWisqaiogU_JekwHaEy%26pid%3DApi&f=1

I've never seen such a sign, but I've driven through Litchfield, CT and imagined it there. You don't really (literally, as Tucker Carlson might say) need a sign.

The question never asked in these grand social engineering feats is is the maneuvering of ppl advantages to all. Yes, having a cheapo 3 story apartment building next to a 1 acre single family home is good for the the apartment dwellers and good for the government (oh boy, more tax revenue), but what does it do to the quality of life for that single family resident. And shouldn’t they have a choice, or a right not to associate. Ppl are not lab rats, and decisions are how/with whom to live (similar to whom they sleep with) and the lifestyle they desire should be based upon their decisions. They are best able to weigh the advantages/disadvantages to them and make a choice. Some opt for more room and commute. Others value proximity to cultural centers and stack up in the cities. Bottom line, people’s priorities may be vastly different than the government or the SJWs. And because were in America, not Russia/China/Cuba, the choice should be theirs.

Maybe you didn't notice, but the democrats won the elections.

Democrats cheated and stole the election. Biden is not my President.

Get over it, dumb ass. Your idiot of a candidate lost decisively because he is, as Rex said, a fucking moron.

A libertarian defending government dictating what people can do with private property? How novel.

You mean Ilya Somin defending the federal government dictating zoning laws nationwide?

*Zoning* is grand social engineering, it's the government stepping into the market and private property owners decisions and telling them 'no, we have to do what's best for the community writ large.' Your bigotry is blinding you to first principles.

Houston famously has no zoning, but much of new construction has homeowner associations that give much of the same function. It's been said that the only thing worse than an HOA is not having an HOA when you need one (they are like lawyers in that regard).

You realistically need some coordination about how a city is arranged with commercial, residential, and industrial zones. Don't confuse the concept of zoning with the fact that it's often done badly.

While it may be better overall with no zoning the reality on the ground is it makes for a terrible place to live. Visit Houston if you want a good example. It's why many people moved outside of Harris county to get away from the nonsense. Yeah sure Kirkland will post an obnoxious screed that it's white flight or some bullshit but it's not just white people leaving the stank of Houston for greener pastures and peace of mind.

No surprise to see this guy going all in on casual authoritarianism.

I live in Houston and am in the process of selling what would be a tear-down in a non-historic district (it's in a historic district which has no history). White peope are lining up.

Houston is famous for not having land use rules. (But, Shoup points out, they still have minimum parking requirements.) Zoning to separate residential and industrial uses prevents some negative externalities that may be hard to to quantify. There would be some value in separating analysis of that kind of zoning from lot size rules and multi-family bans. For example, what if my 2 acre zoned neighborhood were changed to 1 acre? Residents would be worse off, but newcomers would be better off.

How would the residents be worse off? They would still own their two acre lots.

It's the relative neighborhood density. Many times residents prefer lower levels of neighborhood density.

On a larger note, home and home prices are about more than just the land itself. It's about where the land is, what it borders, who it borders, and so on. It's about the "neighborhood".

Have a house on a two acre lot, surrounded by other houses on two acre lots...that's one thing. Have a house on a two acre lot, surrounded by apartment buildings. That's something else entirely. It changes the character of the neighborhood.

Right. I wanted a house in the woods and I paid extra for it. If the number of houses around me doubled the value of my house to me would decrease.

Some people own oversize lots to keep density even lower. I know one owner who was willing to sell half of her 4 acres on the condition that the buyer not build too close to her house. No deal. Another oversize lot near me isn't owned by a resident and is likely to be built up to the maximum density allowed by law. Too bad for us but that's how property rights work.

Buy the land you want to control, don't try to get the government to assert control for you.

Obviously there are some legitimate land use restrictions on density, such as where wildfires, lahars, or tsunamis are endemic and constraints on road building would prevent enough capacity to evacuate it in an emergency.

To a certain extent, government is just a group of people getting together to decide on common rules and regulations, in order to avoid tragedy of the commons type situations.

"Many times residents prefer lower levels of neighborhood density."

If all the lots are owned by residents already there won't be a density change.

Unless of course some of the residents sell half their lots. In which case, those residents obviously considered themselves better off with the money than with living in a lower density neighborhood.

Nobody lives forever. When it comes time to move or die the decision to subdivide will be made by nonresidents. A buildable lot in my neighborhood is owned by a nonprofit which needs money more than land. The board of directors has a duty to maximize value. So they will build whatever they can get permits for, or more likely sell it for $1.5 million to a developer who will build $6 million worth of houses to get a good return on investment. (See comment below on opportunity cost.)

There's a bit of a tragedy of the commons problem here though.

Pretend for a second, in a lot of 50 houses on 2 acre lots. That's a density of 1 family for every 2 acres for the neighborhood. Or an inverse density of 2.0.

Assume a family is willing to pay a premium of $10,000 per acre of inverse density in the neighborhood. Or $20,000 per house to start

The first family to split their property in 1/2 and sell both makes $39,200. (51 houses total). The next neighbor $38,400 (52 houses total) The third neighbor splits their property into quarters and makes $71,000 (55 houses total). The 4th neighbor splits their property into 8ths (62 houses total) and makes $129,000.

Until you have tinier and tiner plots, where each house sits on 1/10th of an acre.

I can give you a real life example in Houston. Start out with a 50' X 100' lot with a tear-down worthy bungalow on it which sells for $200,000. Divide it by four, and build four "townhouses" on the 50'X100' lot. Each is currently appraised by the county at about $400,000. That's about $1.6 million with about $500,000 of that being lot value and $1.1 million in improvements. Or, around the corner from that you have a disgusting duplex which the owner sells for $129,000 because he can't scrape up the cash to make the tax payment. Currently there are two "townhouses" on that 50'X100' lot one of which is for sale for about $800,000.

One good sized apartment building can house enough voters to outnumber all the people living in single family houses, and the next thing you know, the local government is hostile to single family housing.

The Bellmore theory of democracy.

People who live in apartments shouldn't count as much as thise who live in single-family housing.

Actually just a part of the overall theory - the denser the population the less their votes should count.

I'd just prefer that apartment dwellers and single family home dwellers, who have distinct interests, live under different jurisdictions.

" Zoning to separate residential and industrial uses prevents some negative externalities that may be hard to to quantify."

It also prevents some positive externalities, that I presently enjoy. I live in a suburban neighborhood, and can walk to the market to buy some groceries, because the market in question was grandfathered in.

I know a builder who wanted to use his state's affordable housing law to build a mixed use development with residences above or behind businesses. The town insisted on 100% residential. The town got small residential units generating low property tax revenue. With no sidewalks most people are going to drive the half mile to the grocery store.

It can. It depends on the zoning laws, and what people choose. Many areas choose to have zoning for light commercial areas within walking distance.

Right. There's a big difference between having a grocery store/hardware store/laundry/restaurant a block or two away and having a factory there.

Right, I'm saying that just because zoning CAN be stupid, doesn't mean it has to be. Mixed use tends to work out quite well, if done intelligently.

The real property rights problems come up with changes to zoning, where reliance interests are violated, and property ends up devalued. For instance, there's a residential street a few minutes walk from here, that the city up and rezoned commercial, in keeping with their long term plans. Now a whole bunch of nice houses are going vacant as their owners move, (In an area that's seeing a major influx of people, yet!) and falling into disrepair, because there aren't really a lot of businesses that are well suited to running out of a single family home.

The owners lost a lot on the deal, because their property could no longer be lived in by new owners, who instead would face the cost of clearing the property. And the character of the neighborhood is now changing.

And it was all so stupid, because we have unused commercial property not very far away, which is where the businesses are actually building.

In the states where I have spent most of my life existing uses are grandfathered when zoning laws change. Suppose I own a sex toy shop in a mixed use district. The city rezones my lot residential to purify the neighborhood. I can remain in business and even sell the business to a new owner. What I can't do is make the use more nonconforming. If my town increases residential lot size to 4 acres my house would be protected as an existing nonconforming use. I could rebuild it if it burned down. I might not be allowed to expand it because that would increase nonconformity.

You ignore the residents who choose to sell in the new 2 acre market.

I don't say this lightly -- Ilya is a thief.

Ilya thinks it is OK to *steal* value from property owners so as to advocate his footloose immigration policy. Well, by the same token, those property owners have every moral right to SHOOT minorities so as to increase the value of their property rights.

I'll bet that Ilya hasn't thought about that one...

... But I suggest he does....

O look it's Ed threatening violence by proxy if someone doesn't agree with him.

You just may be the biggest loser on here.

Bravo!

"By the same token" is not a threat.

Instead it means "on the same grounds," or "for the same reason."

No, Ed.

Prof. Somin never advocates for political violence. And yet somehow you stumble your way into political violence.

Just like you do on a daily basis on almost any issue that comes up here.

You say you hope it doesn't happen, and yet it's your go-to result of every policy you don't like.

You think those that agree with you into political violence, and you advertise such. Not the sign of someone winning any arguments.

But certainly the sign of a loser.

Are you familiar with the rise of the "Know Nothing" movement in the 19th Century and then the Klan about 100 years ago?

Ever hear the expression that those who fail to learn from history get to relive it???

"those who fail to learn from history get to relive it"

One hopes that we learned from the failure of reconstruction following the Civil War. If your lot goes to war and loses, which it will if war occurs, our side will not be so forgiving this time around. The trees will bear strange fruit again, but this time of a different color.

Your argument seems to require that we should have kept Jim Crow out of fear of the Klan.

One does not avoid doing good things out of fear of violent assholes.

Again, the argument of a loser.

It's you who are stealing value Ed, by using the government to infringe on the ownership rights of land you don't own.

You haven't the faintest idea what law is, do you? You cannot sue for loss of property value, the same way you can't Ford can't sue Toyota because they make a better car for cheaper. This is one of the first principles of common law. Damnum absque injuria is not a grounds for tort.

Doctor. I was going to Europe for the summer, for 2 months. I subleased my room to a black kid from the U of Penn. He calls me, 2 weeks later, cancelling. I do not know how they did this, but he was told his ass would be kicked if he took my room, in Center City Philly. He had dropped by the house for 10 minutes to look at it, and to discuss the deal.

This is as moronic as it is immoral.

Under Ed's authoritarian wet dream the government should be doing something like this: if I have two acres and want to give my son and his family one to build a house on the government can and should step in with force to prevent that to protect the 'value of the community.'

I live in a relatively low density area (a Los Angeles suburb) because that's the kind of neighborhood that I want to live in. It isn't so much "if you don't live here you can't afford to", as it is "this town is full; you can't add any more housing".

Prof Somin's writing suggests that growth is good. I submit that growth is good *until* you reach the desired density, and that any growth over that is *bad*.

What's the desired density? Depends on the person, of course, but I'm sure that everybody has a limit. My limit is about a quarter acre per single-family house; anything more than that is too dense and I wouldn't consider living in the area.

The desired density is whatever the market will bear.

So people have no input into what type of community they wish to live in? Developers can just come in and build whatever they want? Your position seems extreme, there needs to be a middle ground and that would include some zoning.

The market *is* people's input.

People with money.

Which is pretty much everybody. That's why it is "money".

The government needs to use coercion to police 'growth' now. Jesus.

Of course. Government needs to use coercion to enforce all laws, doesn't it?

Not laws. Rather, its own rules--legislation. Laws, good or bad, tend to have their own enforcement mechanisms, sometimes counter to and dominant over the imposed legislation regime.

I don't see how the distinction you are trying to make has any relevance to this topic. If you or I violate some rules-legislation, the result will probably be some government coercion. Just like if we violate a law.

"Government needs to use coercion to enforce all laws, doesn’t it?"

The relevance is in the answer to your question, which is an emphatic "No." Not only does it usually not enforce laws, it also does not need to impose legislation.

Yes, enforcement of its rules is what it does, just like robbery is what a bankrobber does. But dismissing any judgment of its actions as a "need" implies an amorallity I doubt you intended.

If Sue employs brute force to make Dan obey, you can only judge her actions based on whether or not Dan did something severe enough to actually deserve such an assault, not based on what emblem Sue wears on her shirt. Law, not legislation, is how such judgements manifest.

The government through overwhelming force very very often successfully grants itself license to violate law. But it does not make the law. We may acquiesce under its power, but we shouldn't withhold judgment--i.e., we shouldn't withhold recognizing the law.

"My limit is about a quarter acre per single-family house; anything more than that is too dense and I wouldn’t consider living in the area."

If your neighbors are willing to sell half their lots to developers, then clearly they have a different view of the desired density than you do.

Why should you be able to use government force to prevent them from doing so?

Isn't that one of the reasons government exists, to settle disputes between people? Why should the neighbors get to determine the proper population density?

1. Zoning rules are not a dispute resolution process.

2. If one neighbor out of dozens sub divides their lot, that doesn't create a significant change in population density. if 80% of the residents want to subdivide, why should the minority control?

3 "Why should the neighbors get to determine the proper population density?" Why should people who don't even live in that neighborhood get to decide the proper population density? That's what is going to happen when you do it through zoning rules.

1. They are if the dispute is specifically about what can be done with certain tracts of land, as in your hypo.

2. I don't think the minority should control, in that case. That would be a good example of zoning gone awry.

3. Actually without zoning, that is what happens. Some developer who doesn't even live in the state gets to decide what happens to the land, and the people who actually live there get no say. With zoning, we get a say through our local and county government, just like with every other issue.

I agree. And when federal or state governments step in and dictate things based on their fully loony ideas and deep pockets, what you get is a really bad case of people who actually live there getting no say.

If one believes as MatthewSlyfield that property owners ought to be able to do whatever they want with their property, that's a perfectly fine argument. But the people you need to convince are the members of that local community in question. Anything else is just being guilty of using an even bigger cudgel of government force or coercion.

No. You're making a category error. The federal or state governments telling a local government that it can't do something isn't "coercion," because local governments don't have rights; only people do.

What is all the real estate in Georgetown worth today? What would it have been worth if residents had not driven out the Hopfenmaier rendering plant—which had escaped zoning with a grandfather privilege? That plant blighted Georgetown—pretty much all of it—for nearly a century. It did that as a non-conforming use. By depressing value in defiance of zoning, the plant's awful presence proved vividly how zoning can increase value by excluding blight.

Many of the property owners enriched when the plant left were black families who owned fairly-valued Georgetown real estate—which is to say real estate with dismal fair market value with the rendering plant in place. Which became real estate with extravagant fair market value with the rendering plant gone.

Why oppose that kind of enrichment for property owners of ordinary means? Why threaten impoverishment on that scale for existing property owners vulnerable to the establishment of some similarly baleful nuisance.

Perhaps zoning does come with costs. That is not the entire ledger. Folks who want to claim zoning imposes costs are not forthright if they do not do a full accounting, and include also in their reckoning both the value which zoning creates, and the value which zoning protects from heedless destruction.

The solution would've been to tax the rendering plant for the emissions it emits. Furthermore, no one is advocating for getting rid of industrial zoning. Merely loosening the ridiculous single-family zoning requirements. Hell, you really want to help those black families? Let them sell their land to real estate developers who without the burden of zoning will pay millions to buy that land and build apartments on it.

Ilya and Friendly, wanna help Democrats out of poverty? Drop their bastardy rates. Leave other people alone you Commie geniuses.

Wow, it's clear the anti-immigration drive on the Right, including the libertarian Right, is shifting once dearly held principles in tectonic plate fashion. Now property rights and markets are down, government power to ensure 'quality of life' and 'community protection' (not protecting individual rights and safety, but the actual community as an abstract, valuable thing) is up.

Gotta have big government to keep *those people* out.

I can't speak for libertarians but conservatives haven't changed their views on property rights. We have always respected people's right to own and enjoy their property, but subject to certain restrictions. We have noise ordinances, occupancy limits, maintenance standards, and zoning. You can say that all these are enforced by government coercion but most property owners are content with that because the restrictions allow people to more fully enjoy their property.

I don't think its libertarians shifting. It feels like very few commenters on these boards are actually libertarians.

Well, my first vote was for a libertarian, I helped found a college chapter of the LP back in the 70's, so I've got at least *some" libertarian creds.

But the LP evolved away from me on multiple fronts. It's really hardly recognizable to a 1970's style libertarian. You'd naturally expect that a lot of commenters at a libertarian site would be taking exception to a libertarian movement that would openly hope to throw an election to somebody like Clinton or Biden. Like they were actually more libertarian than Trump?

To be fair, I've evolved a bit, too: I used to be a David Friedman style anarcho-capitalist, but I eventually concluded that anarchism wasn't feasible in the world we live in.

Libertarianism is doing pretty well except in the popular political rhetoric across the right and left. If you went by political speeches, punditry, and news media user comments, you'd think broad public opinion had killed free speech, free markets, free movement, property rights, and common decency.

The rhetoric we hear and read bears little resemblance to the reality that the vast majoirty of people experience most of their lives.

Ok, these people screwed up basic math, but I should totally take their word they their complicated estimates of GDP growth are spot on?

What are you more likely to trust? An admission of calculation error discovered by a third party, or your own wishful thinking?

Somin is nuts if he thinks that rezoning in cities that are considered highly desirable will result in more affordable housing.

I spent some of my career in building and development doing rezoning in Atlanta, inside the perimeter as it is known. You find a likely group of houses on large lots, a single street say. You offer to purchase all the houses at much higher than current market value subject to rezoning. The rezoning effort is aided by motivated sellers.

Once the property is zoned from one to the acre to five to the acre the purchase takes place and you then build 100 houses on a site that once had 20 houses. Sounds perfect for providing more affordable housing, right? Not a chance. Houses that once sold for $200,000 are replaced by houses priced at $700,000 or more. Why is that? Because that's where the profit is. You don't make money selling cheap houses to poor people in sought-after areas. You can make money selling cheap houses but not there. Rezoning in those areas actually decreases the supply of affordable houses.

donojack is right of course. What he points out explains another problematic fact about housing for the poor. No matter how hard you try, you can't get developers to put subsidized or inexpensive housing in rich neighborhoods. Too much lost opportunity cost in doing that.

Rich suburbanites don't even have to resist; there is no threat any developer will try to make it happen. The only way any low-income housing will ever show up in Sausalito, Georgetown, Park Slope, or Cohasset is under a full-on socialist program to take property by eminent domain, and lose money putting the housing there.

The laws of some states exempt projects from zoning rules if they include enough "affordable" housing. In expensive states if you have enough kids you can live there with a six figure family income. The builder may need to face town lawyers with an unlimited budget. Some get built. Some get lawyered to death. I know of one project that spent about 20 years in court.

You just increased the supply 5x from 20 to 100. Net increase in supply will reduce prices home prices somewhere.

I think I finally understand the theme here, the unifying theme behind most of Ilya's posts. It's not open borders, that's a special case of the general rule. Neither is it no zoning, again, a special case.

All social arrangements that rely on enforceable collective agreements must be destroyed.

A nation that doesn't want to be put in a world-wide blender and reduced to a world-wide average in a world that's poor on average? Must be destroyed.

A neighborhood whose character relies on people not being permitted to endlessly subdivide or use their property for any use imaginable? Must be destroyed.

A chess club that wants to remain a chess club in an area where most people want to play bridge? Must be destroyed.

I live in a pleasant suburban neighborhood, that's been stable for over half a century. It's a perfect place to raise kids, it's peaceful, quiet, low crime, everybody here is here because they wanted to live in such a neighborhood, and sought it out. The neighborhood stays nice, because everybody here is in it for the long haul, and keeps their property up, and cooperates in maintaining the character of the neighborhood.

In Ilya's eyes, it's an abomination that must die, burned away by the purifying fire of no collective rules.

The thing is, collective rules can provide real benefits to the people who agree to them. The pleasant suburban neighborhood. The economy that's not part of "a broad global layer of what a Pakistani brickmaker would consider to be prosperity". The club that plays chess though people who'd like to play bridge covet its swanky clubhouse.

I suggest Ilya review Nozick's Anarchy, State, and Utopia. That 'utopia' consisted of a large collection of states that had freedom of exit, but NOT entry, allowing people to seek out communities that were good fits for them, AND for communities to exclude people who weren't good fits to community.

Ilya wants to throw the world in a blender, instead.

"All social arrangements that rely on enforceable collective agreements must be destroyed."

I think you mean 'enforceable government restrictions on property'. Eliminating government control of private property should be a core value of any libertarian, so this isn't exactly surprising or novel.

Sure and the fun part is when, in order to eliminate the small-time "government control" of local municipalities, some so-called "libertarians" will resort to empowering a much bigger, more powerful mechanism of government control, one that never ebbs and only flows, and is accountable to no one.

So you were involved in the libertarian party in the 1970s, but don't have the first clue what libertarianism is? You don't even seem to grasp that your parade of horribles contradict each other.

The chess club, one presumes, is a private organization. Therefore, to Ilya it can remain a chess club regardless of what "most people" want.

Similarly, a residential property is private. Therefore, it can be a house, three houses on a subdivided lot, a multi-family dwelling, or a comic book store, regardless of what most people want.

You don't own the "character of the neighborhood." You only own your piece of land. Someone else, who owns their own piece, has the right to do what they want with it. If you want to maintain the neighborhood's character, then buy the rights to subdivide or redevelop his property from him.

Ilya is just an agent. He intellectually supports changes that will churn real estate for the enrichment of the billionaires that own the media and the Democrat Party. These vicious predators must be stopped.

A New York predator came to town. His proposed projects would lower value by $100000 for each current owner by exploding capacity. I said, he put up skyscrapers in China. There is no way to overcome his legal skills. He will hire the children of the Zoning Board for no show jobs, and we will be done.

I proposed #MeTooing the scumbag. Start a Facebook group and send out emails to all his employees, have you been sexually harassed at this company? We will pay for your story, and help you get legal recourse.

The hideously ugly feminist Democrats in my town shouted me down, and had me kicked out of the community group.

"The hideously ugly feminist Democrats in my town shouted me down, and had me kicked out of the community group."

Probably because you couldn't stop touching yourself.

The NYC predator is a Democrat, and #MeToo does not apply.

So, you're not going to sue yourself for unwanted, nonconsensual touching? Makes me think of Peter Sellers as Strangelove.

The hideously ugly feminist Democrats in my town shouted me down, and had me kicked out of the community group.

Good for them. I only wish we could do the same here.

I wish we could get rid of thr most toxic occupstion, 10 times more toxic than organized crime, to save the nation.

Can someone translate this into English?

Color me skeptical. I don't trust economic models as far as I can throw them, and I won't start just because the conclusion seems logical and agrees with my preconceived opinions.

In the end, I question the base assumption of this study, that the model accurately represents our current situation, much less that it can realistically recreate a counterfactual scenario. It's not like we can check against an alternate universe to see if it's correctly calibrated.