The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Sixth Circuit Strikes Down Transportation Agency's Exclusion on "Political" Ads and Ones That "Scorn or Ridicule"

The case involved an anti-Islam ad; the court reversed its earlier decision in favor of the transportation agency, based on two more recent Supreme Court decisions.

From American Freedom Defensive Initiative v. Suburban Mobility Auth. for Regional Transp. (6th Cir.), written by Sixth Circuit Judge Murphy and joined by Judges Cole and Siler; I think this is analysis is quite correct:

The Free Speech Clause limits the government's power to regulate speech on public property. The government has little leeway to restrict speech in "public forums": properties like parks or streets that are open to speech by tradition or design. It has wider latitude to restrict speech in "nonpublic forums" that have not been opened to debate. Even there, however, speech restrictions must be reasonable and viewpoint neutral. See Minn. Voters All. v. Mansky (2018).

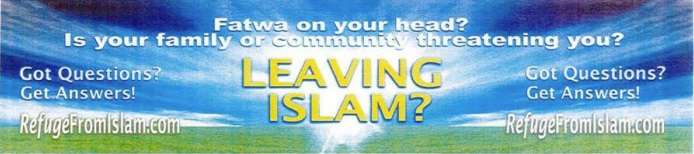

In this case, we must consider how these rules apply to the restrictions that a public-transit authority imposes on parties who seek to display advertisements on its buses. The American Freedom Defense Initiative sought to run an ad that said: "Fatwa on your head? Is your family or community threatening you? Leaving Islam? Got Questions? Get Answers! RefugefromIslam.com." Michigan's Suburban Mobility Authority for Regional Transportation (SMART) rejected this ad under two of its speech restrictions. The first prohibits "political" ads; the second prohibits ads that would hold up a group of people to "scorn or ridicule."

Earlier in this case [in 2012], we found, first, that the advertising space on SMART's buses is a nonpublic forum and, second, that SMART likely could show that its restrictions were reasonable and viewpoint neutral. Since then, the Supreme Court has issued a pair of decisions that compel us to change course on our second conclusion. SMART's ban on "political" ads is unreasonable for the same reason that a state's ban on "political" apparel at polling places is unreasonable: SMART offers no "sensible basis for distinguishing what may come in from what must stay out." Mansky.

Likewise, SMART's ban on ads that engage in "scorn or ridicule" is not viewpoint neutral for the same reason that a ban on trademarks that disparage people is not viewpoint neutral: For any group, "an applicant may [display] a positive or benign [ad] but not a derogatory one." Matal v. Tam (2017). We thus reverse the district court's decision rejecting the First Amendment challenge to these two restrictions….

Speech restrictions in nonpublic forums must be reasonable and viewpoint neutral…. Mansky shows how this test applies to a speech restriction analogous to the one at issue here. That case addressed a Minnesota law that banned voters from wearing "political" apparel at polling places. The Court treated polling places as nonpublic forums. When applying this reasonableness test, it found that Minnesota had pursued permissible ends because the state could reasonably seek to reinforce the solemnity of voting. Voters "reach considered decisions about their government," and states can reasonably conclude that the location of this "weighty civic act" should be free of "partisan discord."

But the Court next held that Minnesota had not used reasonable means to implement these ends because its ban on "political" apparel was not "capable of reasoned application." On its face, the word "political" has no clear meaning. Although it can have a broad reach, Minnesota interpreted it more narrowly to cover only those messages that a reasonable observer would view as related to the electoral choices in a given election. Yet a separate law already banned campaign materials.

This "political" ban thus covered more: things like "issues" on which a candidate had taken a stance or "groups" that had political views. That ambiguous definition, however, "pose[d] riddles that even the State's top lawyers struggle[d] to solve." The lawyers suggested, for example, that a shirt with the Second Amendment's words would be "political," but a shirt with the First Amendment's words would not be. These nonobvious distinctions led the Court to conclude that the "political" ban could not be objectively applied. Instead, the ban gave election judges at each polling place too much "discretion" to decide what qualified as "political." The Court concluded that states "must employ a more discernible approach than the one Minnesota has offered here."

SMART has failed to adopt a "more discernible approach." To be sure, like the law in Mansky, SMART's ban on "political" ads serves "permissible" ends. SMART seeks "to minimize chances of abuse, the appearance of favoritism, and the risk of imposing upon a captive audience[.]" Lehman v. City of Shaker Heights (1974) found similar objectives permissible. Nevertheless, SMART must adopt "objective, workable standards" to achieve its permissible ends. And like the law in Mansky, SMART's speech restriction combines the same "unmoored use of the term 'political'" with the same risk of "haphazard interpretations."

First, SMART cannot rely on its Advertising Guidelines' unadorned use of the word "political" to create workable standards by itself. The word has a range of meanings. It can have an "expansive" reach, covering "anything '[o]f, relating to, or dealing with the structure or affairs of government, politics, or the state.'" SMART, however, does not follow this broad reading. Under this definition, even get-out-the-vote drives or public-service announcements encouraging individuals to report drunk drivers would qualify. Yet SMART allows such public-issue ads.

The word alternatively can have a narrower reach, covering anything "[r]elating to, involving, or characteristic of political parties or politicians: a political campaign." But SMART does not interpret the word this way either….

Second, SMART cannot rely on any official guidance to create workable standards. Apart from its Advertising Guidelines, SMART has no other sources defining the word "political" or telling officials how to apply it….

Third, SMART's made-for-litigation definition of "political" also cannot provide workable standards. When asked to give SMART's official definition, its designee defined the word as "any advocacy of a position of any politicized issue." The designee defined the word "politicized" this way: "[I]f society is fractured on an issue and factions of society have taken up positions on it that are not in agreement, it's politicized." He added that an ad must be "advocacy of one of those viewpoints on the issue." We think that this definition is subject to the same risk of "haphazard interpretations" that Mansky found unacceptable….

[T]he subjective enforcement of an "indeterminate prohibition" increases the "opportunity for abuse" in its application. The First Amendment favors rules over standards because the former make an administrator's job largely ministerial whereas the latter leave room for the administrator to rely on "impermissible factors." And "the danger of censorship and of abridgment of our precious First Amendment freedoms is too great where officials have unbridled discretion over a forum's use." As in Mansky, we do not question that SMART seeks to act in an "evenhanded manner," but it has yet to create the workable standards that it needs for "reasoned application" of its ban….

SMART alternatively rejected AFDI's fatwa ad under a restriction prohibiting ads that could hold a group of people up to "scorn or ridicule." Matal shows that this rationale has a free- speech problem of its own: It discriminates on the basis of viewpoint…. The Court has held that viewpoint discrimination exists even when the government does not target a narrow view on a narrow subject and instead enacts a more general restriction—such as a ban on all "religious" speech or on all "offensive" speech [expressing "ideas that offend"]…. Like the trademark statute prohibiting marks that bring individuals into "disrepute," SMART's restriction prohibits ads that are "likely to hold up to scorn or ridicule any person or group of persons." This restriction necessarily discriminates between viewpoints. For any group, the restriction facially "distinguishes between two opposed sets of ideas": those that promote the group and those that disparage it. Iancu v. Brunetti (2019).

SMART has applied its restriction in the same way. It, for example, has run an ad that promotes attendance at a local church. But the scorn-and-ridicule guideline would compel SMART to ban an ad ridiculing those who attend this church. Similarly, SMART conceded that an ad implying that Islam is a "religion of peace" likely would not violate its scorn-or-ridicule restriction. Yet SMART found that AFDI's ad violated the restriction because it implied that Islam was violent by suggesting that members of the faith would threaten family members. On its face and as applied, therefore, SMART's restriction engages in impermissible viewpoint discrimination….

Like the speech regulations in Mansky and Matal, SMART's two restrictions in this case are "understandable." SMART sells advertising space to generate revenue, not to lose it. And political ads that advocate for positions with which large segments of SMART's customer base disagree or that disparage large segments of that base might well cause some to choose other transit options.

But our response to these concerns can be no different from the Supreme Court's response to them. As the Court made clear in Mansky, SMART must "strike the balance" between protecting its riders' tranquility and its advertisers' expression in a way that permits "reasoned application." And "as the Court made clear in [Matal], a [speech restriction] disfavoring 'ideas that offend' discriminates based on viewpoint, in violation of the First Amendment."

Show Comments (1)