The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Why Ranked-Choice Voting Might Make Little Difference In Heavily Contested Primaries

One advantage of using primaries to select nominees for President is that when the selection process takes place over time, it is easier for similarly-minded voters to coordinate on nominees. Today is a good illustration, as the departures of Pete Buttigieg and Amy Klobuchar from the race for the Democratic nomination facilitate the coordination of moderate Democrats, presumably to the benefit of Joe Biden. Whatever one's politics, it may seem perverse that the more candidates who cluster around a particular set of issue positions, the greater the advantage for candidates outside the cluster. And it may also seem perverse that candidates sometimes must drop out to best address the ideological interests of their supporters.

Social choice theorists have identified alternative approaches to resolving elections in a single round that in theory avoid imposing a disadvantage on clustered candidates. These mechanisms require voters to rank either all candidates or some of their favorites in preference order. The mechanism that seems to receive the most attention these days is ranked-choice voting. This algorithm, sometimes referred to as instant runoff voting, eliminates candidates one by one based on who has the fewest first-place votes; when a voter's first-place candidate is eliminated, the second-place candidate assumes the top spot.

Ranked-choice voting, however, does not have a desirable property, known as the Condorcet criterion. An algorithm meets this criterion if it guarantees that it will always select a candidate who beats all other candidates in pair-wise comparisons, should such a candidate exist. For example, suppose 45% of voters have the preference ordering (1) Left (2) Center (3) Right, 40% have the preference ordering (1) Right (2) Center (3) Left, and 15% have Center as their first choice. Then, a majority of voters prefer Center to Left, and a majority prefer Center to Right, so a Condorcet method would choose Center. But ranked-choice voting would eliminate Center, ultimately selecting Left instead.

Defenders of ranked-choice voting suggest that this is highly unlikely in practice. For example, an analysis of 138 elections in the Bay Area using ranked-choice voting found that each election of the 138 had a Condorcet winner and that the ranked-choice mechanism in fact selected this winner. This may seem surprising, given the simplicity of the example above in which a Condorcet winner exists but ranked-choice voting does not select it. Another surprising result is that only 7 of the 138 elections chose a candidate trailing in the first round, indicating that ranked-choice voting rarely produces a result different from that of a system that simply chooses the candidate with the most first-place votes.

One possible explanation for these phenomena is that voters ranking their preferred candidates are not doing so in a vacuum, but instead are placing some weight on other voters' preferences. Political scientists have long noted the possibility of bandwagon effects, and it is plausible that a voter might want to vote for the election winner, or at least for a candidate who is the obvious alternative to the winner. Voters might do this even with a voting system in which they rank all their choices. A related possibility is that a voter does not want to "waste" a vote and seeks to act strategically, even though ranked-choice voting and Condorcet methods greatly limit (without eliminating) the possibility of strategic behavior. A voter who deep down prefers Elizabeth Warren, for example, might mistakenly believe that placing her near the top of the ballot will limit the voter's ability to make a choice between Bernie Sanders and Biden. We can think of this as a bandwagon effect too, though the motivation is quite different.

If voters change their heart-of-hearts rankings to favor candidates who are more popular among other voters, adoption of ranked-choice voting might make little difference. Consider, for example, a ranked-choice poll from about a week ago of Democratic primary voters. Given the rankings of voters, Sanders was the Condorcet winner and also would have won a ranked-choice vote, though with only a narrow head-to-head edge over Biden. This is in part because 27% of Sanders voters had Biden as a second choice and 38% of Biden voters had Sanders as a second choice. These results may seem surprising given the conventional wisdom that Sanders and Biden are in separate lanes, but makes perfect sense if there are some voters who will tend to place the candidates who have the best chance of winning at the top of their ranked-choice ballot.

To what extend do bandwagon effects undermine Condorcet methods? As a quick back-of-the-envelope approach, I ran a simple simulation many times (C# source code here). The gist is that I assumed that there are 10 candidates, each of whom has two attribute values randomly distributed from 0 to 1. Each voter also has a preferred value for each attribute and ranks candidates based on the sum of the absolute difference from the voter's preference to each candidate's attribute value. However, half of voters are susceptible to a bandwagon effect, in which they give some benefit to the two candidates who have the highest number of first-place votes overall. I then varied the size of this bandwagon effect.

This simulation allows us to distinguish latent Condorcet winners from apparent Condorcet winners. A latent Condorcet winner is a candidate who beats all other candidates in pair-wise comparisons when there are no bandwagon effects. An apparent Condorcet winner is a candidate who beats all other candidates in pair-wise comparisons when bandwagon effects exist. Arguably, we would like an election method to tend to choose latent Condorcet winners, even though voters' revealed rankings factor in bandwagon effects.

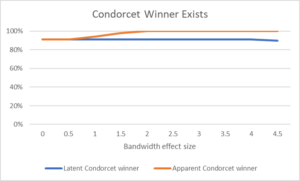

This simulation can help us answer whether bandwagon effects explain why apparent Condorcet winners seem to exist so often and why ranked-choice voting picks these so often. The figure immediately below shows how often the simulation produced latent and apparent Condorcet winners. With no bandwagon effects, Condorcet winners exist around 90% of the time; the other 10% of the time, some form of the Condorcet paradox emerges. But as bandwagon effects increase, the proportion of the time that a Condorcet winner emerges rises to 100%. Unfortunately, these are apparent Condorcet winners, reflecting how the voters vote but not necessarily the assumed latent preferences. This helps explain the result above that a Condorcet winner almost always appears to exist.

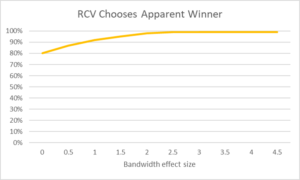

Similarly, the next figure demonstrates that the probability that ranked-choice voting chooses the apparent winner increases with bandwagon effects. Of cases in which an apparent Condorcet winner exists, ranked-choice voting succeeds at identifying that winner only 80% of the time in our simulations without bandwagon effects, but 100% of the time when the bandwagon effects are large. Again, this helps explain the result that ranked-choice voting seems to choose Condorcet winners, despite the absence of theoretical guarantees that it will do so.

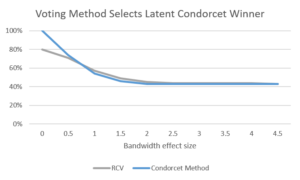

Changing from ranked-choice voting to a Condorcet method will not much improve the voting system's chance of selecting the latent Condorcet winner. The next chart illustrates the probability that a voting method selects the latent Condorcet winner. Condorcet methods are better than ranked-choice voting in the absence of bandwagon effects, but both are equally bad given bandwagon effects.

This suggests that when implementing some form of preference balloting in elections with many candidates, the most important challenge is to persuade voters that they should reveal their true preferences and shouldn't worry about wasting their votes. Perhaps this information might be easier to convey with ranked-choice voting than with more complex Condorcet methods, because the dynamics of ranked-choice voting are more intuitively understood. If so, ranked-choice voting might be preferable to Condorcet methods, despite the latter's stronger theoretical properties. On the other hand, the superficial very strong apparent performance of ranked-choice voting may reveal that it is not easy to convince voters to express their true preferences. If that's so, seemingly more primitive voting systems, such as our own Presidential primary system, could be preferable.

This analysis doesn't tell us much about whether some type of Condorcet method might make a difference in a general election with a very small number of candidates. It seems plausible that adopting such a method might allow for the emergence of a centrist third party in the United States. Ranked-choice voting would be unlikely to make a difference, since the centrist candidate would have the fewest votes. But it seems plausible that a centrist candidate might be able to convince many voters to place her second on the ballot, and a Condorcet method could then choose this candidate as the winner. Precisely for this reason, ranked-choice voting, which makes little difference, may be much more politically feasible than a Condorcet alternative.

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

The reason these candidates are dropping out is because Bernie Sanders and his supporters are almost as bad as Trump and his Deplorables. So Bernie tried to steal the nomination last time using superdelegates and this time he has changed his position and says superdelegates should have no role in the nomination. That wouldn’t be such a big deal but his supporters are so gullible and uncritical thinkers that they believe Trump and Putin when they say the DNC is trying to steal the nomination from him.

So Bernie has lost half of his support from 2016 and unfortunately the media said he won some of the early contests by getting weak pluralities. So just as Bill Clinton “won” NH by coming in 3rd the media should have been portraying Bernie as the early loser and maybe the other candidates could have stayed in longer to see how everything plays out...but with Bernie involved that is simply not an option.

It would be interesting to see if score/range voting would be helpful. I would suspect with strong enough strategic voting, it would not matter.

I still don't understand why ranked choice (I'll refer it to as IRV) is popular given its large drawbacks compared to approval or score voting and Arrow's theorem (which does not apply to range voting). The lack of Condorcet criterion is one bad property, but the lack of monotonicity (meaning a voter improving the ranking of a candidate can cause that candidate to lose, and decreasing the rank of a candidate can cause that candidate to win) is worse in my opinion. (I would also argue that the IRV "loser" being able to be the winner also seems problematic.)

An especially enlightening way of seeing different voting schemes (using simulations) is with "Yee diagrams" or "Yee pictures", http://zesty.ca/voting/sim/.

Very cool charts. Thank you for posting the link.

I want to dig into the math before accepting the author's critique of ranked choice/instant runoff but it's certainly an interesting approach to the question.

Whether or not the condorcet effect is a good thing, and wherever bandwagon effects fit, one more issue which is lost in ranked-choice voting is winnowing, over time, thru further information. As crazy as our presidential primary system and its schedule are, there is something to be said for an extended process which digs out more information about the personalities, qualifications, and nuanced positions of the candidates.

Ranked voting has an underlying assumption that there is a moment in time when most voters have enough information to make informed choices. But in a field of a dozen candidates, that's not really the case. Among three or four, maybe. Even if we sort of know how the candidates cluster -- or as the journalistic terminology describes it, which lanes they are running in -- that description of clusters or lanes is an oversimplification: Biden, Buttigieg, Klobuchar and Bloomberg are by no means just fighting for the same lane, for the same subgroup of voters. But simplified description is necessary when there is 'too much information'. In effect, too much is too little, therefore the need for more time to get more information.

In some parts of the country -- especially where for a long time there was one-party Democratic rule -- we are used to having run-off elections. If no candidate gets an absolute majority, then there us a run-off between the top two. Ranked voting aims at the same idea, with two major differences: First (and perhaps for the better), it prunes from the bottom rather than down from the top. Second (and perhaps not for the better), the 'instant runoff' as it is called, doesn't bring in new information.

I'm not sure it assumes there's a moment when most voters have enough information, as much as it assumes there's a moment when they have to go with the information they have. That there's only one election day.

If I had to identify the real problem with primaries, it's that they represent election campaigns between people who are, in some sense, "on the same side", and anticipate needing each other's supporters in the general election. This causes the candidates to go easy on each other, preventing critical information from being exposed.

Then they get to the general election, facing opponents who don't suffer the same handicap, and new information comes out that might have changed the outcome of the primary had it been exposed earlier.

(A) That's a strategic choice that folks can make, but I'm not sure there's any vote-system that would force candidates to go after their own party members as hard as they would go after members of the other party.

(B) That said, have you been watching the debates? "Going easy on each other" hasn't been a problem.

You are conflating ranked-choice voting with multi-state primaries. They are two entirely different questions.

Voters in New Hampshire have one chance to vote. They get no opportunity for new information to change their votes. Yet they are forced to "select" their candidate based on a plurality only. Ranked-choice would give them a different mechanism to select their candidate.

Voters in Iowa get the advantage of new information that the New Hampshirans didn't have. But Iowan's also get only their one chance to vote. Implementing ranked choice does not mean abandoning the state-based primaries spread over time.

Re-reading your comment, it seems like you are advocating a return to actual run-off elections within each state. That's just not going to happen. It's way too expensive and far too much a burden on voters. We can barely motivate people to get to the polls the first time. You want them to come two, three, four, potentially ten more times until we get an actual winner? And yes, those tenth-time voters will be more informed based on information released since the first vote - but we're not going to do the same thing for voters in states that reached a simple majority in their first vote? That makes no sense.

I do think the bandwagon effect (BE) is in play, and that it accounts for some of the results so far. But my hope is that, over time, as people get used to using ranked voting, people will be less influenced by BE. (But, since I suspect that BE is largely subconscious, it might be wishful thinking on my part.) The research I've seen so far indicates that using ranked voting almost never has a "bad" effect (ie, Yielding a result that seems counter-intuitive or "unfair.").

It seems fairly easy to come up with what seem like counter-intuitive results to me. Suppose you had three candidates, B(est), O(kay), and W(orse). A B>O>W vote means Best is 1, O is 2, and W is 3. Imagine that it is more important to you that B or O wins. Then we could imagine an election where the honest vote would be

30 W>O>B

10 O>B>W

10 O>W>B

25 B>O>W

So W wins [O is eliminated and we have 40 for W and 35 for B]. Suppose instead you and 5 other B>O>W voters decide to vote O>B>W (6 total votes change). Now we have

30 W>O>B

10 O>B>W

16 O>W>B

19 B>O>W

Now O wins [B is eliminated, 30 for W and 45 for O]. In fact suppose you and the 5 other people simply did not vote, then O gets 39 and W gets 30, so not voting was better for your preferences than honestly expressing your vote.

Apologies. On the second set, I mixed up the numbers when putting them into the form.

It should be when B>O>W switch to O>B>W that we have

30 W>O>B

16 O>B>W

10 O>W>B

19 B>O>W

Sorry, again about that. You can also look up the 2009 Burlington mayoral election for a case of IRV not working well.

Why are we attempting to fix something that ain't broke? We have 240+ years of voting experience. The jury came back: Counting actual votes cast by legal voters works.

Actually, even by your standard, our history of ensuring the franchise is...not great.

Nice move of the goalpost, Sarcastr0. I said nothing wrt franchise. 🙂

"ain’t broke" and "disenfranchises" shouldn't be compatible.

Indeed. I thought that was obvious.

Our 240+ years of experience seems to say that plurality-based voting (that is, simply counting votes where the voter is allowed to express one and only one choice) tends to lead to polarization and wide political swings by favoring candidates at the extremes over moderate candidates. It prioritizes loudmouths who can "motivate their base" over sober candidates with judgement and discretion.

That does not sound to me like "something that ain't broke".

Upon reviewing the math, I've become pretty convinced that the goal of better capturing the intent of the voting public is a pipe dream. We just need to tune to how much elitism vs. populism we want in our vote, and what sorts of elites we wish to foreground.

Of course, that'll never happen nationally because you will always have one party advocating for the status quo.

Locally, I wouldn't mind some innovative folks trying some stuff.

Setting aside single-position elections (that is, there can be only one President, each state only has one governor, etc. and so-on), the "Best" option to capture the "intent" of the voter is proportional voting multi-seat districts.

That's also the option that allows third-parties a fair shake. Makes gerrymandering damn-near impossible to boot.

I've written a couple of White Papers on IRV (so-called Ranked Choice) for the Indiana Senate Committee on Elections, after a local state senator proposed IRV. Main argument was that IRV's discard algorithm is illegal (both unconstitutional and a violation of state "voter intent" laws) . Not counting all the votes in not acceptable. To date, this has never been adjudicated - it was never advanced by the plaintiff in Maine, for example.

As to the main point, I'm skeptical about a "bandwagon effect". However, it makes complete sense that voters in a primary in which they have lots of information about the likelihood given choices will prevail against the incumbent will "hedge" if given the change. I daresay we saw some of that last night with the massive vote for Biden. I'd expect that with Condorcet, balancing one's preferences with one's hatred of the incumbent and the need to defeat him will affect strategy.

One of my proposals for Indiana was to conduct an extensive study of multicandidate primary and general elections (Libertarians have ballot access here). In Primaries, would ask for straight ranking preference. Did you base your ranking on who could best beat the incumbent? If yes, ask for ranking if this was for the seat.

IRV hasn't been good for third parties in Australia. Condorcet, as you have pointed out, might well be. I've made a similar argument to yours: Condorcet could work over time against extremists and facilitate choosing among some collection of rational centrists.

I can't speak to IL state law claims but I am skeptical of your argument that IRV is unconstitutional. To be blunt, your claim that it amounts to "not counting all the votes" is just wrong. Every vote is counted - in pass one. Based on the results of pass one, a candidate is eliminated - and every vote is again counted in pass two. You could accomplish exactly the same result by eliminating the lowest candidate and holding the run-off election the next day. No one has ever claimed that the in-person run-off amounts to not counting votes. Asking voters to make that second decision as a hypothetical on the original day is mathematically identical. It may or may not be good policy but there are no constitutional problems with it.

Excuse my typo. Should have been Indiana state law.

Addendum: I must take issue with the idea that Condorcet is more complicated than IRV. The ranked ballots are identical. Unless they are told, they have no idea what algorithm is being used. A mechanic/engineer may know the differences in a number of different 4-cylinder engines but most drivers aren't going to care all that much about what's going on "under the hood".

There are some ways that the way ballots are treated would likely differ between IRV and Condorcet. In Australia and where it has been used in the US, ALL rankings must be filled. This is probably due to preference truncation. With Condocet people could rank candidates or even just "bullet vote" - pick only one. My personal preference is Condorcet-with Approval. Thus, in 2016 in the GOP Primary, I would have ranked Rand Paul #1 and ranked Cruz and Rubio both #2. Mathematically there is no difference with Ranking Paul #2 and Cruz and Rubio #4. This helps with "intent of the voter".

The only time I would care about a ranked-choice ballot is when you have candidates dropping out after early voting has already begun. It would be nice to at least have an option to say "I vote for Candidate A, but if she drops out before election day, I vote for Candidate B." So the second choice would never be counted unless the first choice had dropped out.

I stand by my position that the Hunger Games provides the best model for picking a winner.