The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Bail Reform in Chicago Appears to Have Increased Crime

A reanalysis of data from the Cook County courts suggests that as more defendants were released before trial, more crimes resulted

In a study posted on SSRN today, my colleague Professor Richard Fowles and I explore the public safety implications of recent Cook County bail reforms. We review the Cook County Chief Judge's study of these reforms, which sanguinely asserted that as more defendants were released pretrial no additional crimes resulted. We believe that, properly assessed, the study's own data suggests a significant increase in crimes as a result of the changes. Our conclusions may have broader implications about the public safety dangers of bail reform.

Bail reform issues have recently been in the news across the country. Reformers and their critics have argued about the need to make the nation's pretrial release procedures fairer while at the same time protecting the public from crimes by defendants released while awaiting trial. Reformers have argued that traditional cash bail requirements for pretrial release needlessly incarcerate many indigent individuals merely because they are unable to raise the required sums. In light of that widely accepted criticism, many jurisdictions have experimented with new procedures that reduce the use of cash bail as a requirement for a defendant's release and, more broadly, that release more defendants before trial.

Bail reform critics have responded that the expanded release of defendants produces additional crimes. For example, in New York, more generous pretrial release procedures have been blamed for an upsurge in crime at the beginning of this year. As bail reform measures continue to spread across the country, debates about effects on public safety will likely be at the forefront as such reforms are considered.

We tend to agree with critics of cash bail, who argue it is not the best means for regulating pretrial release. But the broader question of how many defendants can safely be released pretrial is the critical one. One opportunity to empirically assess these public safety issues has recently developed in one of the nation's largest trial court systems: The Circuit Court of Cook County, Illinois (which includes Chicago). On September 18, 2017, the Chief Judge of the Cook County Circuit Court (Judge Timothy Evans) implemented sweeping bail reforms by issuing an order, which was designed to reduce reliance on money bail and, more important, increase pretrial releases in Cook County courts. A year-and-a-half later, Chief Judge Evans reviewed the results of these new procedures and published a study entitled "Bail Reform in Cook County." The Bail Reform Study trumpets the fact that the new bail reforms led to a significant increase in the percentage of defendants who were released pretrial—from about 72% of all defendants to about 81% of all defendants. And the Study also argues that this increase in pretrial releases was accompanied by "considerable stability" in the "community safety rate" of the releases. Specifically, the Study claims that the new, more generous release procedures did not increase crime, stating that "[i]t should be noted that the increase in pretrial release has not led to an increase in crime" and that "bail reform has not led to an increase in violent crime in Chicago."

Such research designed to develop empirical evidence on the effect of new judicial practices is commendable. And yet, it is obviously important that any "reform" measure be a genuine improvement. Only if an empirical study reports what has happened after a change in judicial procedures can the desirability of the reform measure be fully assessed.

Professor Fowles and I have teamed up in the past, including conducting empirical research on the 2016 Chicago homicide spike (which we believe can be attributed to an "ACLU effect") and on Miranda's harmful effects on crime clearance rates. Having closely reviewed the Study, we disagree with its upbeat conclusions regarding public safety after changes to pretrial release procedures.

The Study fails to recognize that, given that more defendants were released after the reforms, even a "stable" rate of "community safety" will inexorably lead to more crimes. That stable rate of safety—and, inversely, the stable rate of failure or public safety danger—would be applied across a larger pool of released defendants, which necessarily means that the public will suffer more crimes. In other words, at least in Cook County, more bail reform apparently means more crimes committed against the public.

In addition, we find that, contrary to the Study's suggestion of stable numbers of crimes, there appear to have been significant increases in crimes committed by pretrial releasees. The Bail Reform Study artificially allowed the pre-reform defendants more time to commit additional crimes than the post-reform defendants, observing the "before" defendants for (on average) 243 days and the "after" defendants for (on average) only 154 days. As a result, the Study's construction skewed the results towards finding a lower recidivism rate after the change.

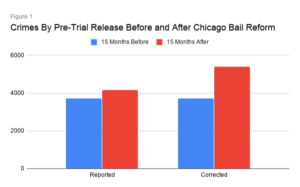

It is not an apples-to-apples comparison to look at one group of defendants who were released and observed for, on average, 243 days and then to compare them to another group of defendants who were released and observed for, on average, 154 days. We use Cook County data to estimate what would have happened if the Study had observed both groups of defendants for the same amount of time. Properly estimated, the number of defendants who were charged with committing new crimes after bail reform increased by about 45%, as shown in Figure 1 below (comparing crimes by pretrial releasees before and after bail reform--with the first two columns being what was reported by the Study and the second two columns being what we estimate actually happened assuming comparable observation periods).

And, more concerning, using the same methodology, the number of pretrial releasees who committed violent crimes increased by about 33%.

In addition, as reported last week in a hard-hitting investigative report by the Chicago Tribune, good reason exists for thinking that these figures on violent crimes committed by releasees may have undercounted what actually happened after the reforms, including undercounting a significant number of homicides by pretrial releasees. And finally, as also reported by the Chicago Tribune, the number of aggravated domestic violence prosecutions that prosecutors dropped increased from 56% before bail reform to 70% after. A reasonable inference is that the increase was likely the result of batterers being able to more frequently obtain release and intimidate their victims into not pursuing charges.

Using all this information, we believe it is reasonable to estimate that Cook County's expanded pretrial release procedures led to about 930 additional crimes against persons in the fifteen month "after" period compared to the "before" period. (For these purposes, we define "crimes against persons" as including the FBI's Uniform Crime Reports "violent" crimes of murder, attempted murder or non-negligent manslaughter, rape, robbery, and aggravated battery, and add domestic battery, battery, assault, assault with a deadly weapon, and armed violence.)

These public safety harms call into question whether the bail reform measures as implemented in Cook County were clearly cost-beneficial. And because Cook County's procedures are state-of-the-art and track those being implemented in many parts of the country, Cook County's experience suggests that other jurisdictions may similarly be suffering increases in crime due to bail reform. Accordingly, our findings may be useful to policymakers elsewhere as they consider whether and how to implement changes in pretrial release procedures.

You can download our new study here.

Show Comments (111)