The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

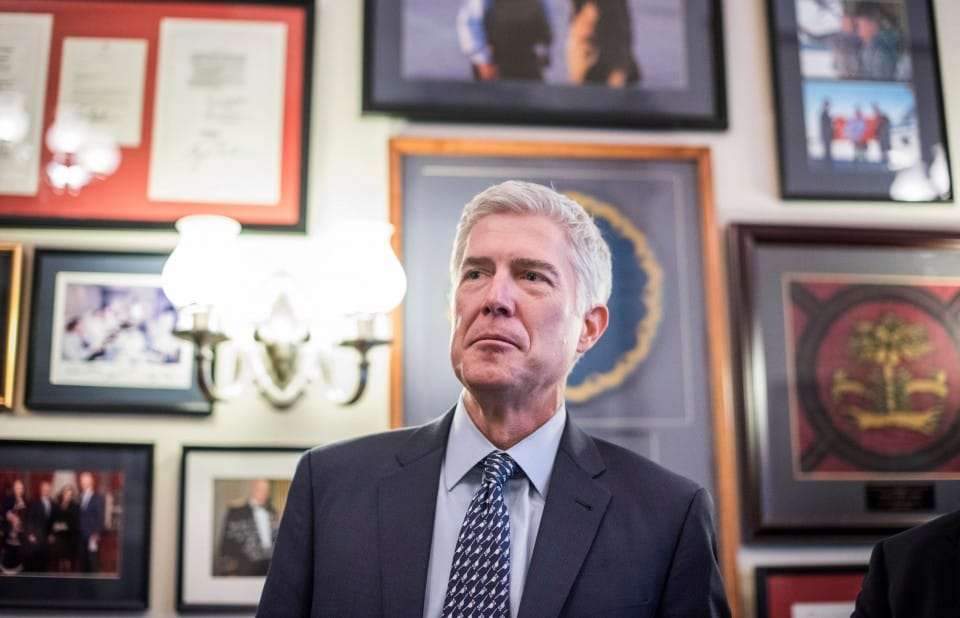

On Gorsuch, Garland and inconsistency

On the merits of Judge Neil Gorsuch's nomination to the Supreme Court, let me just add my voice to the choir: It's both a very good pick and a very smart pick. Very good because Gorsuch has the qualities we want in Supreme Court justices: He's thoughtful, smart and judicious, with a deep appreciation for the constitutional role of the judiciary within a system of separated powers, and a track record of real distinction on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 10th Circuit. He has the potential to be an outstanding justice. He's a very difficult nominee to oppose on any grounds relating to his qualifications to sit on the Supreme Court.

And that makes it a smart pick. The Democrats, and a fair number of our fellow citizens, were gearing up for a big fight on this one. My guess is that much of the fight has now been knocked out of them, and the big fight will not materialize - which is probably just as well. Given the state of things at the moment, a little cooling off might not be such a bad thing.

(Plus, now that the door has been opened for SCOTUS clerks from the 1993-1994 term, surely Eugene's appointment will follow when the next vacancy arises!)

So President Trump gets high marks on this one.

That's not to say that the Democrats don't have good cause to try to block the appointment; I think they do. This seat should have been filled by Merrick Garland - another nominee whose credentials were absolutely impeccable. I was one of those who thought (and still think) that the Republicans' failure even to consider his nomination was outrageous.

Nor do I think that this argument can be as easily dismissed, as co-blogger Jonathan Adler does [see: "No, obstruction of Neil Gorsuch is not about Merrick Garland"]. "The problem with this argument," Adler wrote, is that:

Most Senate Democrats were willing to filibuster a Supreme Court nominee before Garland was nominated, let alone blocked by Republicans. Indeed, before Barack Obama was even elected president, prominent Senate Democrats and progressive activists tried (but failed) to filibuster President George W. Bush's nomination of Samuel Alito. Thus, the argument that the only reason Senate Democrats would filibuster Gorsuch is payback for Garland is complete and utter nonsense.

I disagree. Whether a filibuster is appropriate in this circumstance can (and should) be debated on the merits, and I really don't see how the positions people may or may not have taken in the past on similar questions, and whether or not those prior positions are consistent with current positions, are germane to that question. (And this principle certainly cuts both ways; any inconsistencies in the views of those who might be supporting, say, the construction of a "border wall" with Mexico aren't germane to the question of whether that is or is not good for the country.)

The Democrats have ample justification for a filibuster, in my opinion; but I agree with University of California at Berkeley professor Dan Farber (whose blog post on the nomination was flagged earlier by Eugene) that those in the loyal opposition might want to keep their powder dry on this one:

Why not filibuster and try to block the nomination? [1] The Republicans were wrong in what they did to Garland, and the Democrats were right that this kind of behavior is damaging to the Supreme Court as an institution. [2] Blocking a nominee for a year when you have a majority of the Senate is one thing; blocking any appointment for four years when you're in the minority is much less feasible (and more damaging to the court). [and 3] The key thing about Gorsuch from my point of view is that he's principled - and he seems to have enough backbone to stand up to Trump. We could use that on the court. The fact that Gorsuch has spoken against judicial deference to the executive branch in matters of statutory interpretation makes it more likely that he won't rubber-stamp Trump's actions.

Hide Comments (0)

Editor's Note: We invite comments and request that they be civil and on-topic. We do not moderate or assume any responsibility for comments, which are owned by the readers who post them. Comments do not represent the views of Reason.com or Reason Foundation. We reserve the right to delete any comment for any reason at any time. Comments may only be edited within 5 minutes of posting. Report abuses.

Please to post comments

Mute this user?

Ban this user?

Un-ban this user?

Nuke this user?

Un-nuke this user?

Flag this comment?

Un-flag this comment?