The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

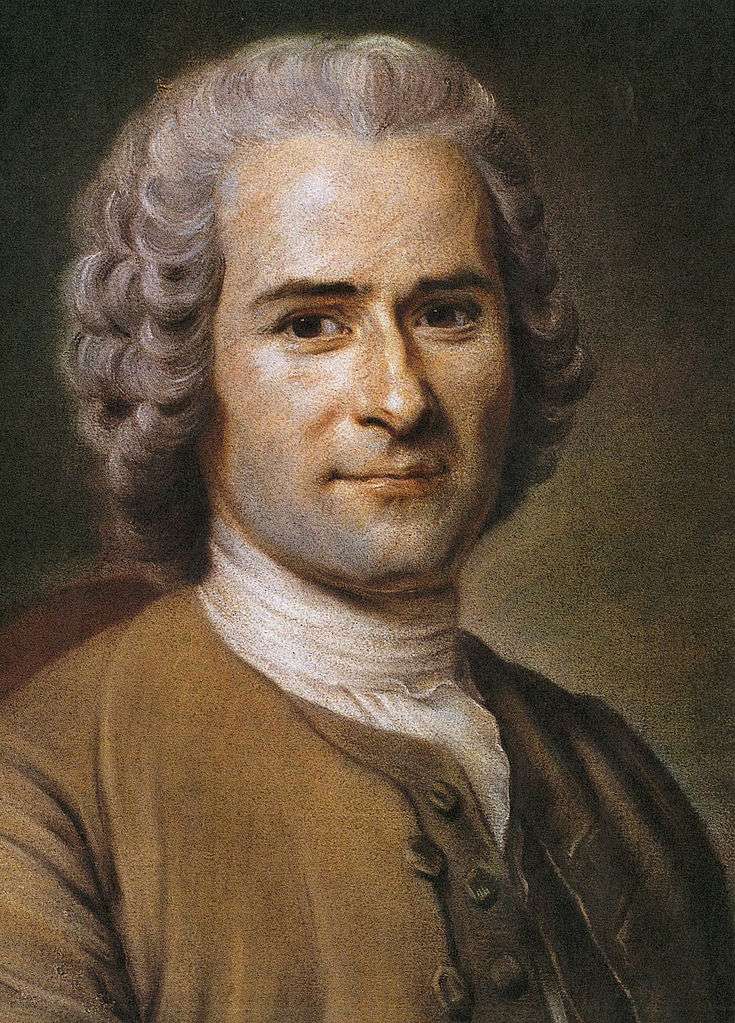

Jean-Jacques Rousseau: Not a nut, not a leftist, and not an irresponsible intellectual

Thanks very much to Eugene for inviting me to blog about my recently published book, "Rousseau's Rejuvenation of Political Philosophy: A New Introduction (Palgrave Macmillan, 2016)."

No modern philosopher has been more influential than Rousseau, or more misunderstood. There is scarcely a modern intellectual or political movement whose seeds cannot be seen, rightly or wrongly, in some aspect of Rousseau's thought - the French Revolution, communism, fascism, contemporary communitarianism, as well as the politics of compassion and political leaders who take on the role of public comforters.

We can add Romanticism and its vision of the sensitive artist as a moral preceptor, along with Montessori schools and related forms of child-centered education. The hippies of the 1960s and the quasi-religious environmentalists of today. The animal rights movement. Depth psychology and our contemporary culture of public confessions. So many disparate echoes reflect the puzzling richness and complexity of Rousseau's writings.

Rousseau was the first great philosophic critic of what we call the Enlightenment, without being a defender of the ancien régime. Right from the start, he was seen by his critics as a mad father of mad fantasies. The leading philosophers of the French Enlightenment treated their former friend and colleague as a deranged traitor. He was seriously persecuted by governments and clergymen in both Catholic and Protestant parts of Europe, and celebrated after his death by those who made the French Revolution.

Political conservatives, whether of a classical liberal or traditionalist orientation, have generally found Rousseau repulsive and dangerous, and his admirers tend to be on the political left. One striking exception to this generalization is Alexis de Tocqueville, who said that Rousseau was a man (along with Montesquieu and Pascal) with whom he spent time every day.

Tocqueville is among the most reputable analysts of American life, among people of a wide range of political views. His respect for Rousseau should caution us not to buy the caricatures peddled by people who read carelessly and write recklessly.

My book seeks to reintroduce Rousseau to an American audience, at a time when America is not the exuberant young experiment in democracy that Tocqueville observed. Unlike Tocqueville, Rousseau took his greatest philosophic inspiration from Plato, who wrote during a period of democratic decadence in Athens.

Rousseau's principal goals as a writer were the same as Plato's: to provoke potential philosophers to engage in philosophy, and to be useful to those who cannot pursue the philosophic life. Both writers are primarily diagnosticians of political pathologies rather than than would-be political reformers.

Even more fundamentally, they were philosophers who sought to learn solely in order to know. For all of their apparent differences, both of them treat political philosophy as a means of protecting political life and the life of philosophy from threats that each poses to the other. The skill with which Rousseau invites his readers to think for themselves makes him a useful introduction both to Plato and to philosophy.

The book has three main parts. The first two substantive chapters deal with Rousseau's account of the evolution of humanity, which is central to his thinking about politics. Since his time, scientists have made fascinating new discoveries - about primitive peoples, physical evolution and the behavior of our fellow primates - that support the principal elements of his account.

This is important for at least two reasons. First, if Rousseau were refuted by newly discovered evidence, it would raise serious questions about the validity of the implications that he drew from his scientific inquiries, including the political analysis that rests on those implications. Second, his treatment of human origins illustrates his approach to science or natural philosophy itself, an endeavor to which he gave considerable attention. His prescience suggests that he had a deeper understanding of the possibilities and limitations of modern science than many of us have today.

The next two chapters consider some of Rousseau's efforts to bring his philosophic insight to bear on problems presented in the modern world. These include the place of women in society, the viability of traditional family structures, and the role of religion and religious freedom in nations that are becoming ever more secular. In considering these issues, the book gives special attention to examples that illustrate how Rousseau used what he found in Plato. Seeing how he used Plato can help us see how we, in turn, might use Rousseau.

A last chapter complements the treatment of natural science at the beginning of the book. The American Constitution is the most successful application of the Enlightenment's new political science, and Rousseau was deeply skeptical about the promises made by proponents of that science. Nevertheless, when read in the manner suggested by the previous chapters of this book, his political writings offer considerable support for important features of America's constitutional arrangements.

At the same time, Rousseau's analysis points to the merits of certain dissident or subdominant strains in American political thought. A proper understanding of these two features of Rousseau's analysis suggests that American students of politics should reconsider the widely held view that Rousseau is a useless or dangerous guide for us. Even more important, perhaps, Rousseau (like Plato) illuminates the obstacles facing those who aspire to replace political philosophy with political science.

The remainder of the posts this week will summarize a few of the reasons for Americans, and especially the conservatives who have been his harshest critics, to take Rousseau seriously.

[Nelson Lund has been guest-blogging this week; parts of these posts are borrowed from his book.]

Show Comments (0)