The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Who owns ‘We Shall Overcome'?

Hot on the heels of the news that Led Zeppelin's "Stairway to Heaven" is the target of a copyright infringement suit comes word that an even more iconic musical work - the song "We Shall Overcome," a song the Library of Congress called, with considerable justification, "the most powerful song of the 20th Century" - is also embroiled in a copyright dispute. The "We Shall Overcome Foundation" has filed a class-action suit in federal court (SDNY) against the two music-publishing companies, Ludlow Music and the Richmond Organization, that (according to the complaint) have been asserting ownership of the copyright to "We Shall Overcome." The plaintiff seeks a judgment from the court declaring that the defendants' copyright claim is invalid and ordering the defendants to disgorge previously collected licensing fees.

The complaint makes for pretty interesting reading, at least to those interested in this particular slice of musical and cultural history. (Incidentally, but surely not just coincidentally, the plaintiff is being represented by the same law firm, Wolf Haldenstein, that was behind the recent successful challenge to Warner/Chappell Music's absurd claims that it owned the copyright to "Happy Birthday to You.")

There are two kinds of copyright cases: those that are only about the money, and those that are really about (or, at least, also about) something a little deeper, something about the work of art itself or the place it holds in our culture. The vast majority are, like the Led Zeppelin case, in the first category. (One tip-off that usually indicates that it's only about the money: Lots of copyright litigation begins with a claim not by the author of the work in question, who usually does care about the work, but by his or her heirs, or institutional assignees of the original copyright, who really don't care much about the work but care a lot about the stream of licensing revenues it produces - and continues to produce year after year after year, long after the author or artist's death.)

Not that there's anything wrong with going after the money if you think you have legal entitlement to it, but it's the cases in the other category that tend to be more interesting. And this is one of those.

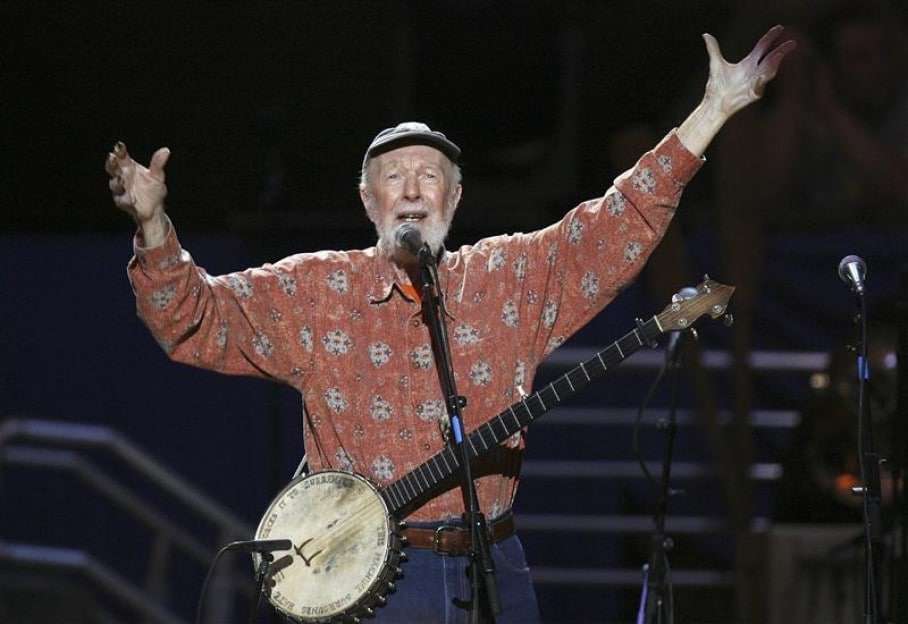

I don't know about you, but I was a little astonished to learn that anyone actually claimed to own the copyright of "We Shall Overcome." But - again, taking, as they say in the law, the factual allegations in the complaint as true - the defendants apparently do. I thought it was just a "folk song," written by a whole bunch of people over time; I had heard vague reports that Pete Seeger claimed to have written the song, based on an earlier spiritual, but I had assumed that Seeger, of all people - one of America's last true communists, for goodness' sake - wasn't suing people for infringement when they sang the song or collecting any royalties from performances or recordings of the song.

The defendants, though, trace their ownership claim to a 1963 copyright registration for a "derivative work" titled "We Shall Overcome," filed on behalf of Seeger and three others (Zilphia Horton, Frank Hamilton and Guy Carawan). Without presuming to evaluate the strength or weakness of that copyright claim, I must say it looks dubious to me. The complaint has unearthed dozens of different versions of the song floating around in the 1940s and '50s:

The musical composition We Shall Overcome is an adaptation of an earlier public work, an African-American spiritual with exactly the same melody and nearly identical lyrics ("We Will Overcome"). . . . The first known printed reference to "We Will Overcome," is the February 1909 edition of the United Mine Workers Journal, [which] refers to performances of that song in 1908 and much earlier. The front page of the February 1909 United Mine Workers Journal states: "Last year at a strike [in Alabama], we opened every meeting with a prayer, and singing that good old song, 'We Will Overcome." . . . In the 1 940s, We Shall Overcome was used as a protest song by striking tobacco workers in Charleston, South Carolina.

And even Seeger and Horton, two of the supposed authors of the song, had published an earlier version of the song way back in 1948, with an accompanying note:

This simple and moving hymn tune becomes especially thrilling when you consider where the song was first sung. It was learned by Zilphia Horton of the Higlander Folk School, in Tennessee, from members of the ClO Food and Tobacco Workers Union. Many a visitor to the south has never forgotten hearing the rich harmonies of some little band, and the determination in these words, even though surrounded on all sides by hate, Jim Crow and all the forces of power and money. Zilphia writes: "It was first sung in Charleston, S.C., and one of the stanzas of the original hymn was "we will overcome." At school here they naturally added other verses. . . . Its strong emotional appeal and simple dignity never fails to hit people. It sort of stops them cold silent."

When the purported "authors" of the song so freely admit that it was first sung by others, and that "other verses" were being added by lots of people, that starts to look like a pretty slim reed on which to base a copyright claim.

But putting aside whether they have a valid copyright, what they're doing with that copyright is the more interesting part here. The plaintiff, Isaias Gamboa, formed the WSO Foundation in order to make a documentary film about the song (following up an earlier book on the subject). Upon learning that there was an outstanding copyright claim to the song, he wrote to Ludlow and Richmond to request a quote a "synch license" - a standard license allowing the use of a copyrighted musical work in a motion picture in exchange for a royalty.

He received the following reply:

WE SHALL OVERCOME is a difficult song to clear. We will need to review the recording that is intended to be used. The song cannot be cleared without reviewing what's being sung and the quality of the representation of the song. Please provide this information so that we can further process.

After Gamboa sent in the recording he wanted to use in the film, Ludlow/Richmond replied:

We apologize for the delayed response to you. As previously mentioned WE SHALL OVERCOME is a very difficult song to clear. The song is not available for the proposed use.

More back-and-forth ensued, with the defendants eventually writing:

As previously mentioned, permission is not granted for this use. I will continue to follow up with our historians. However, until further notice we do not grant permission for the use of WE SHALL OVERCOME in the documentary. No other information is available. TRO-Ludlow Music, Inc. reserves all rights under the United States Copyright law in connection with this usage.

So this case is not about the money in the sense that the defendants aren't asking for any money - they're prohibiting the plaintiff from using the work at all.

Ludlow Music, also not just coincidentally, tried several years ago to do the same sort of thing with another questionable copyright it claims to own - Woody Guthrie's "This Land Is Your Land." Woody Guthrie! The same Woody Guthrie (Seeger's communist pal) who once wrote the following note to accompany the sheet music to one of his songs:

"This song is Copyrighted in U.S., under Seal of Copyright # 154085, for a period of 28 years, and anybody caught singin it without our permission, will be mighty good friends of ourn, cause we don't give a dern. Publish it. Write it. Sing it. Swing to it. Yodel it. We wrote it, that's all we wanted to do."

Why would Ludlow Music not permit someone to use "We Shall Overcome" in a documentary film? It smacks - and I emphasize again that I've only heard one side of the story, my efforts to get Ludlow to give me its side of the story having been thus far unavailing - of a kind of "copyright censorship" that is one of the least attractive features of our current copyright practice. (See my earlier posting on this here.) "We Shall Overcome" surely forms part - a rather big part - of our shared cultural heritage; it is difficult to imagine trying to tell the story of the civil rights movement without it, and attempts to use a copyright claim - especially one that looks so flimsy - as a way to inhibit discussion and dissemination of the song strikes me as misguided and contrary to the public interest that copyright is supposed to serve.

Show Comments (0)