The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Is it 'content-based' for a speech restriction to distinguish 'political' signs, 'ideological' signs and event announcement signs?

This is the question the Supreme Court is facing Monday in Reed v. Town of Gilbert. (Disclosure: My UCLA First Amendment Amicus Brief Clinic students and I filed an amicus brief on behalf of Profs. Ashutosh Bhagwat, Eric Freedman, Richard Garnett, Seth Kreimer, Nadine Strossen, William Van Alstyne and James Weinstein, arguing that the court should hear the case.) I think the answer is that the law is pretty clearly content-based.

But an article by Garrett Epps in the Atlantic takes what strikes me as an odd view on the subject, and in particular on the history of what "content-based" meant:

The church [which is challenging the sign restriction] should, and almost certainly will, win. The distinctions between different temporary signs are arbitrary, and the times and sizes for "qualifying events" are almost punitive. What's important, though, is how it wins. The church argues that the sign code is "content-based." That, they say, is "because enforcement officials must examine what a temporary sign says before they can determine which provision of the code to apply." The Ninth Circuit called the sign code "content-neutral," even though officials have to read the signs. That's correct-properly read, the term "content-based" means based either on the viewpoint or the subject matter of the speech at issue.

Courts that use the term "content-based" invariably cite to a 1972 case called Police Department v. Mosley, which struck down a Chicago ordinance that banned picketing of schools but made an exception for "peaceful picketing of any school involved in a labor dispute." Justice Thurgood Marshall wrote for six justices that "above all else, the First Amendment means that government has no power to restrict expression because of its message, its ideas, its subject matter, or its content." That kind of restriction, the Court has held, triggers a rule of "strict scrutiny" of any viewpoint ("no anti-government speech") or subject-matter ("no religious speech") regulations. It's almost impossible for any law to survive "strict scrutiny," and laws based-like Gilbert's-on the need for aesthetic control of roadside signs are unlikely ever to do so.

Since Mosley, the phrase "content-based restriction" has become a shorthand phrase used by lawyers and courts. Until recently, it has meant a restriction or regulation of speech based on the "viewpoint" or the "subject matter" of the speech. The Gilbert code could be viewed as "subject matter" based - but it really isn't. "Meetings" is no more a subject matter than "marketing." The proper way to decide this is that the ordinance is too restrictive, and discriminatory among speakers.

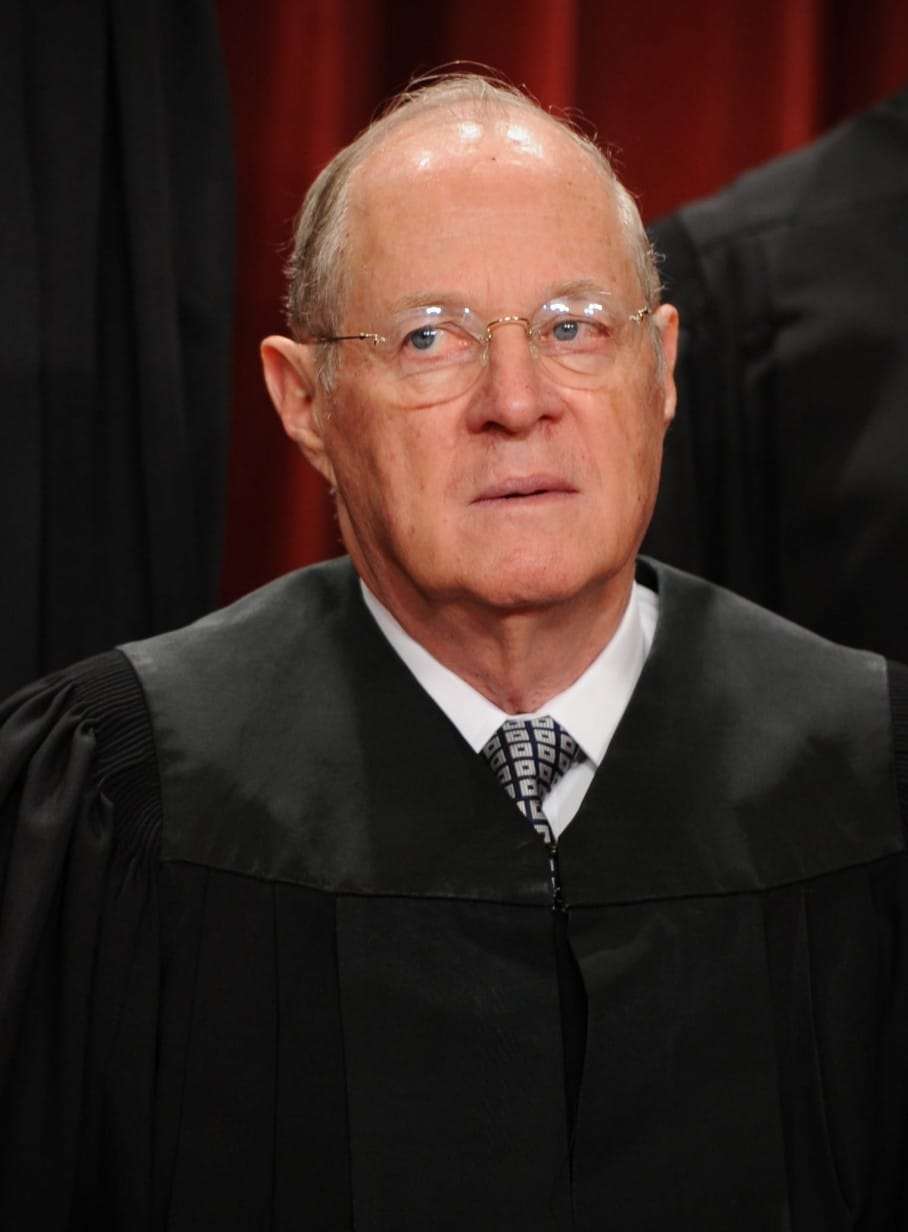

The slow degradation of "viewpoint-subject matter" rule is disconcerting. Justice Anthony Kennedy, in particular, has led the way in this area. In the unfortunate 2011 case of Sorrell v. IMS Health, Inc., he wrote (for six justices) that Vermont could not allow doctors to keep secret details about what drugs they prescribe from pharmaceutical companies seeking to sell them drugs. "The statute … disfavors marketing, that is, speech with a particular content," he wrote. The word "content" here has come unmoored. "Marketing" is not a "subject." It's an economic activity, to be regulated as needed by the specific market it involves. Kennedy's foggy version of "content" will - very soon - take us to a place where government can't regulate advertising at all. Already lower courts have applied the precedent to hold that cigarette companies have a First Amendment right to veto health-warning labels, and drug-company sales reps can encourage doctors to prescribe powerful drugs for unapproved uses.

Say what you like about what the law ought to be, but the court's broad understanding of "content-based" was hardly led by Justice Kennedy. From Mosley (1972) on, the court has repeatedly (not always, but repeatedly and usually) read "content-based" to mean "based on the words or images that speech contains." It has not limited this to "restriction or regulation of speech based on the 'viewpoint' or the 'subject matter' of the speech."

1. Let's begin with Mosley itself. Here's the Justice Marshall passage that the Atlantic piece quotes, with the sentence before and the citation immediately following:

The operative distinction [in the ordinance involved in this case] is the message on a picket sign. But, above all else, the First Amendment means that government has no power to restrict expression because of its message, its ideas, its subject matter, or its content. Cohen v. California, 403 U. S. 15, 24 (1971); [other citations].

But Cohen v. California held that a state may not ban vulgarity (there, "Fuck," in "Fuck the Draft"). The prohibition on vulgarity was not viewpoint-based (the state argued that it was the vulgarity itself, and not the viewpoint expressed about the draft, that made Cohen's speech punishable), and "fuck" is hardly "subject matter." Yet Mosley itself, 15 years before Justice Kennedy joined the court, treated "content-based" as covering such a restriction - unsurprising, given that Justice Marshall was condemning not just discrimination based on "ideas" and "subject matter" but also "message" and "content" more generally.

2. How about Erznoznik v. City of Jacksonville (1975)? The court struck down a ban on the display of nudity on drive-in movie theater screens that are visible from the street, citing Mosley and expressly labeling the law content-based. The court didn't, though, conclude that nudity was a viewpoint, or a subject matter. It just treated a distinction between movies that show nudity and movies that don't as content-based.

3. Or how about Regan v. Time, Inc. (1984)? There the court struck down in part a ban on distributing images of U.S. currency, because of its exception for "philatelic, numismatic, educational, historical, or newsworthy purposes." The exception, the court held, was content-based because "[a] determination concerning the newsworthiness or educational value of a photograph cannot help but be based on the content of the photograph and the message it delivers," so that "[t]he permissibility of the photograph is therefore often 'dependent solely on the nature of the message being conveyed.'" "Regulations which permit the Government to discriminate on the basis of the content of the message cannot be tolerated under the First Amendment." Now maybe you could argue that an exception for "newsworthy" or "educational" purposes is "subject matter" discrimination (i.e., subject matter doesn't just mean "speech having to do with abortion" or "speech having to do with the war," but includes such very broad categories) - but, if so, then the discrimination among political signs, ideological signs, and event-announcing signs would be at least as subject-matter-based. And of course in none of these cases was Justice Kennedy even on the court.

There's also Florida Star v. B.J.F. (1989), which struck down a law imposing liability on the publication of the names of rape victims; Cohen v. Cowles Media Co. (1991), stressed that the holding in Florida Star was based on the fact that "the State itself defined the content of publications that would trigger liability." Again, it's hard to see the law as discriminating based on viewpoint or even subject matter (it had to do with a particular fact, not a general subject of discussion); and if one does see such a classification as being "subject-matter-based," surely the same would be true with distinctions based on whether a sign is political, ideological, or event-related. Instead, it seems most logical to view the Court as having long recognized that content discrimination generally includes discrimination based on what speech is saying, beyond just the viewpoint or the subject matter. And though Justice Kennedy participated in those two cases, he didn't write them, and was just one of the majority Justices. (Justice Kennedy did play a prominent role in one debate about what counts as "content-based," in Hill v. Colorado (2000); but Justice Kennedy's opinion wasn't discussed by the Atlantic article, and it didn't involve a retreat from any preexisting understanding of content discrimination.)

So (1) there is no "slow degradation of 'viewpoint-subject matter' rule" - the term "content-based" was often understood by the court as broader than just "viewpoint-or-subject-matter-based," starting with Mosley itself - and (2) Justice Kennedy didn't lead the way in this area. But beyond this, (3) there was nothing at all novel or leading about Justice Kennedy's point in Sorrell that discrimination between "marketing" (i.e., commercial advertising) and other speech is content-based. City of Cincinnati v. Discovery Network, Inc. (1993) held, in an opinion by Justice Stevens (with Justice Kennedy as just one of the signatories), that a ban on newsracks that had "commercial" (in the sense of purely advertising) newspapers was content-based. Though the city argued that "the justification for the regulation is content neutral," Justice Stevens wrote that, "The argument is unpersuasive because the very basis for the regulation is the difference in content between ordinary newspapers and commercial speech."

And even earlier, in Metromedia, Inc. v. City of San Diego (1981) - again, before Justice Kennedy joined the Court, and less than a decade after Mosley - a majority of the justices treated a distinction between commercial and noncommercial advertisements (albeit there one that favored commercial advertising) as content-based. Responding to the dissent, Justice White's plurality opinion (joined by Justice Marshall) said,

By "essentially neutral," the Chief Justice may mean either or both of two things. He may mean that government restrictions on protected speech are permissible so long as the government does not favor one side over another on a subject of public controversy. This concept of neutrality was specifically rejected by the Court last Term in Consolidated Edison Co. v. Public Service Comm'n…. On the other hand, the Chief Justice may mean by neutrality that government restrictions on speech cannot favor certain communicative contents over others. As a general rule, this, of course, is correct, see, e.g., Police Dept. of Chicago v. Mosley. The general rule, in fact, is applicable to the facts of this case: San Diego has chosen to favor certain kinds of messages - such as onsite commercial advertising, and temporary political campaign advertisements - over others. Except to imply that the favored categories are for some reason de minimis in a constitutional sense, his dissent fails to explain why San Diego should not be held to have violated this concept of First Amendment neutrality.

And Justice Brennan's concurrence in the judgment agreed that a commercial advertising vs. other speech line was content-based:

It is one thing for a court to classify in specific cases whether commercial or noncommercial speech is involved, but quite another - and for me dispositively so - for a city to do so regularly for the purpose of deciding what messages may be communicated by way of billboards. Cities are equipped to make traditional police power decisions, not decisions based on the content of speech.

Indeed, returning to Reed, the discrimination being political signs, ideological signs, and qualifying event signs is at least as content-based as the discrimination labeled content-based in Metromedia itself (e.g., the distinction between "temporary political campaign advertisements" and other speech).

Now there's a lot to debate about the merits of Sorrell v. IMS Health, Inc.. Among other things, one can argue that content-based discrimination should be permissible within the category of commercial advertising (e.g., barring advertising for one product but not another), or against commercial advertising (e.g., allowing non-advertising speech but forbidding advertising), though IMS also involved the unresolved question "whether all speech hampered by [the statute] is commercial, as [the court's] cases have used that term." Historically, Justice Brennan and Stevens took a view broadly protective of commercial advertising, but in recent years Justices Kennedy and Thomas have been the most consistent pro-commercial-advertising-rights votes. (Chief Justice Roberts, Justice Alito and Justice Sotomayor may also be in the Kennedy/Thomas camp, but they have voted in many fewer commercial advertising cases; Justice Scalia seems to be somewhat in the middle, though he appears to have shifted from a pro-restriction view in the 1980s to a more pro-protection view today.) Perhaps this protection for commercial advertising has gone too far - but that is a different matter, and unrelated both to Reed and to the specific criticism that the Atlantic article offers with regard to the Sorrell opinion.

And of course one can also argue that the general ban on content discrimination, even outside commercial advertising, should be relaxed in various ways. Justices and scholars have debated the matter over the decades. But the argument should then focus on that question, rather than incorrectly asserting that Justice Kennedy is somehow leading a retreat from a traditional understanding, when there is no retreat, and no leadership on this point on Justice Kennedy's part.

Show Comments (0)