Increasing Top Tax Brackets Is Easier Than Increasing Revenue Over Time

Proponents of jacking top marginal income tax rates such as AOC ignore how hard it is to actually boost revenue over the long haul.

Freshman Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D–N.Y.) has floated the idea of increasing the top marginal income tax bracket to 70 percent to help pay for her "Green New Deal" programs. Ocasio-Cortez said the top rate would kick in on families making $10 million or more, a figure that covers the top 0.5 percent of Americans. The current top income tax bracket is 37 percent and kicks in at $600,000. "People are going to have to start paying their fair share in taxes," Ocasio-Cortez told 60 Minutes (for what it's worth, in 2016, the top 1 percent of income earners paid 44 percent of all income taxes).

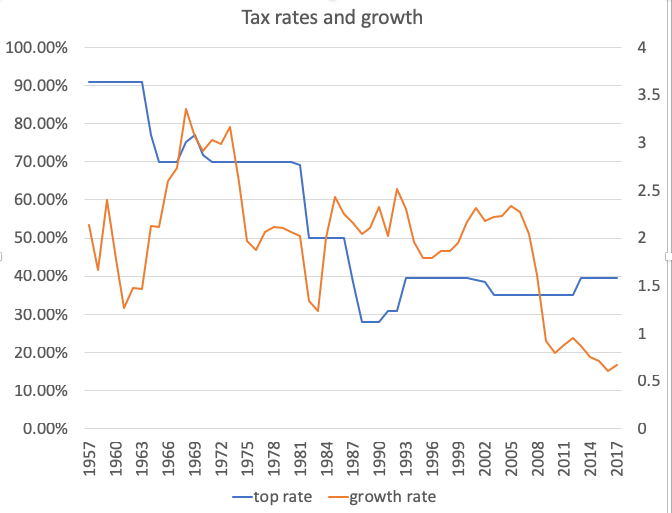

Supporters of the hike are quick to point out that in the past, top rates have ranged as high as 92 percent and, in the words of Nobel laureate and New York Times columnist Paul Krugman, the country "did just fine":

What we see is that America used to have very high tax rates on the rich — higher even than those AOC is proposing — and did just fine. Since then tax rates have come way down, and if anything the economy has done less well.

Krugman produces this chart, which plots annual economic growth against top marginal rates:

Accounting for 48 percent of the total, income taxes are the single-biggest source of revenue for the federal government, followed by payroll taxes (35 percent), and corporate taxes (9 percent). The Washington Post estimates that Ocasio-Cortez's proposal might raise about "$72 billion annually — or close to $720 billion over 10 years" while stressing "the real number is probably smaller than that, because wealthy Americans would probably find ways around paying this much-higher tax."

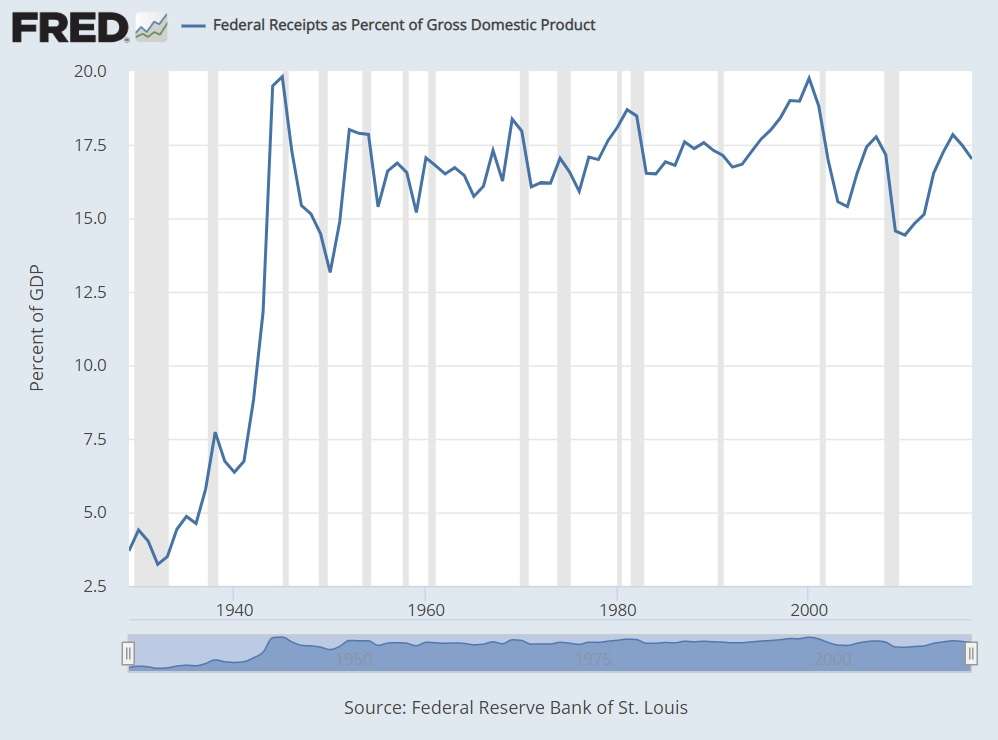

That's not a small point but it's not just rich people who find ways to avoiding tax hikes. For any number of reasons, since the end of World War II, it has proven exceptionally difficult for the federal government to substantially increase overall revenues for any period of time. The entire country, it seems, has an aversion to paying more than about 18 percent of GDP in the form of total government revenues. Despite very different income tax brackets, corporate tax policy, you name it, it's rare when the feds' take tops 18 percent for very long (recall that both Al Gore and George W. Bush campaigned on tax cuts in 2000, after a series of big-revenue years for the federal government).

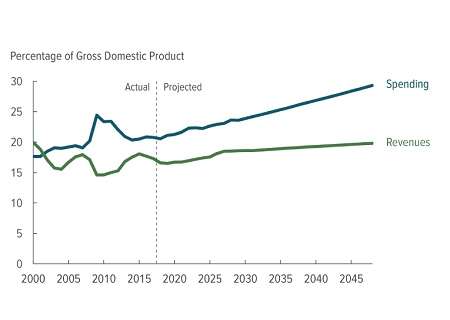

The flip side of the "remarkably stable amount of federal revenue as a percentage of GDP"? Sadly, it's the ability of the federal government to spend much more each year than it takes in via taxes and other fees.

According to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), the annual deficit will rise from about 4 percent of GDP to 9.5 percent of GDP in 2048. By then, I suspect we'll care less about the top marginal rate, if only because we'll have bigger problems to worry about.

Now that we live in a world where neither Republicans nor Democrats even pay lip service to reducing the national debt, here's a reminder why persistent deficits are so bad for the economy and other living things:

Show Comments (96)