SCOTUS Says Non-Authorized Rental Car Drivers Do Not Automatically Forfeit Their Fourth Amendment Rights

Fourth Amendment advocates score a limited victory in Byrd v. U.S.

Fourth Amendment advocates scored a limited though still important victory today when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled unanimously that non-authorized drivers of rental cars do not automatically forfeit their Fourth Amendment rights to a reasonable expectation of privacy inside such vehicles.

The case is Byrd v. United States. In 2014 a woman named Latasha Reed rented a car in New Jersey. She then gave the keys to her fiancé, Terrence Byrd. While driving the rental car in Pennsylvania, Byrd was pulled over for a possible traffic infraction. The officers on the scene asserted that because Byrd was not listed as an authorized driver on the rental agreement, they did not need to obtain his permission before searching the car—which is something that they would have needed to do had he been the authorized driver. Their subsequent search of the trunk turned up body armor and 49 bricks of heroin.

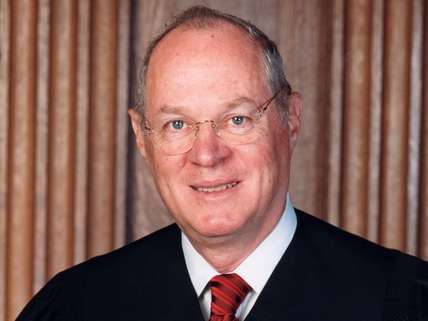

Under the federal government's theory of the case, explained Justice Anthony Kennedy in his ruling today, "drivers who are not listed on rental agreements always lack an expectation of privacy in the automobile based on the rental company's lack of authorization alone." But that position, Kennedy insisted, "rests on too restrictive a view of the Fourth Amendment's protections."

As Kennedy pointed out, "car-rental agreements are filled with long lists of restrictions. Examples include prohibitions on driving the car on unpaved roads or driving while using a handheld cellphone. Few would contend that violating provisions like these has anything to do with a driver's reasonable expectation of privacy in the rental car." Yet that contention would seem to follow naturally if the Court adopted the federal government's sweeping argument and followed it to its natural conclusion.

The Supreme Court unanimously refused to adopt the federal government's sweeping argument. "As a general rule," the Court declared, "someone in otherwise lawful possession and control of a rental car has a reasonable expectation of privacy in it even if the rental agreement does not list him or her as an authorized driver."

This counts as a win for Byrd and his lawyers. But it does not count as total victory. That's because Kennedy's ruling concluded by remanding the case back down to the lower court, which was instructed to consider two additional arguments raised by the government: first, whether the search might still be ruled legal on grounds of probable cause; and second, whether "one who intentionally uses a third party to procure a rental car by a fraudulent scheme for the purpose of committing a crime is no better situated than a car thief." In other words, Byrd still faces the real possibility of losing in his ultimate quest to have the evidence against him thrown out.

Fourth Amendment advocates, however, should generally be pleased. The upshot of today's decision is that the Supreme Court has made it a little bit more difficult for law enforcement officials to search certain vehicles without a warrant.

The Supreme Court's opinion in Byrd v. United States is available here.

Show Comments (49)