America's Sinking Public Pension Plans Are Now $1.4 Trillion Underwater

Taxpayer contributions to pension plans have doubled in the past decade, but pension debt continues to increase.

After several years of steady investment growth and higher contributions from taxpayers, most of America's public sector pension plans are still awash in red ink.

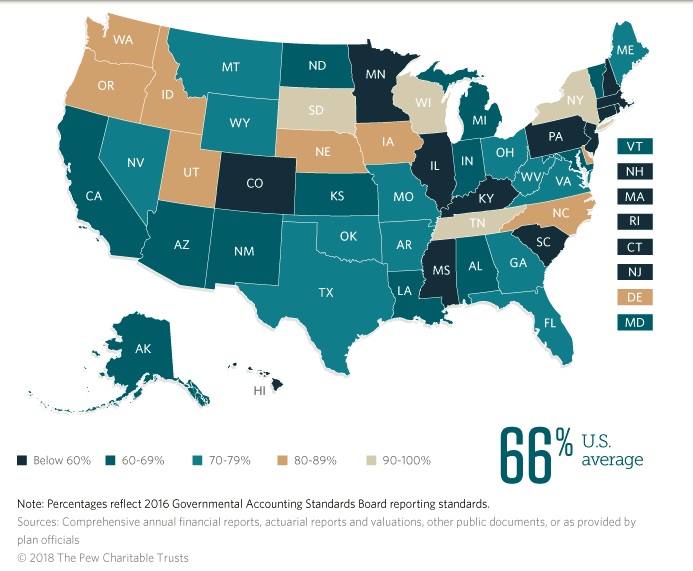

According to a new report from the Pew Charitable Trusts, the states collectively carry more than $1.4 trillion in pension debt—and only four states have at least 90 percent of the assets necessary to meet their long-term obligations to retirees. The Pew paper, which is based on states' 2016 financial reports, shows that pension debt increased by about $295 billion since the previous year, making 2016 the 15th consecutive year in which state-level pension debt increased.

The really scary part is that pension debt keeps increasing despite the fact that taxpayers' contributions to state-level pension plans have doubled as a share of state revenue in the past decade. Also worrisome: Pension plans are chasing increasingly risky investments. The gap between returns on safe investments and state pension plan investment assumptions was the highest in decades, the Pew researchers note, leaving pensions more vulnerable to market volatility and raising concerns that another downturn could drive already deeply indebted systems over a cliff.

Higher contributions from taxpayers and good returns in the market should bring well-structured pension plans back to good health. But only four states—New York, South Dakota, Tennessee, and Wisconsin—have at least 90 percent of the necessary assets to cover their retirement liabilities, Pew says.

There are two problems here. One is embedded in the very design of public sector pension plans. The other involves the politicians who are trusted to keep those plans funded properly.

The systemic problem is that pension plans generally assume unrealistic investment returns. "The median public pension plan's investments returned about 1 percent in 2016, well below the median assumption of 7.5 percent—a disparity that added about $146 billion to the debt," Pew notes. Those high assumptions also help hide the extent of the crisis. If the median assumption across all pension plans was lowered from 7.5 percent to merely 6.5 percent, states' collective pension debt would jump from $1.4 trillion to $4.4 trillion. Assuming 7.5 percent returns every year in perpetuity allows states to pretend they have more future assets than they likely will.

The political problem is that officials have underfunded pension plans for years. Taxpayer contributions have increased dramatically since the Great Recession, yet many states still fail to make the equivalent of a minimum credit card payment each year. "Only 27 states contributed enough in 2016 to expect their funding gaps to decline if actuarial assumptions were met," says the Pew report.

And there was a wide range in states' contributions, with some paying more than 30 percent above that minimum amount while others fell more than 20 percent behind. Making that minimum contribution is not enough to ensure that plans won't accumulate more debt—that can happen anyway if investments fall short of their lofty targets, as they often do—but falling short of the minimum virtually guarantees that a state will fall farther behind.

Of course, every dollar spend on public pensions is a dollar that state's can't spend on roads, schools, or anything else. That's the heart of the political problem driving America's pension plans: Adequately funding pensions is expensive, and politicians would rather spend limited tax dollars elsewhere.

There is no one-size-fits-all solution to the pension crisis, as every state (and city) has unique budgetary situations and pension plans have different underlying sets of assumptions. In Wisconsin, where state pension plans are 99 percent funded, there is a great deal more flexibility in future choices than in New Jersey, where only 33 percent of the state plans' liabilities are covered.

Removing politicians from the equation is a major benefit of transitioning away from traditional defined benefit pension plans and into 401(k)-style plans where individual workers control their retirement accounts. That also helps get taxpayers off the hook for having to make up the difference when markets or political will falls short of pension plans' expectations.

But for now, taxpayers will continue to pay more to finance public sector workers' retirements—and another recession could be a catastrophic blow for all involved.

Show Comments (62)