In Pennsylvania, Prohibition Is Finally Losing Its Grip

Keystone State alcohol regulations were among the strictest in the nation. Now the commonwealth is on the brink of fully liberalizing its liquor laws.

For decades, Pennsylvania has had some of the strangest rules about where, and how, you could buy alcohol.

I knew them well. Having grown up in Pennsylvania and returned there for a few years after college, I got used to explaining those rules—"I know, I know, it's crazy, but we have to stop here to get the beer, and then we have to drive across town to get the whiskey"—to out-of-staters who would come to visit. Every state has weird rules about liquor, but everyone could agree that Pennsylvania's were the worst.

Beer was only available from distributors and you couldn't get anything smaller than a full case (24 bottles or cans), unless you went to a bar that had a license to sell six-packs to-go and paid a hefty premium for the convenience. Wine and spirits were only available from one of the 600 or so state-owned-and-operated liquor stores. In rural parts of the state, that could mean driving half an hour or more out of the way, since the state stores are clustered in cities and suburbs.

That's changing. In fact, the changes have come so quickly that someone who moved out of the state as recently as 2013—as I did—can be stunned when returning home to visit friends and family. Now, I'm the confused out-of-stater who needs an explanation about where you can go to buy which products.

Many of the state's rules were legacies of Prohibition. But they began changing in the early 2010s, when a few large grocery stores began exploiting a loophole in state law that let them operate with a restaurant license and sell six-packs of beer. Unsurprisingly, the idea proved popular. Even as political efforts at broader booze reforms went nowhere in Harrisburg, the state capital, it became gradually easier to buy smaller quantities of beer. Other changes in the past few years made it legal for beer distributors to sell 12-packs, then six-packs. After a major political compromise in 2016, it's now possible to buy beer and wine at grocery stores. A limited number of large convenience stores attached to gas stations can also sell beer to-go, after a longstanding prohibition on selling booze and gasoline at the same spot was lifted last year.

For all the changes, there are still two big, related problems.

First, liberalized rules for the purchasing of wine and beer are good, but the changes have ignored hard liquor, which accounts for 53 percent of all sales in Pennsylvania's "Fine Wine and Good Spirits" shops. For whiskey, tequila, rum, and so on, the only option is taking a trip to a state-controlled liquor store and paying the state-determined price. The second problem is that it's still impossible to buy all types of alcohol in a single location, because the state-run liquor stores can sell wine and spirits, but not beer, while beer distributors and grocery stores can sell suds and vino, but none of the hard stuff.

Special interests on both sides of the aisle—primarily the public-sector unions representing state liquor-store employees on the left, and on the right, the beer-selling businesses unwilling to give up their special privileges and anticompetitive markets—helped keep Pennsylvania's awkward, anachronistic system in place for decades. But they've seen their influence wane, ever so slightly, in the past few years. A shifting political climate and an out-of-state grocery store chain fractured the delicate balance, and a Republican speaker of the state House and Democratic governor have done their part to liberalize the state's alcohol regulations.

Finally, Pennsylvania might be on the brink of recovering from an 83-year hangover.

--

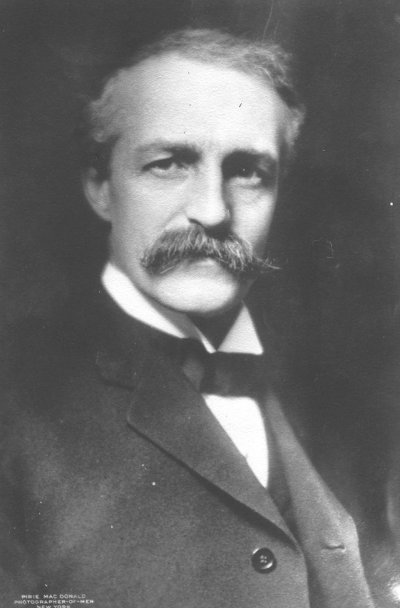

When Prohibition was shoveled into the ashbin of history in 1933, Pennsylvania Gov. Gifford Pinchot was not a fan. An outspoken teetotaler and progressive Republican who thought liquor contributed to political corruption, Pinchot believed that "Prohibition at its worst has been better than booze at its best," and he wasn't afraid to keep imposing his beliefs on the people of Pennsylvania.

There wasn't political support for a continued state-level ban on alcohol after the passage of the 21st Amendment, so Pinchot negotiated what he saw as the next best thing: a state-run liquor system that would be both wholesaler and distributor. During a special session of the state legislature called by the governor after it became obvious Prohibition's days were numbered, he convinced lawmakers to approve a state liquor system that would discourage the purchase of alcoholic beverages "by making it as inconvenient and expensive as possible."

The 21st Amendment wasn't officially ratified until December 5, 1933. Less than a week earlier, on November 28, the state Senate had taken the final vote on creating the Pennsylvania Liquor Control Board (PLCB), approving it by 33–14. Pinchot signed the bill the very next day.

Pinchot left office in 1935. He died in 1946. His state-run liquor store monopoly would remain virtually unchallenged for another 30 years.

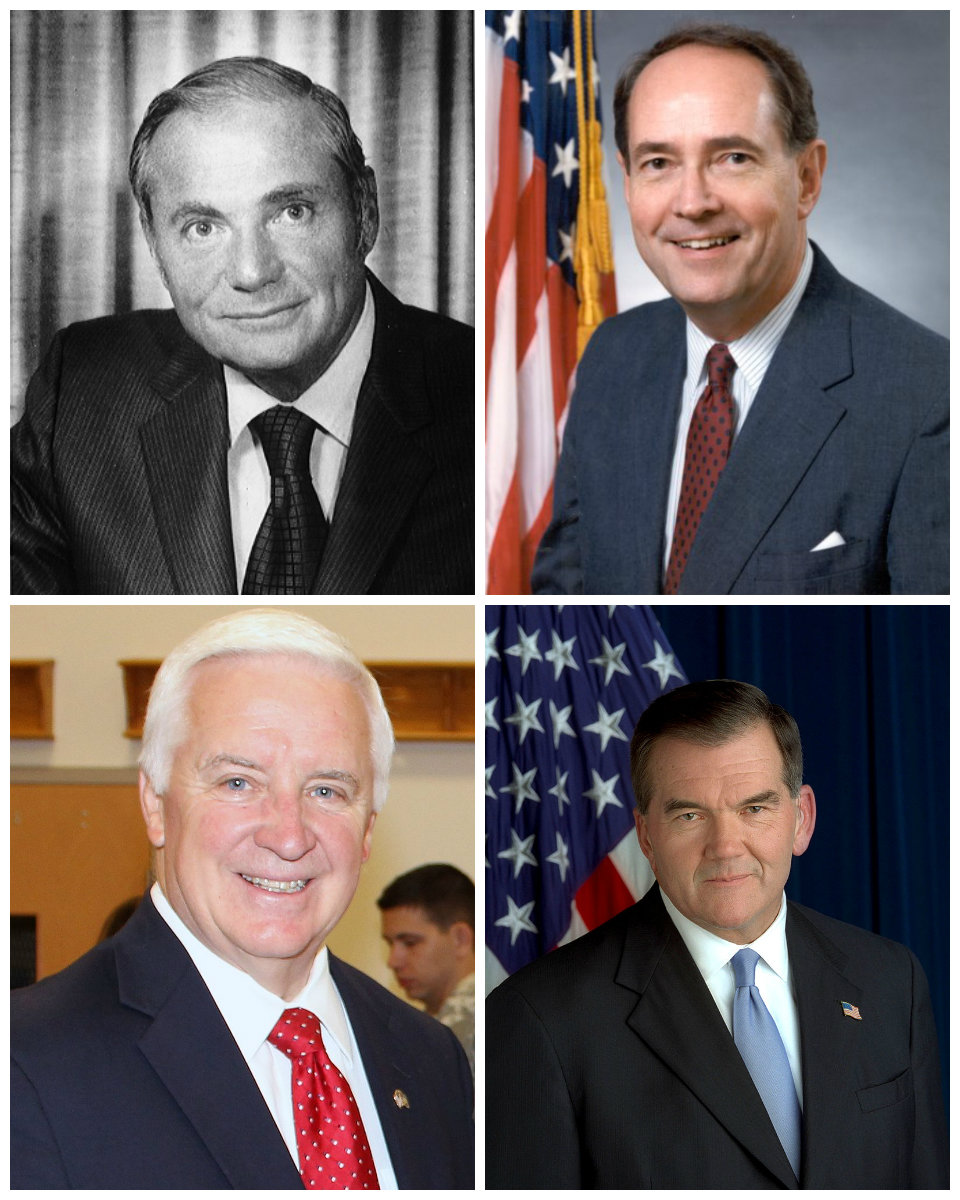

In 1974, Gov. Milton Shapp made the first serious effort at privatizing the system. Those reforms were blocked, as the Delaware County Daily Times reported at the time, by opposition from state store clerks, beer distributors, Philadelphia-based distilleries, and the heads of the PLCB.

Each of those groups had their own interests to protect, and those protectionist tendencies have changed little in the decades since. The workers in the state stores are members of public-sector unions that hold significant sway over policy making in Harrisburg and don't like to see the number of their members reduced.

Beer distributors fear the loss of their own fenced-off market and greater competition if other private-sector retailers gain the right to sell booze. Pennsylvania-based liquor and wine manufacturers see the PLCB's role as the sole liquor wholesaler in the state as advantageous, since it can limit competition from out-of-state wineries and distilleries. The bureaucrats running the PLCB don't want to lose their jobs.

And then there's the remaining influence of the temperance movement.

"Alcohol is a drug—a dangerous drug," Rep. Stanley Kester, chairman of the House Liquor Control Committee at the time, told the Daily Times in 1974 after reviewing Shapp's privatization plan. "The problem is that it's here to stay, and if you support the governor's proposal, you're talking about increasing the amount of alcohol."

That same combination of political self-interest and social paternalism sank subsequent efforts at privatization launched by Gov. Dick Thornburgh in the 1980s, by Gov. Tom Ridge in the 1990s, and by Gov. Tom Corbett in the early 2010s. Without sweeping reforms to how the state system worked, changes were as slow as you'd expect from a bureaucracy left to its own devices. It wasn't until the late 1980s that the PLCB finally did away with its post office–style stores that required customers to order their alcohol at a counter and wait for an employee to fetch it from a back room. An ill-fated experiment with "wine vending machines" in the mid-2000s cost the state millions of dollars in the name of "modernizing" the liquor-buying experience.

And in 2014, in what might be the perfect illustration of how screwy Pennsylvania's liquor laws could somtimes be, a judge in the state ordered more than 1,300 bottles of wine poured down the drain simply because they were illegally imported. Arthur Goldman, the Pennsylvania man behind the illegal scheme to circumvent the PLCB's monopoly, offered to sell the wine and give the profits to a Chester County Hospital, but he was prohibited from doing so (though he did get to keep 1,000 bottles of his exclusive, and expensive, collection).

Until last year, Pennsylvania was one of only two places where the state government had total control over the retail sales of wine and spirits. (Utah is the other.)

"In my view, the principal roadblock to reform has traditionally been an odd coalition of state store employee unions, fundamentalist anti-alcohol groups and organizations such as Mothers Against Drunk Driving, all of which perceive that they have legitimate interests which are not susceptible to statewide budgetary considerations," Thornburgh, the former governor who now works as an attorney in Washington, D.C., told the Harrisburg Patriot-News in 2009.

"It would take some courageous leadership to stare down this combination, something I do not see in the Commonwealth today," he predicted.

--

As it turned out, it wasn't political leaders who cracked the special interests' hold on Pennsylvania's weird liquor laws. It was clever retailers.

In 2009, a Rochester, New York, grocery store chain, which was expanding its presence in Pennsylvania, began exploiting a loophole in the state's alcohol sales rules. By building separate entrances and check-out lines, along with offering hot food and on-location seating, Wegman's was able to license part of its grocery stores as restaurants, thus allowing the sale of six-packs of beer.

"People have come in and said, 'I'm in heaven,'" Kevin Russell, store manager at the Wegman's location in Downingtown, told the Delaware County Daily Times shortly after the first Wegman's opened there in 2009.

The special interests weren't so enthusiastic. The Pennsylvania Malt Beverage Distributors Association, which represents beer distributors in the state, took the grocery chain to court in an effort to maintain its members' monopoly on beer sales. The state Supreme Court eventually sided with Wegman's, and soon other grocery stores were using the same tactic to sell six-packs of beer.

Wegman's innovation coincided with a renewed push in the state legislature for writing better rules for booze in Pennsylvania. For the first time, the special interests defending the status quo were on the defensive.

Republicans swept into control of the state government after the 2010 elections, and newly elected Republican Gov. Tom Corbett and then–House Majority Leader Mike Turzai (R–Allegheny) put liquor privatization near the top of the agenda, promising to succeed where others had failed. During Corbett's four years in office, there were annual efforts to rewrite the state's liquor laws and divest state control over wholesale and retail liquor sales. They never got closer than in June 2013, when a full privatization plan fell just short of passing during that year's budget negotiations.

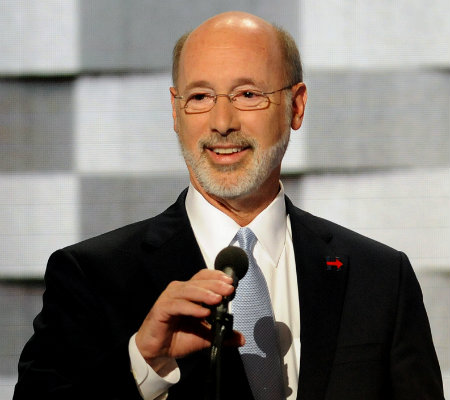

Corbett lost re-election to a Democrat, current Gov. Tom Wolf, in 2014. That seemed to initially cool talk of privatizing the liquor system, since Democrats and their labor union allies generally oppose the idea. Instead, quite the opposite has happened. Wolf and Republican leaders in the state legislature have not seen eye-to-eye on much else (Pennsylvania went more than nine months without a budget during Wolf's first year in office), but liquor has been the notable exception. While Wolf did veto a GOP-passed liquor privatization bill in 2015, the governor signed a different bill last year transforming the way Pennsylvanians buy booze.

That law, Act 39 of 2016, allows bars and restaurants (including those "restaurants" inside grocery stores) to sell wine to-go, allows convenience stores attached to gas stations to sell beer, and allows beer distributors to sell six-packs for the first time (earlier reforms approved by the Wolf administration had allowed the sale of 12-packs in addition to the traditional 24-packs).

"One huge plus is you don't have to spend $70 to try out a new beer," says Jordan Weikel, a Berks County resident, of the changes that let Pennsylvanians buy smaller quanties of beer than a 24-bottle case.

Even with the changes, the system is awkward and complicated. Purchasing beer or wine at a grocery store still requires using separate check-out lines for food and alcohol.

"When you are picking up a pizza and a beer for dinner, you have to wait in two different lines," says Kate DiCicco, who lives in Philadelphia. "You have to strategize how to get warm-ish beer but a fresh cooked pizza or cold beer with the chance of knocking your warm gooey pizza during the Check-Out Biathlon."

And if you want to get a bottle of tequila to go with that pizza—no, that's actually not a bad combination at all—you still have to make another stop at one of the state-run liquor stores, because liquor was left out of last year's reforms.

This year—maybe—that could finally change.

"The idea here is to increase consumer choice and convenience," says state Rep. Mike Reece, a Republican lawmaker from the hilly Pittsburgh suburbs of Westmoreland County. He's the lead sponsor on one of four major liquor reforms that cleared the state House this week. While each of the bills offer something to like, Reece's proposal—H.B. 438—is the one that probably holds the most interest for consumers, because it would allow liquor to be sold alongside beer and wine in any of Pennsylvania's grocery stores and beer distributors that pay for the license to do so.

At last, the dream of a one-stop-shop for all types of alcohol could be realized.

"I think most elected officials recognize that the people who elected us want this, they want to be able to get everything in the same place," Reece tells Reason. "I think that's the direction we've been moving for a few years."

His proposal would open up private retail sales for liquor, but would keep the state as a monopolistic wholesaler. Retailers would have to purchase all liquor through the PLCB and would pay a 2 percent tax to the state on those purchases. That's meant to respond to the argument that privatization would eliminate an important revenue stream for the state budget. According to the PLCB, liquor sales and taxes accounted for more than $600 million in last year's state budget. That money funds enforcement activities run by the state police, along with drug and alcohol abuse treatment programs.

In theory, if all 10,000-plus newly eligible locations pony up the $2,000 for a permit to sell liquor, the state could make more than $21 million up front, Reece says.

--

"People in general have been for more privatization," says Terry Madonna, a professor of political science at Franklin and Marshall College in Lancaster who conducts semiannual polls on Pennsylvanians' political and policy preferences.

That's probably because it's so difficult to get liquor in Pennsylvania. According to data from the Distilled Spirits Council of America, which favors privatization in Pennsylvania, there are an average of 3.8 liquor retailers (meaning any place where it's possible to buy a bottle of hard alcohol) per 10,000 people in the United States. In states where the government exercises control over liquor sales, either at the wholesale or at the retail level, there are about 1.76 outlets per 10,000 people.

In Pennsylvania, there are 0.67 liquor stores for every 10,000 people. The state would have to add more than 900 new liquor stores just to approach the national average.

That's unlikely to happen without some form of privatization. If not by allowing grocery stores to sell liquor alongside beer and wine, it could happen by opening up so-called "agency shops"—privately run liquor stores allowed to compete with the state-run wine and spirit shops. That's what several other states, including New Hampshire and Ohio, do.

Pennsylvania could join that group. Along with Reece's bill, the state House this week also approved H.B. 991, which would allow the creation of privately owned retail liquor stores to compete with the state-run ones. The PLCB would maintain monopoly control over the wholesale level, but the retail monopoly would be gone. Consumers would enjoy greater convenience, the state's economy could benefit from the creation of new jobs, and the state budget might even get a boost from additional tax revenue if liquor sales increase.

Two other bills, both sponsored by Turzai, the Republican speaker of the House, also cleared the lower chamber this week. One of them (H.B. 975) would allow wine retailers and importers to have greater flexibility over supply and pricing, effectively chipping away at the state's wholesale monopoly, while the other (H.B. 1075) would completely abolish that monopoly by fully divesting the state's wholesale control over wine and liquor sales to a private company.

Together, the package of bills are meant to give consumers and businesses greater freedom to buy and sell alcohol with less state control. But, to varying degrees, they would threaten the jobs of the 5,000 or so public union members who work at the PLCB and in the state-run liquor stores.

Wendell Young, president of the United Food and Commercial Workers Local 1776, which represents most of the state's liquor-store employees, called the Republican proposals "a disappointing but expected effort" to "score a quick buck on new licenses."

"The state system of liquor sales is already a successful model providing regular profits and good jobs," Young said.

Massive Republican majorities in the state House and state Senate—the largest margins enjoyed by either party in more than 50 years in Pennsylvania—and the general rightward shift of the GOP have weakened union influence in Harrisburg, but it remains a significant factor. Wolf, the governor, took the lead on earlier reforms like allowing beer distributors to break up cases and sell six-packs, but those changes did not bring the former businessman into a direct confrontation with the labor unions. Supporting liquor reforms would.

That's why "the difficulty for Wolf, in the long run, is with organized labor," says Madonna.

Further complicating things is the prospect of a tough re-election fight in 2018—Wolf is the only Democratic governor of a state won by President Donald Trump. He'll want support from the politically powerful labor unions.

Wolf says he's against the proposed expansion of private liquor sales, and says the state needs more time to gauge whether last year's privatization of wine sales is working.

"The governor does not support these bills," J.J. Abbott, Wolf's press secretary, tells Reason via email. "He is currently focused on allowing the consumer-centric reforms enacted last year to be fully implemented and ensuring the PLCB is working to maximize returns and consumer convenience."

"I get that. I respect it," Reece says. "I just disagree with the notion that the state should be in the business of selling alcohol."

Even though it's only April, all eyes in Harrisburg are already looking ahead to June, when the state budget gets negotiated. Major policy items usually rise or fall during those crucial weeks, and Reece is hopeful the Republican-controlled legislature will muster the votes for his liquor bill in order to give it a seat "at the table for discussion during the budget talks.

--

Ernest Hemingway observed that bankruptcy (or getting drunk, for that matter) is something that happens gradually, then all at once. The same, it seems, could be true of the collapse of privileges bestowed by government that run counter to the will of the people and common sense.

Pennsylvania's state-run liquor system has survived more than a half-dozen attempts, by member of both parties, to kill it. Ironically, a system created by a governor who feared that easy access to alcohol would contribute to political corruption has endured in large part because of the power of special interests in the state government.

The system, and those special interests, may stave off the final blow this year, but something has changed—something that goes beyond the ability to buy a six-pack and a bottle of wine in a grocery store, though I'm not sure I've gotten over the wonder of being able to do that.

I asked Steve Miskin, who in his role as Turzai's spokesman since 2010 has probably answered more questions from reporters about possible changes to Pennsylvania's liquor laws than any single person in the history of the commonwealth, why the pace of reform has quickened in recent years. It's the hard work of Republican members in the state House, who refused to let the issue drop even when a Democratic governor took over, he says, like any good spokesman should. Fine. But what else?

"The timing was right," he says. "This is what the people want."

Charlie Gerow, a Harrisburg-based Republican political consultant, says it wasn't just an accident of history. The bizarre mix of "prohibitionism and socialism" survived previous privatization efforts despite public support for reform, he argues, because governors like Thornburgh and Ridge saw their privatization efforts fail and moved on to other issues. Turzai has not.

It's true. Since becoming majority leader in 2010, Turzai has made liquor privatization his biggest issue year after year. When the liquor privatization bill was on the brink of passing in 2013, I glimpsed Turzai as he left the meeting where Corbett decided not to press the issue. The governor could have asked Senate leaders to try again; they were refusing to pass the liquor bill unless the state House voted for more spending on roads and bridges, and Turzai was unable to corrale the necessary votes to get it done. He was crushed. The next year, he could have moved on to something else. Instead, he was trying again.

That tenacity might be finally paying off.

"His dogged determination to get rid of the system is the single biggest factor in the successes that have already occurred," Gerow says, "and of the ones yet to come."

If Pinchot gets the blame for creating the liquor system, despite the fact that plenty of lawmakers went along with it, then Turzai probably deserves to be remembered in the same way when it all, eventually, inevitably, comes down. Give some credit to Wegman's, too, for landing the first critical blow that weakened the left-right alliance of beer distributors and public sector unions.

It's hard to say what will happen between now and the end of June. The state Senate has all four liquor bills and the state budget bill (which the state House passed earlier this month), and Wolf will get to have his say as well.

Still, there's a better chance in 2017 than at any other time in the 83 years since the end of Prohibition. Even if Pennsylvania's state-run liquor system probably isn't going to hear last call anytime soon, it might at least get a bit more competition.

Madonna, who has closely followed state politics for decades in Pennsylvania, admits that the state has passed a tipping point in the reform of its arcane alcohol laws, though he admits he's not sure what things will look like in a few years. One thing is fairly clear, though, he says: The state is finally putting the ghost of Gov. Gifford Pinchot to rest

"I think it's virtually inevitable now," Madonna says, "that Pennsylvania is moving towards the privatization of the retail sales of alcohol—all alcohol."

Show Comments (22)