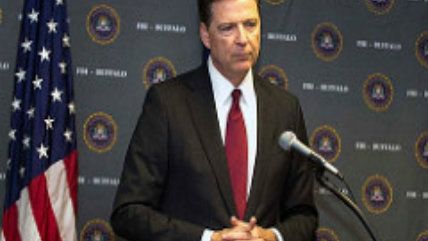

'No Such Thing as Absolute Privacy in America,' Warns FBI Director Comey

Government can "invade our private spaces" if it has a "good reason."

Earlier this week, FBI Director James Comey spoke at the Boston Conference on Cyber Security at Boston College and addressed the growth of cyber threats. While the agency head explained that "cybersecurity is a priority for every enterprise in the United States at all levels," he also made some chilling statements that should give every American pause.

"There is no such thing as absolute privacy in America," Comey announced at the conference, Politico reported. "There is no place in America outside of judicial reach."

This comes on the heels of a Wikileaks dump that revealed the CIA is working on hacks into everything from smart televisions to cars. The reality of a mass surveillance state has been apparent at least since then–National Security Agency contractor Edward Snowden leaked information in 2013 that the organization was spying on the public, so admissions like these from the intelligence community should come as no surprise. Yet the candidness with which Comey admits that Americans' privacy is circumscribed is striking.

He acknowledged that the law says "all of us have a reasonable expectation of privacy in our homes, in our cars, and in our devices," but provided a nice little caveat that if it has a "good reason," the state can nonetheless "invade our private spaces."

"Even our memories aren't private," Comey added, according to Politico. "Any of us can be compelled to say what we saw…In appropriate circumstances, a judge can compel any of us to testify in court on those private communications."

Back in 2015, a Pew Research poll found Americans were not nearly as concerned as you might think about the government spying on them. Some 54 percent were not very or not at all concerned about officials snooping on their emails; 53 percent felt the same way about their search engine data. Even when it came to cellphones, 54 percent were not concerned.

Many participants explained that they were not worried about government surveillance programs as long as they were helpful in preventing terrorist attacks or criminal activity. It appears, in this instance anyway, that a substantial segment of the population prefers security to liberty.

Perhaps the latest Wikileaks release will lead to more substantive discussions about privacy and mass surveillance, but as Reason's Scott Shackford pointed out in his article about the president's recent wiretapping claims, it can be hard to get people to look beyond their politics. He wrote:

There is plenty to discuss about problems with how surveillance authorities are granted here in the United States—the incidental collection of our own private data, the opaqueness of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISC), and the potential for intelligence sharing to be abused domestically to bypass the warrant requirements of the Fourth Amendment.

But none of those policy issues are being brought up in this fight at all. It's all about Trump vs. President Barack Obama. This fight just turns real surveillance issues into political intrigue and just another tool in the battle over who controls the executive branch. Everything about this issue has been and will continue to be analyzed in the terms of what it all means for Trump—and only Trump.

A reminder for anyone who will be in Austin this weekend that Shackford will be discussing the future of legislating on digital privacy with experts from the Fourth Amendment Caucus, the American Civil Liberties Union, and the R Street Institute at South by Southwest tomorrow. Stop by and see him.

Show Comments (62)