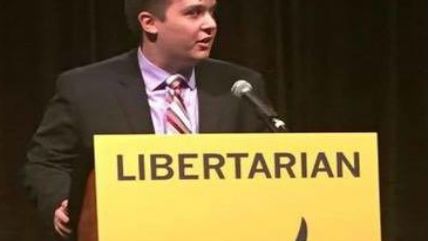

Florida Senate Candidate Bears Any Burden for the Libertarian Party

Paul Stanton deals with debate disappointments, state party sourness, and presidential ticket travails, and fights his way to tomorrow's electoral finish line.

Paul Stanton is the Libertarian Party's candidate for federal Senate in Florida, running against incumbent Republican Marco Rubio and Democratic challenger (and former Republican himself) Patrick Murphy. While Stanton hasn't been included in tons of polls, in a couple he hit very high numbers for a Libertarian running against two major party candidates: 9 percent and 10 percent in two September Public Policy Polling (PPP) polls.

By one reasonable interpretation of the stated eligibility rules for a late October Senate candidate debate sponsored by Leadership Florida and the Florida Press Association, Stanton should have gotten in.

But after being asked to consider the matter formally, the debate hosts said no, Stanton wasn't getting in, based on disagreements over the "independence" of PPP since an organization called VoteVets that had given services in support of rival Murphy had paid for the poll, and interpreting a contradiction in their stated margin of error against Stanton. [correction: the post originally and mistakenly appeared without that italicized clause]

Stanton complained in strong terms, suggesting that it was possible they were violating a Federal Election Commission rule that prohibited mere major-partyhood from being the decisive "objective" criterion for a debate invitation. A different independent candidate, Steven Machat, did sue over his exclusion.

In a phone interview with Stanton this afternoon, he noted that while he had some idle thoughts about using the law against the debate hosts, in the end he could not: "I don't think those laws should exist, so it was: do I stand on principle or go for blood? And I couldn't in the end use government force and coercion to accomplish a political goal. It would be a violation of everything I stand for."

Stanton does admit, not too glumly, that the failure to get into the debate in October was a huge blow to his chances to really break out and get noticed. Other debates he might have been in, his major party challengers just refused to go to. They were not going to help legitimize the Libertarian Party.

Hearing Stanton discuss some of what an outsider might consider the ups and downs, with lots of downs, of his Senate run was a curious experience: so much of what he said struck me as such a heap of annoyance and unpleasantness my own sense of disappointment overwhelmed me on his behalf.

But I wasn't getting that bad attitude from him. Stanton's still very pleased with what polling data he has, though he credits how well he seems to be doing to the "political environment" of unhappiness with Rubio and Murphy. "I'm not pretending I'm some great hero everyone wants to rally behind."

The debate exclusion was far from the first problem Stanton had. The Libertarian Florida Senate race got off to a weird start last year, when the only person publicly vying for the spot in the primary was Augustus Sol Invictus, a loud and proud black magician, goat sacrificer, fomenter of armed revolution, admirer of the trappings of fascism, and friend and lawyer to white identity groups.

The L.P. has no power over a registered voter with the Party jumping through the state's hoops to be on the primary ballot, and the Party lost its then-state chair Adrian Wyllie over what he saw as insufficient willingness on the Party's executive committee's part to disavow and boot Invictus. You see, they didn't feel he'd done anything that violated the L.P.'s "non aggression principle," that is, he hadn't directly, physically damaged anyone's person or property with his peculiar beliefs.

Stanton entered the primary, after coughing up $10 grand, because he couldn't quite bear seeing Invictus be the standardbearer of his Party. Stanton was a fresh convert, brought in via Gary Johnson's 2012 presidential run. "I ran because no one was representing libertarian principles," Stanton says. He especially wanted a peace candidate, and Invictus openly celebrated war. He beat Invictus, 74-26 percent, in the August primary.

You can beat a rival candidate, but it's harder to beat the world's half-formed vague impressions. Thanks to how mediagenically colorful Invictus was, when Stanton the winner went out in the world as the actual Senate candidate for the Libertarian Party in Florida, lots of people he'd run into would "ask about goats and white supremacy."

Far from the advantage of positive branding a candidate might want out of a Party, "it became a detriment" because Invictus had managed to work his way into so many people's consciousness as the representative of the Florida L.P. Stanton says he knows of other downticket candidates in Florida who abandoned the L.P. label they would otherwise have embraced because of Invictus.

That wasn't all. At least a couple of Invictus' loyalists got on the state Party's executive committee, and Stanton thinks that might be part of the reason he hasn't gotten what he considers a high level of support from the Party. Invictus' former campaign manager, Stanton says, would "like" on Facebook violent threats against him. So, what did the Party do for him? Well, some county affiliates issue voter guides, and some of them listed him. But he isn't sure that they always do so much to get those guides out there.

Stanton has been working a more than full-time job as a computer programmer and data analyzer for Frontier Communications, navigating an $11 billion acquisition for the company, while also running for Senate.

He did all the things: "traveled around the state, pretty much all the state except Jacksonville, almost every weekend went out to do something, different political rallies, Jill Stein, Adam Kokesh, meet people and whatnot." An old army buddy, Jon Warburton, came down from Idaho, as a volunteer, to manage the campaign. He asked lots of people face to face for money, and drew around $20,000, though he hated asking. "It was hell to do. I don't like begging people for money. I work for a living, and here I am panhandling." Half of that money went to the primary filing fee, though the state's rules involve kicking back some of it to the Party itself, which kicked back its approximately $3,000 portion back to Stanton's campaign.

His messaging front and centers such perceived "left" libertarian issues as peace, the drug war, and poverty. As he explains himself on his web site:

As Senator, he will advance the principle of non-aggression, seeking to end the United States involvements in the Middle East and mitigating the harm we have already caused. Additionally, he advocates for an end to the "War on Drugs" and incarceration of users, and instead advocates for treatment and education for those who are addicted. He demands an overhaul of the federal tax system, where even those who are poor are still overburdened with taxes on the fruits of their labors through a "War on the Poor."

He is enough of a data hound that getting voter lists from the state and crunching data to get good mailing lists for begging Libertarians for money and informing them of his campaign was easy. He started to find it hard to sell big picture Libertarian principles face to face. Stanton thought through out loud in our interview how to get people to understand that, say, wanting drugs to be legal wasn't cover for some nefarious desire to do drugs or have one's drugged-out associates running wild in the streets. But principles can be harder to grasp for some voters than policy.

He's never done an illicit drug, ever, insists this veteran of stints in Iraq in the mid-'00s, working in the "triangle of death" as personal security for a bomb squad with the 101st Airborne. He did once have to rescue a friend trapped by debt and violence in a "drug house," unable to seek any official help because of the whole drug angle. That experience helped make the drug war a very big issue to Stanton.

But mostly this combat veteran cares about peace. His vet status "makes it harder for people to call me a whiny scared hippie," though he says he's the kind of veteran who does not like to "use war vet status as an armor."

Nor does he want to talk that much about the presidential ticket, except to insist he is certainly voting for Johnson, far and away the best choice, he makes sure I understand. Still, Stanton was a bit let down that the presidential campaign stonewalled any attempt on his part to speak to the crowds at Johnson and/or Weld's Florida events.

That's even though, Stanton notes, they had no problem appearing on stages with Republicans there and elsewhere. All he kept being told was they didn't have time to properly vet the downticket L.P. candidates and thus couldn't take any chances.

None of this is delivered like he's complaining; it's just the facts. I asked him about all the details of his Senate race, and he told me. It sounds like the sort of needless stress and strain that might break a man, but he's not at all discouraged, near as I could tell. It helps that he believes in this cause; he can't see whatever troubles it involved as needless. Peace and liberty are important, and someone has to step up for them.

I ask him a question, meant to be about his vision of the Party's near future, about how the next few years will be affected by what might happen tomorrow, what the Party's situation in 2020 might be like depending on if Trump or Clinton won.

He interprets the question, rightly enough, as about his Senate race.

"Are you asking me if I'm going to run for re-election? Well, I have not decided yet. I'll have to ask my family."

He's being sly, no doubt. At the start of our conversation, he gave a more sober guess of 5-6 percent for himself, which would constitute half a million votes in that vast swampy state.

Regardless, that ability to either hotly believe in victory or dryly accept loss is the beating heart of the modern Libertarian candidate. No matter what happens, Stanton's not done.

"I plan, since I do data for a living, to help the Party with voter data, and I'm treasurer of the Volusia County [branch of the L.P.] and will focus more on local issues." If he can't do foreign policy, he likes local issues more. But he's sticking around no matter what.

"It's my party, and my movement. It's not like I own it, but I'm part of it, and why would I want to surrender the ideas of anti-violence and peace and civil liberties?"

Show Comments (92)