How Prohibition Causes Deaths From Fentanyl-Spiked Heroin

The more successful drug warriors are, the more dangerous drugs become.

Remember the guy who bought 80-proof vodka that turned out to be 190-proof Everclear and died from alcohol poisoning? Probably not, because that sort of thing almost never happens in a legal drug market, where merchants or manufacturers who made such a substitution, whether deliberately or accidentally, would face potentially ruinous economic and legal consequences. In a black market, by contrast, customers frequently get something different from what they thought they were buying: something weaker, something stronger, or some other substance entirely. As The Washington Post notes in a story about fentanyl-laced heroin, the results can be fatal.

Fentanyl, a synthetic painkiller, is something like 40 times as strong as pure heroin. Heroin dealers therefore have been known to spike their product with fentanyl from black-market laboratories, giving it an extra kick that partly makes up for the dilution that occurs between production and retail sale. Last March, the Post notes, "the DEA issued a nationwide health alert on fentanyl, reporting that state and local drug labs reported seeing 3,344 fentanyl samples in 2014, up from 942 in 2013." The Post cites three fatal overdoses involving fentanyl-spiked heroin in New York and Connecticut, plus other cases where heroin users "had to be resuscitated at hospitals." It reports that "the last major outbreak of fentanyl-related deaths began in 2005 and lasted for two years, killing more than 1,000 people."

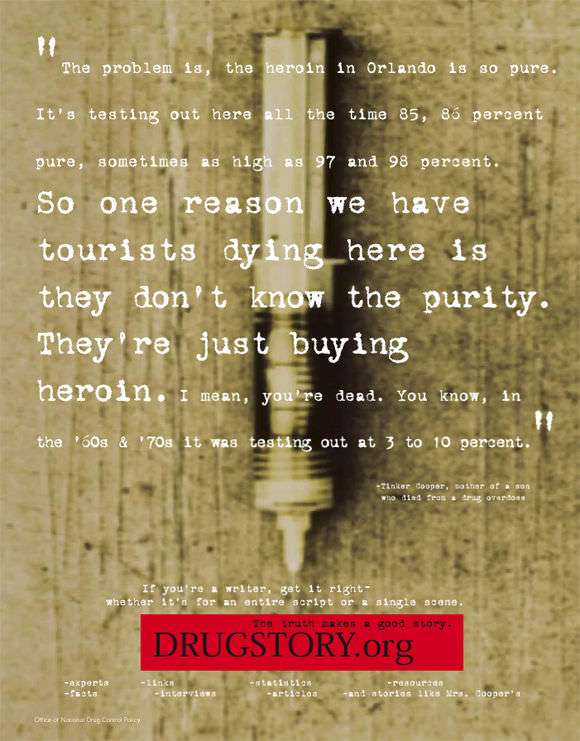

Although such fatalities are commonly called "drug-related deaths," they are more appropriately viewed as prohibition-related deaths. The artificially high prices and profits created by prohibition give dealers a strong incentive to dilute their products, and the black market's lack of legal accountability allows them to do so. If they go too far and customers start to balk, adding a little fentanyl is a cheap, easy, and occasionally lethal solution. Variations in heroin purity can have similar consequences, as highlighted by an old government-sponsored anti-drug ad (left) that quotes the mother of a heroin user who died from an overdose: "The problem is, the heroin in Orlando is so pure….One reason we have tourists dying here is they don't know the purity."

Prohibition created the hazard of unpredictable potency, and enforcing prohibition, to the extent that it has any effect at all, exacerbates the problem. Drug warriors commonly cite lower potency as a sign of success, equivalent to an increase in price for heroin of the same strength. Taking them at their word, effective enforcement leads heroin users to take larger doses, a habit that can be deadly when they encounter an unusually potent batch. Effective enforcement also means that dealers are more likely to mix fentanyl into their heroin (or lavamisole into their cocaine), so it magnifies the dangers that users face from unadvertised ingredients.

Although you can call such effects unintended, they are by now anything but surprising, and they happen to dovetail with prohibitionists' avowed goal of discouraging drug use. The more dangerously unpredictable drugs are, the less likely people are to use them. That calculation, of course, sacrifices the interests (and sometimes the lives) of undeterred drug users for the sake of protecting more risk-averse people from their own bad decisions. But that is what prohibition is all about.

Show Comments (37)