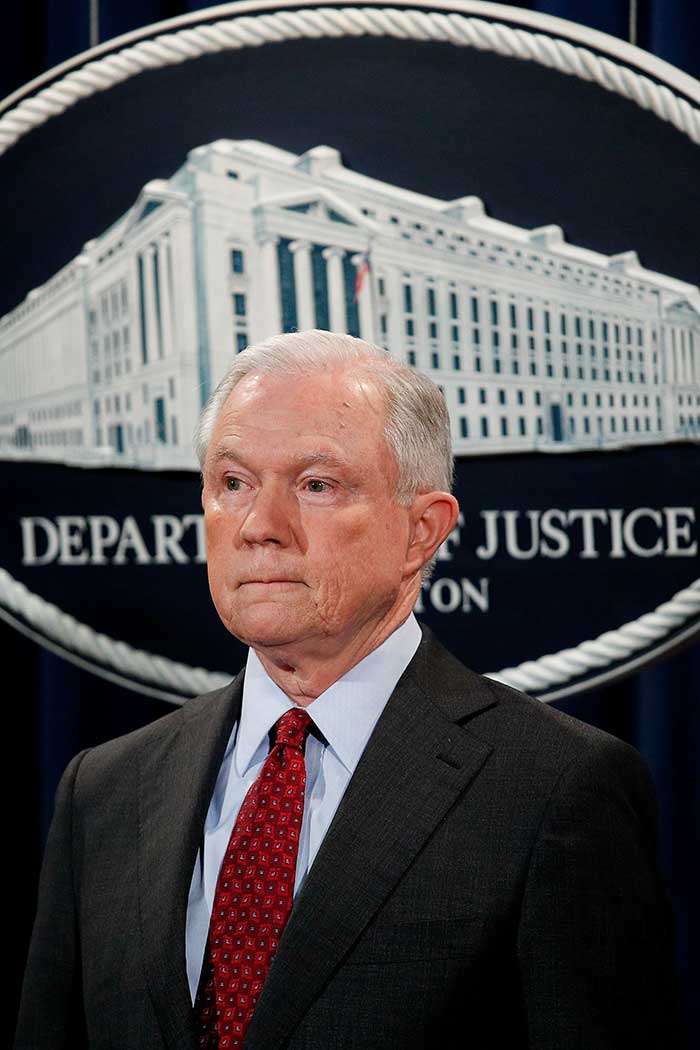

Jeff Sessions Is Taking Law Enforcement Back to the 1980s

On asset forfeiture, prison sentences, and police oversight, Trump's beleaguered attorney general is rolling back decades of progress.

To hear Donald Trump tell it, Attorney General Jeff Sessions—Trump's earliest and most like-minded supporter from the Senate—is "very weak" and "beleaguered," a constant disappointment to the president who promised crowds they would win so much they would get sick of it.

Trump has repeatedly said he is disappointed in Sessions, most recently in an interview with The Wall Street Journal, for Sessions' decision to recuse himself from the ongoing Russia investigation. The denouncements have left Washington wondering if Sessions will be the next major administration official to be ousted in the ongoing weekly reality TV show that is the Trump White House.

For his part, Sessions has said he will stay put unless he's fired. The reasons he would tolerate being publicly berated by the president of the United States on a regular basis are fairly obvious: While the rest of the White House has been floundering, Sessions has been able to steadily impose his will from his perch at the nation's top law enforcement agency.

Although turnover and a federal hiring freeze have left U.S. Attorneys offices understaffed, hampering his directives to ramp up federal drug cases, Sessions has still rolled back Obama-era policies that he's deemed too "soft" on crime, ordered reviews of ongoing consent agreements with troubled police departments, and installed like-minded staffers in key positions. On Friday, Sessions announced that, as part of a crackdown on unauthorized leaks that have plagued the Trump administration, the Justice Department would be reviewing its policies for subpoenaing media organizations. "We respect the important role that the press plays and will give them respect, but it is not unlimited," Sessions said—a warning shot to the press that the Justice Deparment may not shy away from compelling them to testify about their sources.

And unlike Trump's vague populism or the naked careerism of the president's other cabinet appointees, Sessions is driven by a clear ideological vision. His record in the Senate, his actions as attorney general, and his speeches to top law enforcement leaders have articulated a concrete view of crime and punishment in America. That view is rooted in the ideas and tactics that have recently fallen out of favor, even among many of Sessions' Republican colleagues: stiff sentencing policies, the embrace of a Manichean war on drugs and crime that favors police action above police oversight, and the expanded use of controversial tools like civil asset forfeiture. Sessions is taking law enforcement back to the 1980s.

After watching the Obama administration and an increasing number of his own party repudiate that ideology, Sessions is now in a position to rehabilitate it. Perhaps most importantly, because Congress failed to pass any substantive criminal justice reforms during the two- to three-year window when there was real momentum to do so, Sessions has been able to pursue his goals with the laws already on the books. He is exactly where he has always wanted to be.

"In the Senate, you get paid for your words. But in the Department of Justice, every now and then you can actually take action and set priorities and see it actually take effect," Sessions told the Associated Press last week during a trip to El Salvador. "It's kind of a real adjustment. I was a federal prosecutor for 12, 14 years, really. This is coming home to the Department of Justice I so much loved and still do. You can make things happen in the Department of Justice."

Take the issue of civil asset forfeiture, which allows police to seize people's property on the mere suspicion that is connected to criminal activity, like drugs. The practice has become widely criticized by both Republicans and Democrats in recent years, but Sessions has always been a staunch defender of it. In a 2015 Senate Judiciary Committee hearing, after listening to speaker after speaker trot out a parade of horribles about asset forfeiture, Sessions had his turn. Ninety-five percent of asset forfeiture cases, Sessions declared, involve people "who have done nothing in their lives but sell dope."

The quote is classic Sessions and reveals quite a bit about how he sees criminal justice. Civil rights groups and media investigations have uncovered dozens, if not hundreds, of cases of U.S. citizens who had their property—including houses—seized without an accompanying criminal conviction or even charges filed against them. But for Sessions, sticking it to drug dealers is more important than the five percent of people whose civil rights may be violated. You're either on the side of the dopers or the thin blue line.

Last month, Sessions announced he was loosening rules surrounding asset forfeiture. It may be Trump's administration, but we're living in Sessions' world now.

Criminal justice advocacy groups that spent the last year expecting, at best, major legislation to pass Congress or, at worst, a sympathetic administration in the White House now find themselves playing defense. Kanya Bennett, the legislative counsel at the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), says the civil rights organization "is very troubled by what we see as return to the failed war on drugs."

"When he was in the Senate, and certainly in the last Congress, we saw that he was an outlier in the approach to criminal justice reform," Bennett says. "Unfortunately, we see now he can as one man, without the consensus of his party or Congress, advance agenda that he has long prioritized."

Jason Pye, the vice president of legislative affairs for FreedomWorks—an influential conservative advocacy group that joined the bipartisan alliance of organizations pushing criminal justice reform legislation—puts it more succinctly.

"'I Love the '80s' is a great TV show," Pye says, "but it doesn't make for good policy."

Sessions believes long prison sentences deter crime

Sessions' career in law enforcement started as an assistant U.S. attorney in Alabama in the mid-1970s. The Reagan administration appointed him to be a U.S. Attorney in 1981, and his record there shows the preoccupation with the drug war and long sentences that would mark his later political career. A Brennan Center analysis of federal sentencing data during Sessions' tenure showed that 40 percent of his office's convictions were for drugs, about double the rate of other federal prosecutors in Alabama, and those sentences were on average much longer than other offices.

Reagan tapped Sessions to be a federal judge in 1986. However, his nomination was scuttled by well-publicized accusations of racism. He continued to serve as a U.S. Attorney until then-Attorney General Janet Reno asked for his nomination in 1993.

He was elected Alabama attorney in general in 1994. In 1996, Sessions co-sponsored a state bill that would have made second-time drug offenses, including marijuana, punishable by the death penalty.

Alabama voters sent Sessions to the U.S. Senate in 1996, where he became a consistent opponent of efforts to roll back mandatory minimum sentences or reform drug laws. Sessions' views softened somewhat over the years, as did those of many former "tough on crime" Democrats and Republicans, but the idea that stiff sentences deter crime, while "soft" sentences do the opposite, is still central to how Sessions approaches his job.

One of Sessions' first major moves as attorney general was to roll back a 2013 directive by former attorney general Eric Holder that instructed U.S. Attorneys to avoid charges in certain low-level drug cases that would trigger lengthy mandatory minimum sentences. It's prosecutors' duty, Sessions argues, to seek the maximum sentences on the books.

In several speeches and a Washington Post op-ed, Sessions explicitly linked Holder's policy to the national rise in violent crime that began in 2015. "The truth is that while the federal government softened its approach to drug enforcement, drug abuse and violent crime surged," Sessions wrote.

The Justice Department has not released any evidence to back up Sessions' claim. That's because it doesn't exist, says Vanita Gupta, the President of the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights and the former head of the Justice Department's Civil Rights Division under Obama.

"There's no evidence to substantiate that causation," Gupta says. "Jeff Sessions' view of criminal justice policy is out of line with the moves of his own party in states and localities around the country, and it really revives policies that run counter to evidence that exists now."

The notion that Holder's policy caused a national spike in violent crime is absurd on its face. Holder's 2013 directive had a notable but uneven effect on the federal prison population of around 200,000 inmates, but no effect on state prisons and county jails, which incarcerate 86 percent of the 2.2 million Americans behind bars.

"Jeff Sessions' view of criminal justice policy is out of line with the moves of his own party in states and localities around the country, and it really revives policies that run counter to evidence that exists now."

On a more fundamental level, the notion that mass incarceration was a significant factor in driving down crime is contentious at best. Various empirical studies have tried to measure the impact of mass incarceration on the national decline in crime that began in the mid-1990s. Those studies found that the warehousing of millions of Americans had some effect on the dropping crime rate, but estimates of that contribution vary from as high as 27 percent of the overall drop in violent crime to as low as 4 percent. A 2015 Brennan Center study also argued that these studies failed to take into account diminishing returns on incarceration, which may have led the authors to overestimate its impact.

Sessions believes in "broken windows" policing

Closely tied to Sessions' belief in the efficacy of stiff sentencing is his faith in the "broken window" theory of policing—the idea that the aggressive enforcement of low-level "quality of life" crimes—such as public drinking and urination, disorderly conduct, and possession of small amounts of marijuana—will lead to a reduction in more serious felonies. The theory gained prominence in New York City, where it was zealously applied by the NYPD through the 1990s and 2000s. The theory has been hotly debated ever since it was floated in the '80s, with civil rights groups and community activists arguing that it degrades police relations and criminalizes poverty.

In a speech to the National District Attorneys Association in Minneapolis in July, Sessions called broken-windows policing "lawful and proven to work."

Sessions made similar comments in an April interview with a New England radio host: "New York has proven community-based policing, this CompStat plan, the broken windows, where you're actually arresting even people for smaller crimes—those small crimes turn into violence and death and shootings if police aren't out there."

Last year, however, the New York Police Department Inspector General released a report that "found no empirical evidence demonstrating a clear and direct link between an increase in summons and misdemeanor arrest activity and a related drop in felony crime." Indeed, when the NYPD drastically reduced quality-of-life enforcement between 2010 and 2015, crime rates continued to decline.

The ACLU is currently suing Milwaukee, where the police chief is a devoted disciple of broken-windows policing, and he has imported much of the New York City model, including saturation policing that has resulted in hundreds of thousands of police stops of pedestrians and motorists. The ACLU argues the program disproportionately targets minority residents for suspicionless stops and searches.

"We know that excessive policing does not result in increased public safety. It terrorizes communities and often those are black and brown communities," the ACLU's Bennett says. "In the hundreds of thousands of stops that were made [in New York City] , the number that resulted in contraband being recovered were marginal."

Sessions supports civil asset forfeiture

Last month, Sessions announced he was rolling back directives limiting civil asset forfeiture, a controversial practice that allows police to seize property on the mere suspicion that it is involved with criminal activity.

"[W]e hope to issue this week a new directive on asset forfeiture—especially for drug traffickers," Sessions announced. "With care and professionalism, we plan to develop policies to increase forfeitures. No criminal should be allowed to keep the proceeds of their crime. Adoptive forfeitures are appropriate as is sharing with our partners."

Civil asset forfeiture has long been established in common law, but Congress gave the laws real teeth in the mid-80s, allowing federal law enforcement to coordinate with state and local police to seize cash and property suspected of being connected to criminal activity, especially drugs.

The purpose of the laws was to go after drug cartels and other organized crime by cutting off their flow of illicit proceeds. But since the 1980s, the program has exploded, raking in billions of dollars in cash. Over the past several years, a growing bipartisan chorus of advocacy groups and legislators have called on asset forfeiture laws to be reformed, arguing that the lack of safeguards has resulted in police shaking down average citizens for petty amounts of cash, without convicting or even charging them with crimes.

"We know that excessive policing does not result in increased public safety. It terrorizes communities and often those are black and brown communities."

Responding to the chorus of calls for reform, former attorney general Eric Holder issued a directive in 2015 curtailing when federal authorities could "adopt" forfeiture cases from state and local police. Such adoptions account for a relatively small amount of federal forfeiture actions, but they allowed local police to bypass state laws, which were also becoming stricter due to bipartisan reform laws.

Sessions, on the other hand, has been a consistent champion of asset forfeiture. During his tenure on the Senate Judiciary Committee, Sessions opposed restrictions on the practice, saying it was "unthinkable that we would make it harder for the government to take money from a drug dealer than it is for a businessperson to defend themselves in a lawsuit."

As attorney general, Sessions had another perfect opportunity to ramp up the war on drugs and roll back what he saw as the Obama administration's unnecessary skepticism of police.

When Sessions announced he was rescinding Holder's directive, it prompted outcries from both Democrats and Republicans, such as Sen. Rand Paul, who said in a statement that "I oppose the government overstepping its boundaries by assuming a suspect's guilt and seizing their property before they even have their day in court."

The Justice Department introduced new guidelines that it says will curtail abuse of asset forfeiture, but the message to police is clear: You've got a green light to go after property.

Sessions is skeptical of police oversight

Sessions distaste for the Obama administration's approach to policing is perhaps most evident when it comes to federal oversight of state and local police. The Obama administration dramatically ramped up the number of "pattern-and-practice" investigations into unconstitutional policing across the country, at least relative to previous presidential administrations, which rarely exercised the power. Many of these investigation resulted in court-enforced "consent decrees" between the Justice Department and troubled departments that mandated ongoing oversight and policing reforms. For Sessions, this was an all-out attack on the integrity and independence of police—the use of a few bad eggs and anecdotal stories to smear entire police departments as corrupt.

"One of the most dangerous, and rarely discussed, exercises of raw power is the issuance of expansive court decrees," Sessions wrote in the forward to a 2008 report by the Alabama Policy Institute. "Consent decrees have a profound effect on our legal system as they constitute an end run around the democratic process."

Sessions said he hadn't even read the Justice Department Civil Rights Division's scathing reports on unconstitutional policing in Chicago and Ferguson, Missouri. "I have not read those reports, frankly," Sessions told The Huffington Post earlier this year. "We've had summaries of them, and some of it was pretty anecdotal, and not so scientifically based."

It was no surprise when Sessions announced this April that the Justice Department would be reviewing all of the ongoing consent decrees with police departments.

The Justice Department even asked to delay the finalization of a consent decree hammered out between Baltimore and the department in the waning days of the Obama administration, citing "grave concerns" with the details. The agreement was the result of a report by Justice Department's Civil Rights Division finding that the Baltimore Police Department had engaged in a litany of unconstitutional and brutal policing practices.

Baltimore officials balked at the Justice Department's request, and a judge denied it.

Gupta says the Justice Department's authority to monitor and correct constitutional abuses by local police departments—authorized by Congress after the 1991 beating of Rodney King at the hands of L.A.P.D. officers—is a legal obligation and was far from overbearing.

"The retreat on police reform suggests an abdication of responsibility on Jeff Sessions and this Justice Department's part to do that important work," Gupta says. "It's a tool that's been used very judiciously. In a country that has between 16,000 and 17,000 police departments, I think there's 15 consent decrees that the Justice Department is enforcing."

"Nobody is saying the process is easy," Gupta continued. "Yet for the police departments where the Justice Department has had consent decrees, it's been in the aftermath of a pretty serious set of breakdowns that really hurt police department's ability to have the trust of the communities that they serve."

As Radley Balko wrote in The Washington Post recently, Sessions embraces the self-policing of police and federalist tendencies only when they don't clash with his larger priorities. Sessions also recently made federal grants to local and state law enforcement contingent on their cooperation with federal immigration authorities, an overt shot at sanctuary cities defying the Trump administration's crackdown on illegal immigration.

In April, the Justice Department criticized New York City for being "soft on crime" for its immigration stance, outraging city officials, including the NYPD. Sessions quickly backed off that claim. It was, so far, his only major faux pas with the boys in blue, and he enjoys the support of most of the major policing unions and organizations in the country.

Last month, the Fraternal Order of Police, which bills itself as the largest police union in the country with more than 330,000 members, released a statement praising Sessions leadership. While it did not mention Trump's criticism directly, it said it stood "ready to assist and support the Attorney General in the months and years ahead."

For Trump, who made constant overtures to police on the campaign trail, Sessions may be too effective and too popular with his core supporters to replace.

"Sessions is a critical part of the Trump administration—and before there was a Trump administration, Sessions was a critical part of the 'movement' that elected Trump to the presidency," Breitbart scribe and Trumpland amanuensis Matt Boyle wrote last week. "Losing Sessions could endanger the administration and the split the critical coalition that helped Trump to the presidency."

But even if Sessions is politically expendable, he'll probably have to be pried out of his office. There's nowhere else he'd rather be at the moment.

(The Justice Department did not make Sessions available for an interview for this story.)

Show Comments (29)