How Capitalism Saved the Bees

A decade after colony collapse disorder began, pollination entrepreneurs have staved off the beepocalypse.

You've heard the story: Honeybees are disappearing. Beginning in 2006, beekeepers began reporting mysteriously large losses to their honeybee hives over the winter. The bees weren't just dying—they were abandoning their hives altogether. The strange phenomenon, dubbed colony collapse disorder, soon became widespread. Ever since, beekeepers have reported higher-than-normal honeybee deaths, raising concerns about a coming silent spring.

The media swiftly declared disaster. Time called it a "bee-pocalypse"; Quartz went with "beemageddon." By 2013, National Public Radio was declaring "a crisis point for crops" and a Time cover was foretelling "a world without bees." A share of the blame has gone to everything from genetically modified crops, pesticides, and global warming to cellphones and high-voltage electric transmission lines. The Obama administration created a task force to develop a "national strategy" to promote honeybees and other pollinators, calling for $82 million in federal funding to address pollinator health and enhance 7 million acres of land. This year both Cheerios and Patagonia have rolled out save-the-bees campaigns; the latter is circulating a petition calling on the feds to "protect honeybee populations" by imposing stricter regulations on pesticide use.

A threat to honeybees should certainly raise concerns. They pollinate a wide variety of important food crops—about a third of what we eat—and add about $15 billion in annual value to the economy, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. And beekeepers are still reporting above-average bee deaths. In 2016, U.S. beekeepers lost 44 percent of their colonies over the previous year, the second-highest annual loss reported in the past decade.

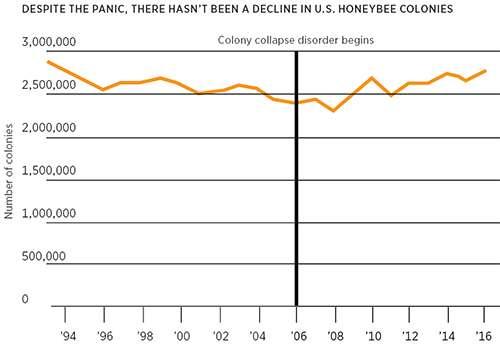

But here's what you might not have heard. Despite the increased mortality rates, there has been no downward trend in the total number of honeybee colonies in the United States over the past 10 years. Indeed, there are more honeybee colonies in the country today than when colony collapse disorder began.

Beekeepers have proven incredibly adept at responding to this challenge. Thanks to a robust market for pollination services, they have addressed the increasing mortality rates by rapidly rebuilding their hives, and they have done so with virtually no economic effects passed on to consumers. It's a remarkable story of adaptation and resilience, and the media has almost entirely ignored it.

The Bee Business

The chief reason commercial beekeeping exists is to help plants have sex. Some crops, such as corn and wheat, can rely on the wind to transfer pollen from stamen to pistil. But others, including a variety of fruits and nuts, need assistance. And since farmers can't always depend solely on bats, birds, and other wild pollinators to get the job done, they turn to honeybees for help with artificial insemination. Unleashed by the thousands, the bees improve the quality and quantity of the farms' yields; in return, the plants provide nectar, which the bees use to produce honey.

Honeybees are essentially livestock. Their owners breed them, rear them, and provide proper nutrition and veterinary care to them. Unlike bumblebees and wasps, honeybees are not native to North America; the primary commercial species, the European honeybee, is thought to have been introduced by English settlers in the 17th century.

Commercial beekeepers are migratory. They truck their hives across the country in tractor trailers on a journey to "follow the bloom," stacking their hives on semis and moving at night while the bees are at rest. Most travel to California in the early spring to pollinate almonds. After that, they take their own routes. Some go to Oregon and Washington for apples, pears, and cherries; others to the apple orchards of New York. Some pollinate fruits and vegetables in Florida in the early spring, followed by blueberries in Maine.

Like any such transit project, accidents happen—as when one beekeeper, Lane Miller, crashed his truck in a canyon near Bozeman, Montana, in 2014. More than 500 hives—about 9 million sleepy, angry bees—spilled onto the roadway. "The bees were so agitated you could barely see the beekeepers or the wreckage itself," said the local fire chief at the time. After 14 hours, hundreds of stings, and a crew of emergency beekeepers, the road finally reopened.

Still, the migration is mostly uneventful. After blooming season, beekeepers shift their focus from pollinating crops to making honey. Many commercial crops that require honeybee pollination, such as almonds and apples, do not provide enough nectar for the bees to produce surplus honey. So in the summer, beekeepers often head to the Midwest, where they essentially pasture the bees, turning their hives loose in fields near sunflower, clover, or wildflowers, which supply large amounts of nectar and allow the bees to make plenty of honey. When summer ends, the beekeepers truck their bees back south to spend the winter in warmer climates.

Some observers claim that this annual migration is contributing to colony collapse. As the food writer Michael Pollan put it in The New York Times in 2007, "the lifestyle of the modern honeybee leaves the insects so stressed out and their immune systems so compromised that, much like livestock on factory farms, they've become vulnerable to whatever new infectious agent happens to come along." But it is precisely this modern-livestock lifestyle and the active markets for pollination services that have allowed non-native honeybees to flourish on our continent. They are the reason honeybee populations have remained steady even in the face of disease and other afflictions.

The Fable of the Bees

Before the 1970s, it was widely believed among academics that the pollination industry's very existence was a problem. In a 1952 paper, the appropriately named economist J.E. Meade argued that honeybee pollination was an "unpaid factor" in apple farming, since orchard owners and beekeepers did not coordinate their production decisions. Both produce what economists call "positive externalities," or spillover benefits for the other, causing inefficiencies. Since "the apple-farmer cannot charge the beekeeper for the bee's food, which the former produces for the latter," Meade believed that certain "subsidies and taxes must be imposed." (Indeed, Washington established a honey price-support program in 1952 with the goal of promoting pollination. The program was briefly eliminated in 1996, but has since been resurrected.)

But then another economist, Steven Cheung, investigated how the honeybee pollination market actually worked. In a 1973 study, he found plenty of contracting between beekeepers and orchard owners to overcome the problem Meade had identified. All he had to do was open the yellow pages of the phone book to find listings for pollination services. "The fable of the bees," as Cheung called it, was blackboard theorizing. Real-life farmers and beekeepers were solving this problem on their own.

Sometimes the farmers paid the beekeepers to pollinate their crops; other times the beekeepers paid the farmers for the right to place hives in their orchards. It all depended on which activity—pollination or honey production—generated more value in that instance. Sometimes the exchange involved both money and honey. Meade, meanwhile, had gotten his central example backward: Apple pollination does not yield much honey, so the beekeeper charges the apple farmer, not the other way around.

The details differ, but markets for pollination services clearly exist and work quite well. Today, commercial beekeeping is a $600–$700 million industry that spans all regions of the country. And now the beekeepers and farmers are working together to overcome another apiary challenge: dead bees.

Adaptation

There have been 23 episodes of major colony losses since the late 1860s. Two of the most recent bee killers are Varroa mites and tracheal mites, two parasites that first appeared in North America in the 1980s. The latter, which attack their hosts' breathing tubes, devastated hives in many states before honeybees began to develop a genetic resistance. The former—tick-like parasites that suck bees' blood—remain a scourge for beekeepers today. Other threats to bee colonies include American foulbrood (which attacks bee larvae), nosema (which invades bees' intestinal tracts), and chalkbrood (which infests bees' guts, causing them to starve).

Beekeepers have developed a variety of strategies to combat these afflictions, including the use of miticides, fungicides, and other treatments. While colony collapse disorder presents new challenges and higher mortality rates, the industry has found ways to adapt.

Rebuilding lost colonies is a routine part of modern beekeeping. The most common method involves splitting a healthy colony into multiple hives—a process that beekeepers call "making increase." The new hives, known as "nucs" or "splits," require a new fertilized queen bee, which can be purchased from a commercial queen breeder. These breeders produce hundreds of thousands of queen bees each year. A new fertilized queen typically costs about $19 and can be shipped to beekeepers overnight. (One breeder's online ad touts its queens as "very prolific, known for their rapid spring buildup, and…extremely gentle.") As an alternative to purchasing queens, beekeepers can produce their own queens by feeding royal jelly to larvae.

Beekeepers regularly split their hives prior to the start of pollination season or later in the summer in anticipation of winter losses. The new hives quickly produce a new brood, which in about six weeks can be strong enough to pollinate crops. Often, beekeepers can replace more bees by splitting hives than they lose over the winter, resulting in no net loss to their colonies.

Another way to rebuild a colony is to purchase "packaged bees" to replace an empty hive. (A 3-pound package typically costs about $90 and includes roughly 12,000 worker bees and a fertilized queen.) A third method is to replace an older queen with a new one. A queen bee is a productive egg-layer for one or two seasons; after that, replacing her will reinvigorate the health of the hive. If the new queen is accepted—as she often is when an experienced beekeeper installs her—the hive can be productive right away.

Replacing lost colonies by splitting hives is surprisingly straightforward and can be accomplished in about 20 minutes. New queens and packaged bees are also inexpensive. If a commercial beekeeper loses 100 of his hives, replacing them would come at a cost—the price of each new queen, plus the time required to split the existing hives—but it is unlikely to spell disaster. And because new hives can be up and running in short order, there is little or no lost time for pollination or honey production. As long as some healthy hives remain that can be used for splitting, beekeepers can quickly and easily rebuild lost colonies.

Colonies Collapse

But there are dead bees and then there are dead bees.

In the fall of 2006, the Pennsylvania beekeeper David Hackenberg went to check on a group of hives he had left in a gravel lot near Tampa. To his surprise, the hives were nearly empty. No adult bees, no dead bees—just a lonely queen and a few young stragglers in each one. The others had simply vanished. Altogether, Hackenberg lost more than two-thirds of his 3,000 hives. Within a few weeks, other beekeepers began reporting similar problems. By February 2007, the strange affliction was given a name: colony collapse disorder.

Beekeepers have always lost a portion of their hives each year to parasites, infections, pests, and other diseases, but this was different. The collapse was widespread and far more deadly. That winter, beekeepers across the country lost 32 percent of their colonies, more than twice their average winter mortality rates. Similar losses were reported in Europe, India, and Brazil.

The problem captured the world's attention in part because it was mysterious. Hackenberg and the other beekeepers did not find evidence of mites, robber bees, wax moths, or any of the other common pests or ailments that often kill the insects. The hives were still chock full of honey, pollen, eggs, and larvae. But the worker bees were gone.

Ten years later, scientists still debate the causes of colony collapse disorder. Researchers have been unable to pinpoint an exact culprit, and most now believe a variety of factors are at play, including infections, pathogens, and malnutrition.

Environmental groups such as Greenpeace and the Natural Resource Defense Council often blame neonicotinoids—a class of "systemic" pesticides that are soaked onto seeds and absorbed throughout the entire plant as it grows—and call for regulations restricting their use. The European Union implemented a partial ban on neonicotinoids in 2013 due to their possible impact on bees, but the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has yet to take similar action in the United States.

Earlier this year, in fact, the agency determined that four common neonicotinoid pesticides "do not pose significant risks to bee colonies," though that finding is disputed by environmental groups. And recent evidence suggests that the E.U.'s ban has done more harm than good, by encouraging farmers to use other, more lethal pesticides.

A Buzzing Economy

To see how effective beekeepers' strategies have been in the face of colony collapse, examine the data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture's annual beekeeper surveys. In 2016, there were 2.78 million honeybee colonies in the United States—16 percent more than when the disorder hit in 2006. In fact, there are more honeybee colonies in the country today than in nearly 25 years. Honey production also shows no pattern of decline. Last year, U.S. beekeepers churned out 161 million pounds of honey, slightly more than when colony collapse began.

What about the broader impacts of rebuilding lost colonies? In a new working paper, the Montana State University economist Randal Rucker, the North Carolina State University economist Walter Thurman, and the Oregon State University entomologist Michael Burgett come to a surprising conclusion: The disorder has had almost no discernible effect on the economy. Even as beekeepers have had to repeatedly rebuild their lost hives, the overall costs to them, and to consumers, have been minimal.

Thank the perseverance of beekeepers and the resilience of pollination markets. To rebuild after winter losses, beekeepers must purchase more packaged bees and queen bees from specialized breeders. Yet even these bees' prices have been largely unaffected by the increase in demand brought about by colony collapse disorder. Using annual data collected from advertisements in the American Bee Journal, a beekeeping magazine, the researchers find no measurable increase in the prices of these bees after controlling for pre-existing trends. One reason is that supply is extremely elastic: Commercial queen breeders are able to rear large numbers of queen bees quickly, often in less than a month, to meet increased demand.

Colony collapse did have a significant effect on one price. The pollination fees that beekeepers charge almond producers have more than doubled since the early 2000s. The researchers attribute a portion of this increase—roughly $60 per colony—to the onset of colony collapse. But even this impact has a bright side for beekeepers: In some cases, the increase in almond pollination fees has more than offset the costs they have incurred rebuilding their lost colonies.

While the increase in those pollination fees may have increased costs for almond producers, the effect on consumers has been negligible. Rucker, Thurman, and Burgett find that colony collapse disorder increased the price of a one-pound can of almonds by 1 percent—a mere 8 cents for a can of Smokehouse Almonds. And because almond production is one of the agricultural sectors most reliant on honeybees for pollination, the researchers consider that to be an upper-bound estimate of the impact on the prices of fruits and vegetables.

A Cautionary Tale—for Journalists

If a beepocalypse was really upon us, colony numbers and honey production would be declining, the costs associated with rebuilding lost hives would be rising sharply, and the prices of the crops most reliant on honeybees would be rapidly increasing. Yet none of these appear to be the case.

Modern commercial beekeeping practices create real stresses on beekeepers and honeybees alike. But we shouldn't exaggerate their plight or overlook how successfully they've adapted to a changing world. In the words of Hannah Nordhaus, author of the 2011 book The Beekeeper's Lament, the scare stories surrounding colony collapse disorder "should serve as a cautionary tale to environmental journalists eager to write the next blockbuster story of environmental decline."

Indeed, our obsession with honeybees may have distracted us from other, more important environmental concerns. Wild pollinators such as bumblebees, butterflies, and other native insects really do appear to be in decline, thanks to habitat loss and agricultural development. After all, unlike honeybees, there is no commercially minded beekeeper to look after them.

Earlier this year, one of those wild pollinators, the rusty patched bumblebee, was listed as an endangered species in the United States. Monarch butterflies appear to be getting more scarce as well.

But while the media declares disaster and the federal government attempts to create a "national pollination strategy," commercial beekeepers have quietly rebuilt their honeybee colonies to even greater numbers than before colony collapse disorder began a decade ago. Instead of standing idly by while their colonies vanish in the face of disease or pests, these migratory beekeepers, with their trucks full of bees and honey, continue to ply the roads between various crops to provide the pollination services our modern agricultural economy demands—busy as, well, you know.

CORRECTION 7/21/17: An earlier version of this story mistakenly said that an 8-cent increase in the price of a pound of almonds amounted to a tenth of a percent. It's actually a 1 percent increase.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "How Capitalism Saved the Bees."

Show Comments (61)