Americans Should Impeach Presidents More Often

We don't do it nearly enough.

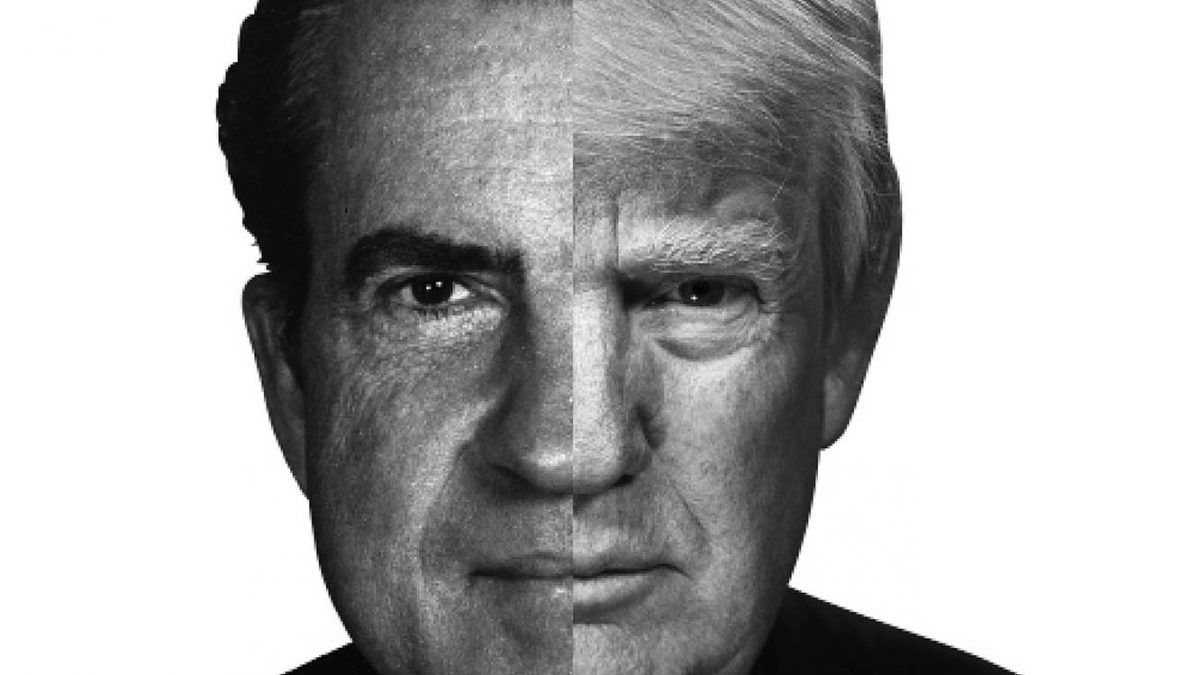

Impeachment talk in the nation's capital rose from a murmur to a dull roar in mid-May, thanks to a week jam-packed with Nixonesque "White House horrors." On Tuesday, May 9, President Donald Trump summarily fired FBI director James Comey; on Thursday, Trump admitted the FBI investigation into "this Russia thing"—attempts to answer questions about his campaign's links with Moscow—was a key reason for the firing; Friday found Trump warning Comey he'd "better hope that there are no 'tapes' of our conversations"; and the following Tuesday The New York Times reported the existence of a Comey memo on Trump's efforts to get the FBI director to "let this go." Along the way, Trump may have "jeopardized a critical source of intelligence on the Islamic State" while bragging to Russian diplomats about his "great intel," according to The Washington Post.

Still, the Beltway discussion of impeachment remained couched in euphemism, as if there was something vaguely profane and disreputable about the very idea. "The elephant in the room," an NPR story observed, "is the big 'I' word—impeachment"; "the 'I' word that I think we should use right now is 'investigation,'" House Judiciary Committee member Rep. Eric Swalwell (D–Calif.) told CNN's Wolf Blitzer.

We don't call it "the v-word" when the president signals he might veto a bill. Yet somehow, when it comes to the constitutional procedure for ejecting an unfit president, journalists and Congress members—grown-ups, ostensibly—are reduced to the political equivalent of "h-e-double-hockey-sticks."

What's really obscene is America's record on presidential impeachments. We've made only three serious attempts in our entire constitutional history: Andrew Johnson in 1868, Bill Clinton in 1998—both of whom were impeached but escaped removal—and Richard Nixon, who quit in 1974 before the House could vote on the issue. Given how many bastards and clowns we've been saddled with over the years, shouldn't we manage the feat more than once a century?

A 'National Inquest Into the Conduct of Public Men' Impeachments "will seldom fail to agitate the passions of the whole community, and to divide it into parties," Alexander Hamilton predicted in the Federalist. That's how it played out during our last national debate on the subject, during the Monica Lewinsky imbroglio of the late '90s.

The specter of Bill Clinton's removal from office for perjury and obstruction of justice drove legal academia to new heights of creativity. Scads of concerned law professors strained to come up with a definition of "high Crimes and Misdemeanors" narrow enough to let Bill slide. In a letter delivered to Congress as the impeachment debate began, over 430 of them warned that unless the House of Representatives wanted to "dangerously weaken the office of the presidency for the foreseeable future" (heaven forfend), the standard had to be "grossly heinous criminality or grossly derelict misuse of official power."

Some of the academy's leading lights, not previously known for devotion to original intent, proved themselves stricter than the strict constructionists and a good deal more original than the originalists. The impeachment remedy was so narrow, Cass Sunstein insisted, that if the president were to up and "murder someone simply because he does not like him," it would make for a "hard case." Quite so, echoed con-law superprof Laurence Tribe: An impeachable offense had to be "a grievous abuse of official power," something that "severely threaten[s] the system of government."

Just killing someone for sport might not count—after all, Tribe pointed out, when Vice President Aaron Burr left a gutshot Alexander Hamilton dying in Weehawken after their July 1804 duel, he got to serve the remaining months of his term without getting impeached. Still, Tribe generously allowed, in the modern era "there may well be room to argue" that a murdering president could be removed without grave damage to the Constitution.

In the unlikely event that Donald Trump orders one of his private bodyguards to whack Alec Baldwin, it's a relief to know that Laurence Tribe will entertain the argument for impeachment. But does constitutional fidelity really require us to put up with anything short of "grievous," "heinous," existential threats to the body politic?

The Framers borrowed the mechanism from British practice, and there it wasn't nearly so narrow. The first time the phrase appeared, apparently, was in the 1386 impeachment of the Earl of Suffolk, charged with misuse of public funds and negligence in "improvement of the realm." The Nixon-era House Judiciary Committee staff report Constitutional Grounds for Presidential Impeachment described the English precedents as including "misapplication of funds, abuse of official power, neglect of duty, encroachment on Parliament's prerogatives, [and] corruption and betrayal of trust."

As Hamilton explained in the Federalist, "the true spirit of the institution" was "a method of national inquest into the conduct of public men," the sort of inquiry that could "never be tied down by such strict rules…as in common cases serve to limit the discretion of courts."

If the standard is "unacceptable risk of injury to the republic," Trump's behavior just may be impeachable.

Among those testifying beside Sunstein and Tribe in 1998 was Northwestern's John O. McGinnis, a genuine originalist, who argued that the Constitution's impeachment provisions should be viewed in terms of the problem they were designed to address: "how to end the tenure of an officer whose conduct has seriously undermined his fitness for continued service and thus poses an unacceptable risk of injury to the republic."

Contra Tribe, who'd compared impeachment to "capital punishment," McGinnis pointed out that the constitutional penalties for unfitness—removal and possible disqualification from future office holding—went "just far enough," and no further than necessary, "to remove the threat posed." In light of the structure and purpose of impeachment, he argued, "high Crimes and Misdemeanors" should be understood, in modern lay language, roughly as "objective misconduct that seriously undermines the official's fitness for office…measured by the risks, both practical and symbolic, that the officer poses to the republic."

Today, even the president's political enemies tend to set the bar far higher. Donald Trump has acted in a way that is "strategically incoherent," "incompetent," and "reckless," Democratic leader Rep. Nancy Pelosi said in February, but "that is not grounds for impeachment."

But incoherence, incompetence, and recklessness are evidence of unfitness, and when we're talking about the nation's most powerful office they can be as damaging as actual malice. It would be a pretty lousy constitutional architecture that only provided the means for ejecting the president if he's a crook or a vegetable, but left us to muddle through anything in between.

Luckily, Pelosi is wrong: There is no constitutional barrier to impeaching a president who demonstrates gross incompetence or behavior that makes reasonable people worry about his proximity to nuclear weapons.

Impeachable Ineptitude When Barack Obama was president, Trump once asked, "Are you allowed to impeach a president for gross incompetence?" Earlier this year, Daily Show viewers found that tweet funny enough to merit the "Greatest Trump Tweet of All Time" award. Still, it's a valid question.

The conventional wisdom says no, largely on the basis of a snippet of legislative history from the Constitutional Convention. As James Madison's notes recount, when Virginia's George Mason moved to add "maladministration" to the Constitution's impeachable offenses, Madison objected: "So vague a term will be equivalent to a tenure during pleasure of the Senate." Mason yielded, substituting "other high crimes & misdemeanors."

But the Convention debates were held in secret, and Madison's notes weren't published until half a century later. Furthermore, the language Mason substituted was understood from British practice to incorporate "maladministration." Nor did Madison himself believe mismanagement and incompetence to be clearly off-limits, having described impeachment as the necessary remedy for "the incapacity, negligence, or perfidy of the chief Magistrate."

Thus far, the Trump administration has been a rolling Fyre Festival of negligence and maladministration, from holding a nuclear strategy session with Japan's prime minister in the crowded dining room of a golf resort to having the former head of Breitbart News draft immigration orders without the assistance of competent lawyers. Near as I can tell, James Comey's verbal incontinence had a bigger impact on the 2016 election than Russian espionage, but liberals hold out hope for a "smoking gun" of collusion that's unlikely ever to emerge. Meanwhile, the Trump administration was apparently clueless that firing the FBI director in the midst of the Russia investigation would be a big deal, and Trump himself was unaware that admitting he did it in hopes of quashing the inquiry was a stupid move.

As the Comey story emerged, pundits and lawbloggers debated whether, on the known facts, the president's behavior would support a federal felony charge for obstruction of justice. But that's the wrong standard. As the Nixon Impeachment Inquiry staff report pointed out: "the purpose of impeachment is not personal punishment. Its purpose is primarily to maintain constitutional government." Even if, to borrow a phrase from Comey, "no reasonable prosecutor" would bring a charge of obstruction on these facts, the House is free to look at the president's entire course of conduct and decide whether it reveals unfitness justifying impeachment.

A Rhetorical Question? The Nixon report identified three categories of misconduct held to be impeachable offenses in American constitutional history: "exceeding the constitutional bounds" of the office's powers, using the office for "personal gain," and, most important here, "behaving in a manner grossly incompatible with the proper function and purpose of the office."

It would be pretty lousy constitutional architecture that only provided the means for ejecting the president if he's a crook or a vegetable, but left us to muddle through anything in between.

When Trump does something to spark cries of "this is not normal," the behavior in question often involves his Twitter feed. The first calls to impeach Trump over a tweet came up in March, when the president charged, apparently without evidence, that Obama had his "wires tapped" in Trump Tower.

The tweet was an "abuse of power," "harmful to democracy," and potentially impeachable, Harvard Law's Noah Feldman proclaimed: "He's threatening somebody with the possibility of prosecution." Laurence Tribe, of all people, agreed. Murder may have been a hard case, but slander? Easy call. Trump's charge qualified "as an impeachable offense whether via tweet or not."

I confess it wasn't the utterly speculative threat to Barack Obama that disturbed me about Trump's Twitter feed that day in March; it was that a mere two hours after lobbing that grenade, Trump turned to razzing Arnold Schwarzenegger for his "pathetic" ratings as host of Celebrity Apprentice. The Watergate tapes exposed much more than a simple abuse of power. They revealed a fragile, petty, paranoid personality of the sort you'd be loath to entrust with the vast authority of the presidency. And Nixon didn't imagine that the whole world would be listening. Trump's Twitter feed is like having the Nixon tapes running in real time over social media, with the president desperate for an even bigger audience.

As it happens, there's precedent for impeaching a president for bizarre behavior and "conduct unbecoming" in his public communications. The impeachment of Andrew Johnson gets a bad rap, in part because most of the charges against him really were bogus. The bulk of the articles of impeachment rested on Johnson's violation of the Tenure of Office Act, a measure of dubious constitutionality that barred the president from removing Cabinet officers without Senate approval.

But the 10th article of impeachment against Johnson, based on different grounds, has gotten less coverage. It charged the president with "a high misdemeanor in office" based on a series of "intemperate, inflammatory, and scandalous harangues" against Congress. In a series of speeches in the summer of 1866, Johnson had accused Congress of, among other things, "undertak[ing] to poison the minds of the American people" and having "substantially planned" a race riot in New Orleans that July. Such remarks, according to Article X, were "peculiarly indecent and unbecoming in the Chief Magistrate" and brought his office "into contempt, ridicule and disgrace."

'Peculiar Indecencies' From a 21st century vantage point, the idea of impeaching the president for insulting Congress seems odd, to say the least. But as Jeffrey Tulis explained in his seminal work The Rhetorical Presidency, "Johnson's popular rhetoric violated virtually all of the nineteenth-century norms" surrounding presidential oratory. Johnson stood "as the stark exception to general practice in that century, so demagogic in his appeals to the people" that he resembled "a parody of popular leadership." The charge, approved by the House but not voted on in the Senate, was controversial at the time, but besides skepticism about whether it reached the level of a high misdemeanor, "the only other argument offered by congressmen in Johnson's defense was that he was not drunk when giving the speeches."

It's impressive that Trump—a teetotaler—manages to pull off his "peculiar indecencies" while stone cold sober. Since his election, Trump has used Twitter to rail against restaurant reviews, Saturday Night Live skits, "so-called judges," and America's nuclear-armed rivals. The month before his inauguration, apropos of nothing, Trump announced via the social network that the U.S. "must greatly strengthen and expand its nuclear capability," following up the next day on Morning Joe with "we will outmatch them at every pass and outlast them all."

As Charles Fried, Reagan's solicitor general, observed, "there are no lines for him…no notion of, this is inappropriate, this is indecent, this is unpresidential." If the standard is "unacceptable risk of injury to the republic," such behavior just may be impeachable. An impeachment on those grounds wouldn't just remove a bad president from office; it would set a precedent that might keep future leaders in line.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Americans Should Impeach Presidents More Often.."

Show Comments (141)