American Communism

A million hippie kids shaped modern America by trying to escape it.

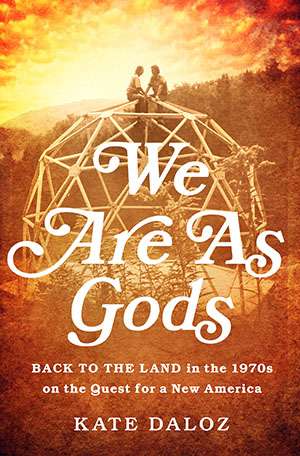

We Are As Gods: Back to the Land in the 1970s on the Quest for a New America, by Kate Daloz, PublicAffairs, 355 pages, $26.99

In 1971, a young man named Bernie Sanders visited Myrtle Hill Farm, a rural Vermont commune for disaffected white middle-class kids. Its residents' back-to-the-land lifestyle was meant to free them from a culture that had come, in the midst of war and racial unrest, to seem "an unstoppable torrent of death and destruction, all for no reason."

Myrtle Hill had an all-are-welcome policy—for three days. Then the core owners would decide by consensus whether you were cool to hang around. Sanders' tendency to just sit around talking politics and avoid actual physical labor got him the boot.

That's just one of the stories in Kate Daloz's We Are As Gods, a loving but honest history of hippie communes in Vermont in the 1970s. Daloz has the journalist's gift for getting people to explain themselves, the historian's ability to explain the context in which they made their choices, and the novelist's power for revealing character through action, plot, and the perfectly chosen detail. While she focuses on a small group of communal and quasi-communal rural homesteads within a few miles of each other in Vermont—one of which housed her parents, Judy and Larry—Daloz explains that her characters represented a large and unprecedented cultural and demographic shift.

The decision to build a saner, purer way of life away from urban civilization and private property was "being made almost simultaneously by thousands of other young people all across the country at the same moment for almost the same reason," she writes. No other point in American history, Daloz says, saw so much deurbanization, with as many as a million young Americans going back to the land. Almost all of them, she notes, were from middle-class white backgrounds; most were well-educated, with no fear that they couldn't make their way quite well in normal society. This gave them a safety net "that made such radical choices possible."

Their motive was liberty—the freedom to control their own environment, education, technology, diet, productivity. (To the significant number of draft dodgers and teen runaways involved, their very liberty to live free of violence was at stake.) But though this is not Daloz's central point, her fine-grained narrative shows that being free of the technologies and wealth thrown off by the national and international division of labor carried with it its own tyranny.

Many of these young communalists believed their world was doomed, whether through nuclear war, fascistic repression, or ecological megadeath. Learning how to live off the land, then, was about survival itself, not just ideological self-satisfaction. One of this book's main characters was driven to rural Vermont by the realization that if the industrial civilization that was all he knew broke down, he'd "just fucking die. You'd just stand there and die." He felt it his duty to thrive off only the soil, water, and animals on his property with techniques that didn't require energy or fuel from the outside world.

But as everyone in We Are As Gods soon learned, a small group of human beings pitted against nature were at a far greater disadvantage than they dreamed. Despite the valorization of Stewart Brand's Whole Earth Catalog and its ethos of learning to master the tools and technologies of self-sufficient living, far too many people attracted to the movement knew—as Robert Houriet, one of the original chroniclers of the scene, put it—all about the Tarot but nothing about how to fix a pump.

Myrtle Hill outlasted the vast majority of similar communes that arose at the same time. Its rise and fall, from 1970 to the mid-'80s, is the spine of the book's narrative. (Daloz notes that groups with a unified and specific religious or sociological goal tended to last longer than ones with the pure, groovy "let's hang out and be free together" attitude of Myrtle Hill.)

One of the original Myrtle Hill couples, Fletcher and Nancy, had already lived at what might be the original weird arty hippie commune of the era, Colorado's Drop City, whose open-door policy quickly led it to druggy, decadent decay while helping to popularize the idea of jury-rigged geodesic domes as good hippie living. Fletcher and Nancy hoped that non-rat-race life in rural Vermont would give them plenty of time to pursue their interests in filmmaking and painting. It didn't work out that way.

The lives of the Myrtle Hill gang become intertwined with a smaller communal grouping of two couples in a nearby farmhouse dubbed Entropy Acres. The latter's troubles were many and varied. To start with, since one of the couples held the actual deed to the property, the other couple often felt powerless. The couples also dueled over the propriety of eating meat. Fully committed to a "no modern conveniences" ethic, they tried to farm for money using no machine power. The task was incredibly hard and remarkably unlucrative. Their early attempt to pump organic carrots into the national supermarket system grossed $3,000 for 18,000 pounds of carrots; each individual vegetable had been touched by human hands at least four times and their cultivation worked five adults all day every day for months.

When the Entropy Acres couples tried to re-enter the cash-for-labor economy by seeking jobs as county school bus drivers, they became poster children for the often tense relationship with the townies, who rejected them because it was rumored (correctly) that they grew a little pot on their homestead.

While most of the story takes place in Vermont, a few of her characters understandably didn't want to suffer through Northeast winters without sufficient warm shelter, so they hit the road to survey, and thus help Daloz's readers survey, the burgeoning communal scene across the country.

In one fascinating chapter, we see another example of a commune rubbing against its noncommunal neighbors the wrong way. In a California commune called Morningstar, landowner Lou Gottlieb, formerly a popular folksinger with the Limeliters, declared that "shitting in the garden…is a spiritual act, as well as a constitutional right." He tried to create a legal workaround by signing over legal ownership of the land to "God," but the plan failed. His gang of neighbor-aggravating hippies were condemned as public enemies by Gov. Ronald Reagan and most of the makeshift structures were bulldozed by the authorities.

Daloz's reporting displays the full range of communal experience. There was free love, and sometimes there was jealousy. There was self-sufficiency, and sometimes there was no way to keep warm. There were canvas tents for shelter, and sometimes there were icicles hanging from the inner ceiling that could take your eye out. (And if you were sheltering your cow in such a tent, and the snow settled too heavy, there were a collapsed tent and a dead cow.) There was tobogganing through the snow with your loving comrades, drunk on your homemade dandelion wine; and then there was spreading meningitis and staph to each other. There was the joy of building a self-contained toilet system, and then the relief of putting out a fire in that toilet without burning down your whole dome.

There were children being raised by a village, and there were parents getting tense and angry when another adult tried to discipline their kid. There was talk of total equality, and there was the reality that the women were cooking, cleaning, and minding the children while men got high around the fire and made big plans. There was the glorious freedom of disconnection from the corporate death culture, and there was the endless drudgery required to eat and be anything close to comfortable.

The final blow that shattered the Myrtle Hill experiment came courtesy of the expanded drug war in the Reagan '80s. Jed, one of the early Myrtle Hill residents, took to growing lots of marijuana. He protected that pot with lots of guns and fences on what was supposed to be group land, and became consumed by a raging paranoia that destroyed any sense of communal togetherness, fun, or eventually even safety. (Though Daloz does not seem to have interviewed Jed himself, one of her central characters, Myrtle Hill's mainstay matriarch Lorraine, also briefly dabbled in pot growing on the property. Lorraine said her motive was needing cash to pay taxes.)

When Jed got busted, the Myrtle Hill crew needed a lot of expensive legal help and political pull to avoid having their land seized by the feds. Craig, Myrtle Hill's original source of cash, was proud of the "communal land trust" legal structure in which the full-timers (each of whom had been chosen by consensus) took turns making the monthly mortgage payments. Eventually, a legal entity controlled by all of them owned the land.

But even before Jed's bust, some of the folks who had put tons of sweat equity into improving the land and the houses on it realized they were trapped unless they were willing to abandon the homes they'd built. A normal American landowner could make money by selling her property if she wanted to leave. That wasn't possible under Myrtle Hill's communal structure, which sucked for those who felt terrorized by the erratic Jed.

After the trauma of his arrest, the communards managed to agree to split ownership into a more standard personal model for the 20 acres surrounding each individual home. Three of the group continued to own the remaining unoccupied land communally for a few years. Then their "spouses called a reality check" on paying taxes on land they didn't use, and they sold it.

Daloz cares deeply for her characters—remember, two of them are her parents—and she is ultimately kind in her judgments about their successes and failures, their impact on themselves and America. But she is an honest enough reporter that not every reader will share her perspective. You may be charmed by a hippie romance that begins when the young lady sees that the young man keeps peanut butter smeared on his hat brim in case he gets hungry, or you may not. But Daloz's caring, detailed understanding of who these people are, why they did what they did, and the lessons they learned is skilled enough that it's hard not to become interested in seeing whether everything turns out well for them.

From this reader's perspective, it doesn't. The communalists' physical and emotional experiences seem harder than they needed to be. (Not that most of them didn't have a lot of edenic memories as well.) Lives far less ambitious and adventurous than the ones these colonists chose can also go wrong, so perhaps they ought not be uniquely faulted for their fecklessness. But it can't be denied that this is a story of people who were very mistaken in their assumptions about how their choices would work out for them.

For one thing, they often didn't realize that pre-industrial rural life was never so much self-sufficient as village-sufficient: It was idiotic to try to be your own grower, miller, baker, and blacksmith if it wasn't absolutely necessary. They also grossly underestimated how much richer, healthier, and more comfortable the divisions of labor found in industrial civilization make us.

Yet her characters did not completely eschew the market economy; because these communes were voluntary experiments with room for lots of trial and error, they were able to make some lasting contributions to American culture beyond an extended lesson in things not to do. Craig, one of Myrtle Hill's founders, recognized the need to get their groovy foodstuffs organized, sold, and transported. So he began the Loaves and Fishes trucking company, which helped forge a national network among food co-ops for those who wanted homemade cheeses and granolas and exotic spices such as cumin that had previously been very hard to find in the U.S.

Such hot modern brands as Celestial Seasonings, Burt's Bees, Tom's of Maine, Stonyfield Yogurt, and Cascadian Farms Organic all arose from the setting Daloz chronicles. As she notes in her conclusion, "every last leaf and crumb of today's $39 billion organic food industry owes its existence" to the 1970s hippie commune scene. America's diet would be far less varied and interesting without them.

Meanwhile, as Daloz notes, "every YouTube DIY tutorial, user review, and open-source code owes something to the Whole Earth Catalog," the periodical that energized the movement and spawned the epigram ("We are as gods and might as well get good at it") from which the title of Daloz's book is taken.

In her brief but entertaining survey of earlier waves of voluntary rural communism, Daloz quotes Louisa May Alcott, who grew up on a commune called Fruitlands. Though she lived a century before Myrtle Hill came into being, Alcott could have been summarizing Daloz's own spirit of clear-eyed admiration tinged with admonition when she noted that "to live for one's principles, at all costs, is a dangerous speculation; and the failure of an ideal, no matter how humane and noble, is harder for the world to forgive and forget than bank robbery or the grand swindles of corrupt politicians." Daloz helps us forgive, but not forget.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "American Communism."

Show Comments (249)