Why Presidential Candidates From Both Parties Are Wrong About Community Banks

Plenty of Americans prefer the convenience of banking somewhere large.

Here's a rare presidential campaign issue that Ted Cruz, Jeb Bush, Marco Rubio, Carly Fiorina, Bernie Sanders, and Hillary Clinton all are on the same side of: they claim to prefer cute little "community banks" instead of Wall Street behemoths. And, as can sometimes be the case in those unusual instances when there's a bipartisan consensus on an issue, the politicians are wrong.

The topic came up over the weekend in the Democratic debate. Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont promised to break up the big Wall Street banks and instead "support community banks and credit unions. That's the future of banking in America."

Strangely enough, the socialist senator's position had been foreshadowed a few days before by some of the top Republican candidates. Said the former governor of Florida, Jeb Bush: "Imagine America without its community banks. Well, that's what's happening because of Dodd-Frank. That's my worry. My worry is that the real economy has been hurt by the vast overreach of the Obama administration.""

Bush's fellow Floridian, Marco Rubio, concurred. "The big banks, they have an army of lawyers, they have an army of compliance officers. They can deal with all these things. The small banks, like Governor Bush was saying, they can't deal with all these regulations," Senator Rubio said. "This is an outrage. We need to repeal Dodd-Frank as soon as possible."

Sen. Cruz, too, echoed the community bank talking point. "The big banks get bigger and bigger and bigger under Dodd-Frank and community banks are going out of business. And, by the way, the consequence of that is small businesses can't get business loans," Cruz said.

Carly Fiorina also weighed in. "What do we have with Dodd-Frank? The classic of crony capitalism. The big have gotten bigger, 1,590 community banks have gone out of business," she said.

Hillary Clinton, the Democrat, addressed the issue recently while campaigning in New Hampshire. "We have to separate out the big banks from the community banks," she said. "I am open to looking at how we help community banks." She advised the community bankers to "come in with their own package" of proposed reforms, "not in concert with the big banks."

You'd need to look through a magnifying glass into the viewfinder of an electron microscope to detect differences between Messrs. Sanders and Cruz, or between Ms. Fiorina and Mrs. Clinton, on this one. They all basically tout the community banks as somehow more sympathetic and worthy of government lenience than the big "Wall Street" firms.

I'm for repealing Dodd-Frank yesterday, but blaming the financial regulation law that President Obama signed on July 21, 2010, for the failure of community banks is nonsensical. More banks failed in 2009, the year before Dodd-Frank passed, than in 2011, the year after it passed. In 2010 more banks failed before the law passed than afterward. And the number of bank failures has been declining as Dodd-Frank implementation and enforcement has ramped up. It's almost enough to make you think the bank failures weren't the result of the law but of the economic downturn.

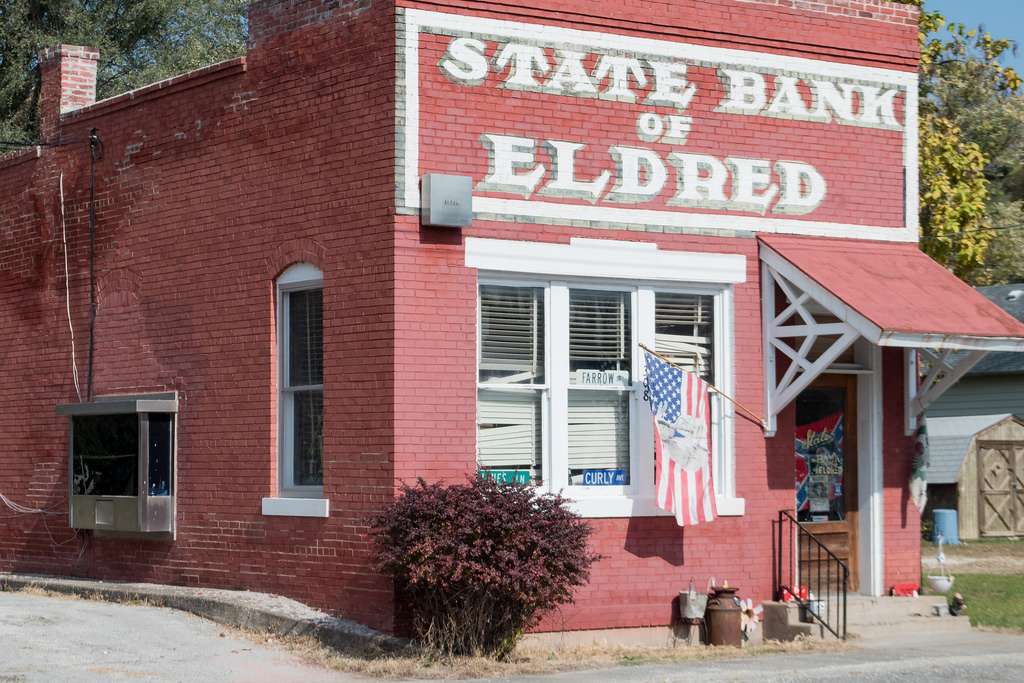

The decline of community banking long preceded Dodd-Frank. A December 2012 report from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. called it "a multi-decade trend" that reduced the number of federally insured banks to 7,357 in 2011 from 17,901 in 1984, and the share of U.S. banking assets held by community banks to 14 percent from 38 percent over the same period.

Bank failures are a part of the reason; small, local banks tend to be highly exposed to commercial real estate loans in one concentrated area and can have a hard time weathering a regional economic slump. But consolidation also happens via mergers and acquisitions. The owners of a community bank make money when their little bank is purchased by a larger regional bank. And the big regional banks get bigger by buying up smaller players, applying economies of scale. The FDIC also blames the relatively poor performance of community banks on low interest rates set by the Federal Reserve.

If customers prefer a personal touch, nothing is stopping them from moving their money to a smaller operator, or starting their own small bank to compete. But plenty of Americans prefer the convenience of banking somewhere large enough to operate a slick website and mobile app and to maintain automatic teller machines, or even branches, not just in their home town but also at their vacation destination or the city where their children are in college.

The presidential candidates seem to understand this at the level of their own behavior. According to personal financial disclosure documents, Hillary Clinton banks at JP Morgan, Jeb Bush at SunTrust, Ted Cruz at Bank of America, JP Morgan, and Capital One, Marco Rubio at Citibank and TD Americatrade. Carly Fiorina's money is invested at Goldman Sachs. Even Senator Sanders banks not at some mom-and-pop operation but at a subsidiary of a large regional bank.

The presidential candidates aren't on the campaign trail talking about the need to break up Lowe's and Home Depot and bring back local neighborhood independent hardware stores. They aren't out there talking about the need to break up Staples and OfficeMax and bring back local independent office supply stores. They aren't talking about the need to get rid of CVS or Target drug stores and replace them with local independent neighborhood pharmacists. So what's with the obsession over small banks?

A cynic—or maybe even Sen. Sanders—might suspect that money has something to do with it. The same personal financial disclosure form that shows Fiorina investing with Goldman Sachs also shows that the Independent Community Bankers of America, a trade association, paid her $48,000 for a speech on March 3, 2015, in Orlando, Fla. Federal Election Commission records show that the Independent Community Bankers of America Political Action Committee donated $2,500 to Ted Cruz's Senate campaign in August 2012 and another $1,000, which was later returned, in November 2012. Hillary Clinton's Senate campaign received $1,000 from this same community bankers' political action committee in 2000 and another $1,000 in 2006. Community bankers are just another special interest group, complete with their own campaign contributions and highly paid revolving-door lobbyists.

But that analysis is probably a little too neat. There's something else at work here, a kind of nostalgia and sentimentalism about the past combined with wishful thinking—hubris, really—about the government's power to turn back the clock. The Republicans and Democrats are both happy to use the big banks as political punching bags. A little humility would go a long way here. Maybe the politicians should just let customers and bankers decide the composition of the banking market rather than trying to push in the direction of small banks against large ones.

Show Comments (26)