U.S. Taxpayers Are Funding Police Brutality in Brazil

With U.S.-supplied weapons and training, Brazil’s militarized police fuel a cycle of violence that claims thousands of lives each year while destabilizing the region.

On November 7, the Military Police of São Paulo (PMESP) shot and killed four-year-old Ryan da Silva in Santos, a port city outside of São Paulo. The authorities' excuse, as is often the case in Latin American police killings, was that the police perceived a threat. There is no evidence for this claim.

The killing is endemic to the extreme brutality of Brazilian police, one of the most violent and militarized police services in the world. The United States government has helped create this crisis.

In 2023, the Military Police in Brazil recorded having killed 6,296 people (approximately 17 people per day)—eight times the U.S. police lethality rate—yet evidence points to the actual number being much higher. The overwhelming majority of the victims are black, poor, young, male, uneducated, and living in the urban peripheries. Prominent politicians, activists, and scholars in Brazil have referred to this as a "genocide."

As Brazil's militarized policing has continued to expand, so have the gangs' control and influence. Brazilian authorities seized 72.3 tons of cocaine in 2023. Gangs have bought, threatened, and manipulated elections, politicians, and members of the judiciary. Last year, 3,238 people were found to be enslaved by gangs, and gangs have control of entire cities and the prison system. They have major stakes in real estate, mining, petroleum, casinos, and cryptocurrency, valued at billions of dollars. There have been hundreds of cases of police working directly for organized crime, including as contract killers, creating an incentive against eliminating criminality.

This does not come from disarmed policing. Brazil currently has over 800,000 police officers—half of which are in the Military Police—coming from 1,595 security agencies. The Military Police has access to high-caliber weapons, aircraft equipped with weapons, armored cars, and even tanks. Every day, Brazilian police carry out dozens of special operations against drug cartels, using SWAT teams and night vision equipment while following a rigid structure, not dissimilar from raids one might see from the U.S. military in war zones.

Most of the weapons used by Brazilian police come from U.S. suppliers. This includes the Colt M4 carbine, the Mossberg 590A1 shotgun, the Browning M2 machine gun, various sniper rifles, night vision systems, armored vehicles, and helicopters—all American-made.

The gangs also use American weapons, sold to intermediaries without strong checks by U.S. manufacturers (and very often provided by police officers involved with gangs and militias). These U.S. weapons were once legally sold by the U.S. government to the Brazilian police.

Brazil's "shock" policing strategy has failed. Where these strategies are employed, there are now more gangs than ever, including in Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo, and the state of Bahia. Meanwhile, the Brazilian Amazon, which has the highest rates of police per capita, has been overflowing with gangs, who use the largely ungoverned space to traffic drugs, weapons, and people—all the way to the U.S. southern border. The Brazilian Amazon's homicide rate has shot through the roof, more than double that of Iraq's warzones despite nearly a quarter of all violent deaths being at the hands of police. In some cities in Brazil, that share exceeds 50 percent, meaning the police are responsible for most violent deaths.

Brazil's policing affects the United States. The Primeiro Comando da Capital (PCC) and the Comando Vermelho (CV), the country's two largest gangs, now have reported networks in the United States, including in Miami and Boston. (Some Brazilian nationals affiliated with local gangs have already been deported from the U.S.) A few weeks ago, in broad daylight, the PCC assassinated a businessman at São Paulo's international airport, firing 29 shots at the airport terminal door and injuring three other people.

The security crisis creates further regional instability and migration. Since 2019, the number of migrants from Brazil in the United States has quadrupled. There are now over 2 million Brazilian nationals residing in the U.S.—at least 195,000 without legal status, according to the Migration Policy Institute. A significant share of them cite security issues as a main factor in them leaving their home.

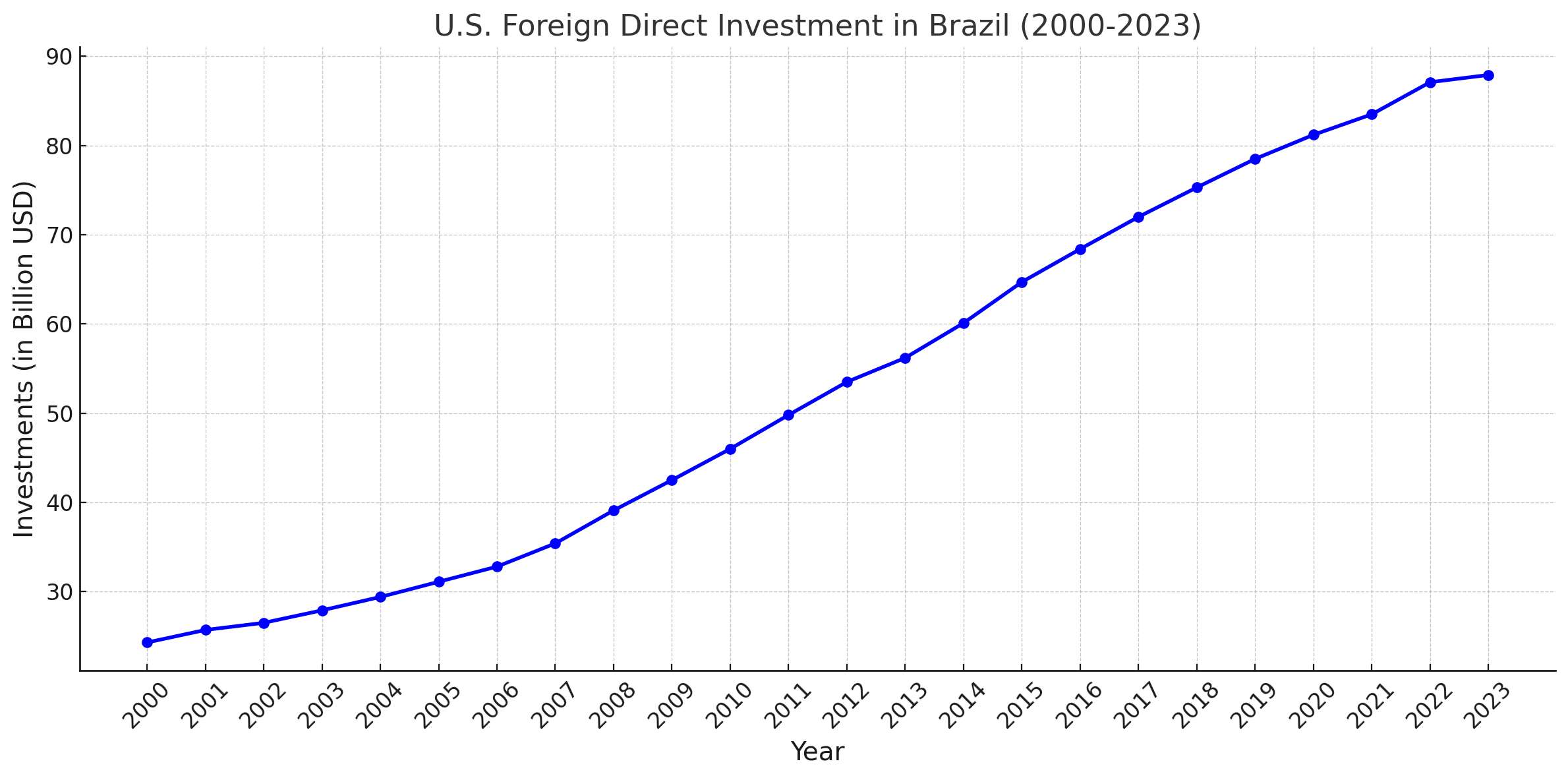

The violence also affects U.S. trade with Brazil. Currently, the U.S. is Brazil's second-largest trading partner, after China, according to the World Bank. The U.S. is responsible for about 20 percent of all foreign direct investment into Brazil, which, rising each year, is projected to reach $100 billion by 2030. In 2023, U.S. exports to Brazil were valued at over $38 billion.

Beyond its advanced weapons, the U.S. shapes Brazil's hyper-militarized police culture where the motto, "a good criminal is a dead criminal," is flaunted by most police institutions. Under this philosophy, everyone living in the poor peripheries is considered a criminal, given that they reside in "criminal areas." Physical and psychological torture is still taught in Brazil's police academies. There are hundreds of cases of victims being abused by police, including judges, prosecutors, activists, and journalists. Adriano Magalhães da Nóbrega, a former officer in the Special Police Operations Battalion (BOPE), ran one of Latin America's largest contract-killing, drug trafficking, and gambling networks. He notably used the training he gained at BOPE to torture and brutally kill his targets, some of whom were prominent figures.

This is, in part, a result of the training given to them by the United States.

The U.S. State Department, along with the FBI, has provided various training programs and exercises with the Brazilian military police. One of these programs, promoted by both the Trump and Biden administrations, the "Rapid Response to Active Shooters Course," began in 2019 and is meant to "quickly and effectively respond to attacks involving shooters in public spaces." In the overwhelming majority of police killings in Brazil, officers and their precincts insist that they "were met with gunfire," despite many prominent cases showing that the police shot first.

One of the most egregious cases was the summary execution of 12 civilians by nine Military Police officers (PMs) in the neighborhood of Cabula in Salvador da Bahia, one of the country's largest cities. The PMs, during the judicial process, sent death threats to the victims' families, while the governor referred to the act of "football players hitting the ball into the net." Judges and prosecutors, intimidated by the governor and the police, acquitted the officers, while two prosecutors resigned from the case. This kind of cartoonish rendition of justice through extreme state violence, with political support, is a common occurrence in Brazil.

In some of these cases involving "Rapid Response to Active Shooters," PMs used excessive force, discharging randomly in public spaces, with extremely high civilian death rates. The police lethality rate in Brazil has increased at a significantly faster rate than the homicide and violent crime rates, demonstrating that police lethality has been used disproportionately as a deterrent and response against criminal actors and factions. Police lethality, as one officer in the PMESP recounted, "is the state's way of containing criminality, and providing order and justice."

The joint State-FBI training program is run with all Brazilian law enforcement agencies, including the Military Police, in the country's largest states, the most important being São Paulo, where homicide rates are skyrocketing. The FBI, along with the LAPD and the Chicago Police, have also provided riot and protest control training to the Brazilian police, as protests in Brazil are often met with excessive police brutality, including using tear gas and rubber bullets.

Today's Military Police is a remnant of Brazil's military dictatorship, which was also supported by the U.S. State Department, the FBI, and the CIA during the Cold War. Then, the Military Police was used as a political hammer to bludgeon political opponents, union leaders, and any Communist threats. The U.S. government produced local anti-Communist propaganda while funding and arming the state's death squads. U.S. agencies also trained the Military Police to use some of the most extreme tactics still in use today.

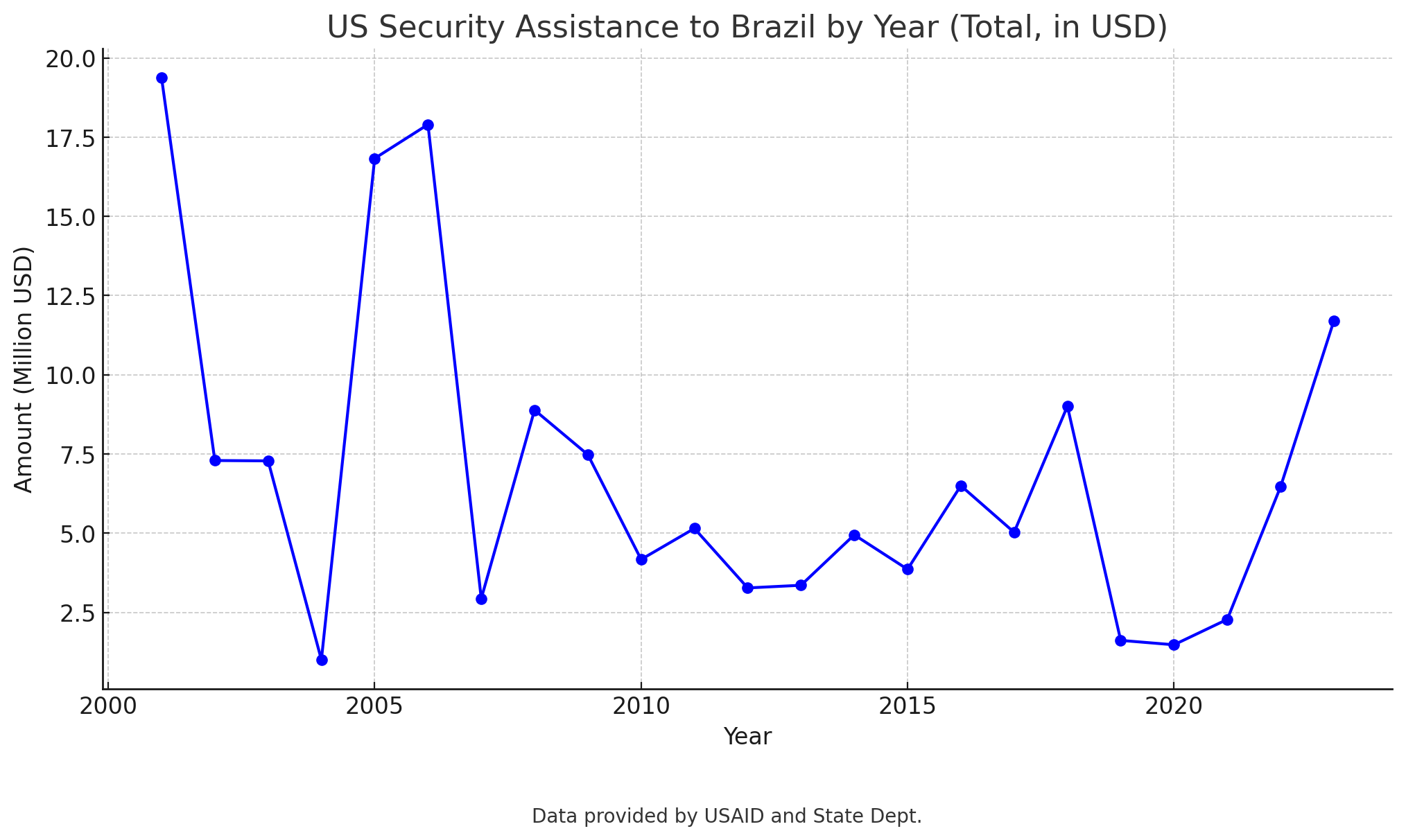

A democratic Brazil has done little to reform the Military Police's ruthless and repressive practices, with continued U.S. backing. Last year, the U.S. State Department gave $11.7 million to the Brazilian security state, returning to Bush-era numbers despite little progress made. The overwhelming majority of U.S. security assistance went to Brazilian law enforcement, financially rewarding ineffective policing.

The enduring legacy of unchecked militarized policing and U.S. state involvement—funded by our taxpayer money—continues to fuel a cycle of violence that affects both Brazilian society and broader regional stability.

Show Comments (21)