Will SCOTUS Take on New York's Latest Eminent Domain Scam?

Two brothers are asking the Supreme Court to stop their town from using eminent domain to steal their land for an empty field.

What happens when the government lies about why it's seizing your land? That's the central issue in Brinkmann v. Town of Southold, a case being considered by the Supreme Court.

Property rights are inextricably connected to economic security and community. Property gives people a space to raise families, build communities, start a business, practice their faith, and debate their views. This is especially true for disfavored groups most vulnerable to the wishes of a hostile majority. But as with all constitutional rights, property rights exist only to the extent our courts protect them.

The Fifth Amendment was one of the ways our nation's founders sought to protect property rights. Its Takings Clause restricts the government's power to seize land through eminent domain, requiring that any taking be "for public use." But what happens when the government lies about why it's taking land, feigns a public use, and a judge blindly accepts the government's reasons?

Consider Bruce's Beach, a black resort in Manhattan Beach, California, in the early 20th century. Mere decades after emancipation, Willa Bruce and her husband moved to Los Angeles to earn a living by operating a small seaside business. They purchased a parcel in 1912 and opened a retreat where guests could buy soda and lunches, rent bathing suits, and swim.

Within a week of opening, white neighbors and local officials grew agitated and harassed the guests. Despite the challenges, Bruce's Beach flourished, expanding from a modest portable cottage to a two-story brick building to accommodate the growing number of guests. Inspired by its success, other black families also began purchasing property in the area.

As opposition increased, Bruce stood firm. "I own this land," she said. "And I am going to keep it."

Out of options, Manhattan Beach officials resorted to eminent domain to force the Bruces out of business. To justify the seizure, the city fabricated a "public use," claiming the land was needed for "public park purposes."

Public parks are a valid public use, but this park was a mere pretext. In the three decades that followed, no park appeared on the land, but the Bruces—and their business—were gone.

Examples of pretextual takings abound. In the 1950s, officials targeted a thriving black community of homes and businesses called Belmar Triangle in Santa Monica, California. A series of bad faith takings devastated the area and upended families under the guise of "urban renewal." But in the end, the city never built much more than a parking lot for a new event space.

In the 1980s, Burlington, Massachusetts, targeted affordable housing by using eminent domain for a sham park until the state's high court stepped in. Branford, Connecticut, tried something similar in 2010. That same decade, officials used eminent domain to go after a mosque in Wayne, New Jersey. After exhausting other options to stop construction, the township decided it needed the land for "open space."

Abuses like these flip the Takings Clause on its head. Instead of protecting property owners, the provision legitimizes bad-faith land grabs.

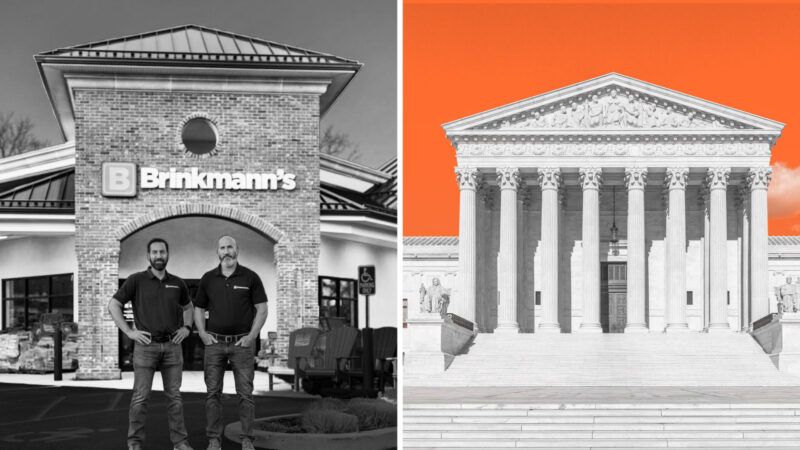

Now, the Supreme Court has a chance to curb the abuse with a petition from brothers Ben and Hank Brinkmann. Their legal battle started in 2017 when they tried to build a hardware store on their own land in Southold, Long Island.

Hostile to the project, town officials tried myriad ways to stifle the brothers' plans. The mayor personally interfered with the land sale, and city officials demanded tens of thousands of dollars for an impact study. After the Brinkmanns complied, officials enacted a dubious building permit moratorium, affecting only a small stretch of road centered on the Brinkmanns' property. Still, the brothers did not give up.

When all else failed, Southold took the Brinkmanns' land using eminent domain. What "public use" did the town conjure up as a pretext for the bad faith taking? Officials claimed they needed the land for a "passive use park." That's an empty field. In other words, the public use was a sham.

Earlier this year, the 2nd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals rubber-stamped the town's bad faith taking, with the majority concluding that "when the taking is for a public purpose, courts do not inquire into alleged pretexts and motives." All three judges deciding the appeal agreed that the Brinkmanns had alleged a pretextual taking. Two judges nonetheless held for the majority that the Fifth Amendment offers no protection.

Dissenting judge Steven Menashi felt differently: "In my view, the Constitution contains no Fake Park Exception to the public use requirement of the Takings Clause."

As with the case in Manhattan Beach and so many others, telling the truth would have derailed Southold's scheme to stop the Brinkmanns. Instead, the town resorted to lying about the "public use" to feign compliance with the Fifth Amendment.

Brinkmann v. Town of Southold is now at the Supreme Court's door. If the government can hide behind false claims of public use, property rights—and the Fifth Amendment—become meaningless.

This case is about more than one family's fight to open a hardware store. It's about holding the government accountable for its lies and ensuring that constitutional protections mean something. When the government lies, courts must protect our rights.

CORRECTION: The original version of this article erroneously listed a co-author. That author has been removed.

Show Comments (35)