The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

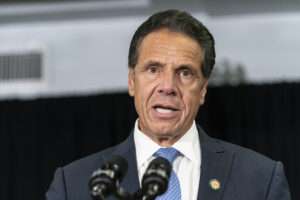

The Supreme Court Was Right to Consider Andrew Cuomo's Unconstitutional Motives in NRA v. Vullo - and the same Principle Applies to Trump and Other Presidents

Chief executives' illicit motives can render their subordinates' actions unconstitutional. There is good reason for courts to enforce that rule.

In its recent decision in NRA v. Vullo, the Supreme Court unanimously ruled against the Superintendent of New York's Department of Financial Services in a case where that agency undertook various enforcement actions against financial institutions pressuring them to stop doing business with the NRA, because of that group's advocacy of gun rights. While these actions were seemingly neutral, evidence indicated that the motive behind them was an attempt to suppress the NRA's political speech.

Co-blogger Josh Blackman does not object to this result, but criticizes Justice Sonia Sotomayor's opinion for the Court for relying, in part, on tweets and other statements by then-New York Governor Andrew Cuomo. Josh complains that it's wrong to rely on Cuomo's statements because "he wasn't even a party" to the case, and fears this part of the opinion is "laying the groundwork for some future Trump litigation, where the chief executive's social media posts can be used to taint the action taken by some cabinet member…. it is almost a given that people would allege that President Trump and his administration will engage in some sort of retaliatory or coercive actions against protected speech."

As Josh notes, Trump's tweets and other statements promising a "Muslim ban" were central elements of the case against his travel ban policy, eventually upheld by the Supreme Court in Trump v. Hawaii (2018). I think the Court got that decision badly wrong. Significantly, however, Chief Justice John Roberts' majority opinion did not hold that statements like Trump's were irrelevant, merely that they would not get much weight in the context of immigration policy where the Court concluded (wrongly, in my view) that the executive should get special deference. Thus, statements indicating illicit intent could still potentially be decisive in other types of cases.

The Court was right to consider Cuomo's statements. And it should do the same in potential similar future cases involving Trump or other presidents.

Longstanding Supreme Court precedent holds - for good reason - that facially neutral policies can be unconstitutional if evidence indicates they were adopted for purposes of engaging in discrimination prohibited the Constitution, such as discrimination on the basis of race, religion, or - as in NRA v. Vullo - protected political speech. If such facially neutral policies were immune from challenge, the government could target almost any group for discrimination by focusing on some seemingly neutral characteristic that is correlated with group membership. Instead of explicitly targeting blacks, they could target people who live in majority-black neighborhoods. Instead of openly targeting Muslims, they could (as Trump did) target migrants from various Muslim-majority nations. And so on.

Such tactics were extensively used by advocates of Jim Crow segregation, when courts started striking down explicit segregation laws. More recently, educational institutions have used them as a tool for engaging in racial preferences banned by Supreme Court rulings.

Why consider a governor's or president's statements in cases challenging policies enacted by subordinate officials? The obvious answer is that the former often influence the latter. As Justice Sotomayor notes, Governor Cuomo was "Vullo's boss." Absent his advocacy and support, it is likely she would not have targeted the NRA so aggressively. This is even more clear in the case of Trump's travel ban, a policy which almost certainly would never have been enacted absent his "Muslim ban" campaign promises.

The case for focusing on presidential motives is even more compelling if - like many conservatives - you endorse the "unitary executive" theory of presidential power, under which the president is entitled to near-total control of other executive branch officials. In that framework, subordinates have even more incentive to try to implement the "boss's" directives than in Andrew Cuomo's New York. Officials who refuse to do the boss's bidding aren't likely to be around for long.

The case for scrutinizing presidents' unconstitutional motives is often even stronger than with state governors. In many states, the executive branch is less unitary than in the federal government. For example, New York, like many other state governments, has a separately elected attorney general who is independent of the governor. This played a major role in Andrew Cuomo's eventual downfall. In late 2021, he was forced to resign in large part because of an investigation into accusations of sexual harassment conducted by the New York AG's office. Although AG Letitia James is a Democrat, her independence enabled her office to do the investigation, and Cuomo could not prevent it. The president exercises far more control over the federal Department of Justice, and other parts of the federal executive branch.

In the case of both state and federal officials, the government can still successfully defend a challenged policy if it can prove they would have enacted it even in spite of the chief executive's illicit motives. Vullo has advanced that argument in the NRA case. But Supreme Court precedent rightly shifts the burden of proof to the government in a case where evidence of unconstitutional discriminatory motivation is found.

Back in 2018, during the travel ban litigation, Josh Blackman argued courts can afford to ignore presidents' unconstitutional motives because "I don't know that we'll ever have a president again like Trump, who says such awful, awful things on a daily basis." I was skeptical of such optimism at the time. And I think that skepticism has been vindicated by later events.

Obviously, Trump himself may well be elected again in 2024. And he has already promised to use the power of the federal government to punish his critics. If he does indeed return to power and subordinate officials take actions that appear to implement that promise, courts can and should consider Trump's statements when assessing their legality. Meanwhile, other Republican politicians have increasingly imitated Trump's behavior and policies. Even if he loses again and disappears from the political scene, this problem is unlikely to fully go away.

As NRA v. Vullo shows, left-wing officials also sometimes engage in such behavior. The Democrats may not be as far-gone as the Republicans. But they, too, aren't above using facially neutral policies to cloak unconstitutional motives, including in cases where the latter are evident from various public statements. Particularly in an age of severe polarization, where many on both sides are eager to use the power of government to target their enemies, such behavior is unlikely to go away anytime soon. Judicial review cannot completely prevent such abuses of power. But by paying due attention to illicit unconstitutional motives, it can help curb them substantially.

Show Comments (41)