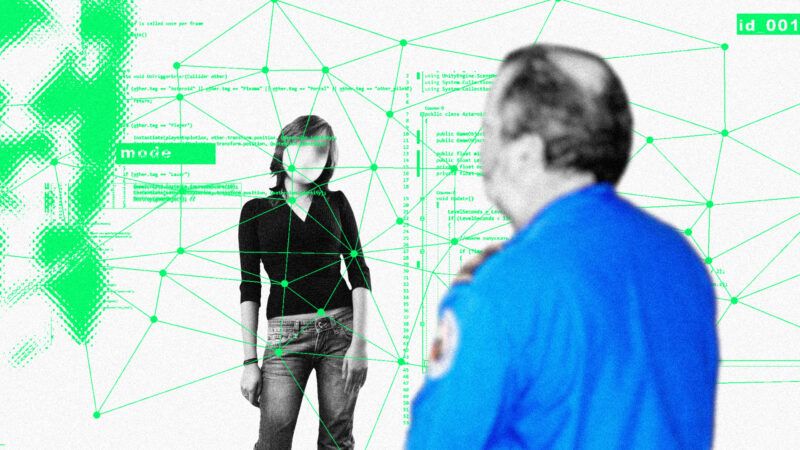

Facial Recognition Comes to a TSA Checkpoint Near You

The government is refining its ability to track your movements with little discussion.

Facial recognition technology has come a long way in recent years, spurred in equal parts by convenience and the priorities of government snoops. Now, if you plan to go a long way via air travel, you can expect to be required to stare into a camera as a computer algorithm scans your features to make sure you're no imposter. The TSA is trying out facial recognition technology at airports as a means of ensuring that travelers are who they claim to be and speeding security lines. It's, maybe, an improvement for impatient travelers, but even more so for the never-satisfied security state.

"The Transportation Security Administration (TSA) at Denver International Airport (DEN) has deployed the next generation of Credential Authentication Technology (CAT) to verify the identity of travelers," the TSA announced last November. "First generation CAT units are designed to scan a traveler's photo identification, confirm the traveler's identity as well as their flight details. The new CAT units, referred to as CAT-2, have the same capabilities, but are also equipped with a camera that captures a real-time photo of the traveler."

The rollout began earlier, with the TSA exploring biometric technologies and then testing the use of facial recognition scanners at airports including LAX. By December 2022, The Washington Post's Geoffrey Fowler noted "the Transportation Security Administration has been quietly testing controversial facial recognition technology for passenger screening at 16 major domestic airports."

Theoretically, travelers can opt out in favor of regular ID checks. But anybody who flies much knows how well things often go when you stand on your rights with the TSA—it's a great way to end up in a back room. Just weeks after writing up the rollout, Fowler told PBS: "since my column came out, readers said they followed that, went up to the podium and got pushback" when they objected to the facial scan.

Among the reasons for objecting to facial recognition scans, reliability is often mentioned.

"Federal government algorithms from 2019 found people with Black or Asian ancestry could be up to 100 times less accurately identified than white men," Fowler pointed out to PBS.

But reliability can be improved as shortcomings are addressed. Just a few years ago, facial recognition often faltered when people masked their faces, such as (to little apparent public-health benefit) during the pandemic. "Even the best of the 89 commercial facial recognition algorithms tested had error rates between 5% and 50% in matching digitally applied face masks with photos of the same person without a mask," the U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) found in 2020.

In new tests just months later, failure rates plunged as algorithms refocused on details of the eyes and nose that aren't covered by face masks. There's little reason to believe that algorithms can't be refined to distinguish people's identity through differences in facial features and skin color.

That said, highly reliable facial recognition only amplifies a lot of other concerns about the surveillance state. Improving Big Brother's competence just sticks us with a more robust Big Brother.

"Facial recognition is a dangerous and invasive surveillance technology that lacks federal safeguards and can too easily be expanded," the Electronic Privacy Information Center's Jeramie Scott objects. "TSA should end its facial recognition program as a step towards reeling back-in the use of facial recognition by the federal government. We must not sit idly by while the infrastructure for mass face surveillance is created."

"Identity-based domestic security programs condition our mobility to freely assemble, associate, speak, and exchange ideas upon the government's permission to do so," adds the Identity Project, which supports the right to travel without document requirements. "Demands on citizens to 'show their ID' have spread from airports to all major forms of long distance public transport."

Fundamentally, even if we take the TSA and other agencies at their word that they want to use facial recognition to identify travelers as seamlessly and accurately as possible, they still intend to identify travelers. The whole project is based on the premise that nobody should be able to anonymously go from place to place. But it wasn't so long ago that, so long as you paid your fare, you could largely travel where you pleased with minimal need to disclose your name.

"Airline travel in the early 1960s was still fairly carefree: If you had a ticket, you could board a plane," the Los Angeles Times observed in 2014.

"As a general rule, until 1941, U.S. citizens were not required to have a passport for travel abroad," reports the National Archives.

The assumption that you should have to prove your identity at all is quite a leap, before we get to discussions about technology, reliability, and records retention. There's probably little short-term chance of reviving the days of anonymous travel, but some lawmakers are raising civil libertarian concerns about the TSA's rush to embrace facial recognition.

"Countries like China and Russia use facial recognition technology to track their citizens," Rep. Jim Jordan (R–Ohio) objected in January. "Do you trust Joe Biden's TSA to use it as well?"

Members of the president's own party also oppose the scheme.

"Increasing biometric surveillance of Americans by the government represents a risk to civil liberties and privacy rights," Senators Ed Markey (D–Mass.), Jeff Merkley (D–Ore), Cory Booker (D–NJ), Elizabeth Warren (D–Mass.), and Bernie Sanders (I–Vt.) wrote last week to TSA Administrator David Pekoske. "Currently if a U.S. traveler shows up to one of the 16 airports testing this technology, they will be met with a facial identification scanner before they can proceed to their flight. Thousands of people daily are encountering a decision to travel or safeguard their privacy- a decision that threatens our democracy."

Incidentally, even if you think anonymous travel is best left in the past, it's not obvious what peril facial recognition is supposed to defeat. A 2021 U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) report revealed that its own earlier facial recognition test bagged few phonies out of tens of millions of scanned faces (23 million in fiscal year 2020 alone).

"Since the program's inception, in 2018, CBP officers at U.S. airports have successfully intercepted seven impostors who were denied admission to the United States and identified 285 imposters on arrival in the land pedestrian environment," the report boasted.

Facial recognition is an increasingly effective technology. But in government hands it's more effective at threatening our privacy and liberty than at offering any real benefit.

Show Comments (15)