The Volokh Conspiracy

Mostly law professors | Sometimes contrarian | Often libertarian | Always independent

Andrew Koppelman Responds to Critics of His Book on Libertarianism [Updated]

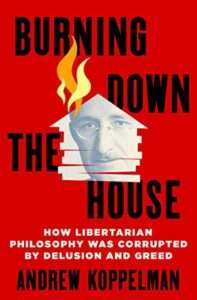

The response is part of the Balkinization blog symposium on his book " Burning Down the House: How Libertarian Philosophy Was Corrupted by Delusion and Greed," in which I was among the participants.

Andrew Koppelman has posted a response to participants in the Balkinization symposium on his recent book Burning Down the House: How Libertarian Philosophy Was Corrupted by Delusion and Greed. I myself was one of the participants (see my contribution here), as were co-blogger Jonathan Adler, Richard Epstein, Christina Mulligan, James Hackney, and others. I thought that Adler and Mulligan developed particularly compelling critiques of key aspects of the book.

Overall, I think Koppelman's response was not especially successful in rebutting the criticisms. But readers will have to judge that for themselves. In fairness, some of the wide-ranging issues raised cannot easily be addressed in a short essay! Here, I offer a brief rejoinder to the part of Koppelman's response addressing my own contribution:

Libertarians are typically drawn to the hypothesis that a nongovernmental solution is always better. It is an hypothesis worth testing, and I say that libertarians have made and continue to make important contributions by insisting upon it (pp. 52-53). Sometimes it is correct. Sometimes it is a disastrous mistake.

Ilya Somin, my old friend and sometime collaborator, falls into that trap. He acknowledges my dissection of the classic libertarian writers, Hayek, Rothbard, Nozick, and Rand, but laments my "neglect of more recent and more sophisticated thinkers…." At 237 pages, the book is necessarily compressed. I wrote it because there existed no short introduction to libertarianism for the general reader that was not written by enthusiasts. The "missed opportunity" Somin describes would have been a different book than I was attempting….

I will say that contemporary libertarians, including Somin, make the same mistakes as their predecessors whom I do describe, preeminently exaggerated trust in unregulated markets and exaggerated distrust of government. Somin is particularly troubled by my "neglect of modern libertarian critiques of democratic government, particularly those focused on voter ignorance and bias." Some modern libertarians, prominently including Somin himself, have argued that this fact is a reason to reject legislation in favor of "private-sector solutions to public goods problems and externalities." I acknowledge the possibility of such solutions…., but I say that "whether this is so in any particular case cannot be resolved without attention to the local evidence…"

The real gap between me and Somin is what I say next: "More fundamentally, the networks of mutual trust that facilitate such cooperation don't develop in nations where government is distrusted. Across prosperous democratic nations, and over time, trust in government and interpersonal trust are tightly correlated." Somin is committed to a picture in which government cannot be trusted to do anything right: given the effect on policy of voter ignorance and bias, "the quality of those policies is likely to be greatly reduced." For reasons I elaborate in the book, that picture is not only destructive to cooperation in markets; it is at some remove from reality. Despite voter ignorance and bias, Congress did manage to enact protections against death in the workplace and foul air, protections that the market was never going to supply, and which the Supreme Court has lately been gutting in the name of liberty.

I agree that "nongovernmental solutions" are not always better than government. However, the points I made about political ignorance as a shortcoming of government relative to foot voting amount to a systematic relative advantage of the private sector that should create a presumption against state control. The problem isn't limited to one or a few specific areas of government policy. The same goes for the points I raised about property rights.

That presumption becomes stronger when we add in a range of other issues raised by the modern libertarian literature on government, markets, and public goods that Koppelman largely overlooks in his book. At the very least, as noted in my contribution to the symposium, these issues pose a formidable challenge to thinkers - including Koppelman himself - who acknowledge many of the important advantages of the private sector, but believe large-scale government intervention can still be justified so long as it is carefully calibrated to address harm caused by market failures, while avoiding creating great new harm of its own. Political ignorance and related issues raised by libertarian scholars (and others) undercut the plausibility of claims that such careful calibration is even remotely possible. It doesn't necessarily follow that we should abjure all government regulation. But it does follow that its scope must be severely limited. Koppelman may have responses to these concerns. But developing them effectively requires grappling with modern libertarian scholarship on these topics.

The issue of trust is one I cannot do justice to here. I will only note that the extent to which trust matters to important social outcomes is highly contested by experts in the field. I summarize some of the literature in chapter 6 of my recent book Free to Move, where I criticize arguments that immigration must be restricted in order to preserve trust. Moreover, it could be that government will be more trustworthy if its powers are strictly limited, and therefore easier for "rationally ignorant" voters to monitor effectively. The immense size and scope of modern government makes political ignorance and resulting demagoguery and abuses of power far more dangerous than they would be otherwise. I discuss those dynamics in more detail in Democracy and Political Ignorance: Why Smaller Goverment is Smarter, and in this more recent article.

Finally, workplace safety was improving (largely due to increased societal wealth) for decades before the development of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration and other modern regulatory regimes. The establishment of OSHA in 1970 does not seem to have increased the pace of change. And, as libertarians often point out, workers should be allowed to decide for themselves whether they wish to accept increased risk in exchange for increased pay or benefits. The Clean Air Act is a much stronger case for Koppelman's thesis. But, as Jonathan Adler points out in his contribution to the symposium, it is also something of an anomaly.

Much more can be said. But, for now, I will stop here. Despite our many disagreements, Koppelman has performed a valuable service by highlighting some key areas of disagreement between libertarians and their critics, especially those on the political left. I hope and expect we will debate these issues further, in the future.

UPDATE: Koppelman responds to this post here:

Somin does not dispute my claim that sometimes, large regulatory programs are justified. But, he says, the characteristic failures of democratic governance "amount to a systematic relative advantage of the private sector that should create a presumption against state control. The problem isn't limited to one or a few specific areas of government policy." This is not, however, the sort of question that is appropriately addressed with presumptions. As I say in the book, "whether this is so in any particular case cannot be resolved without attention to the local evidence." (69) Presumptions are not a substitute for such evidence….

Asymmetries of information create another appropriate occasion for intervention. Addressing workplace safety, Somin writes that "workers should be allowed to decide for themselves whether they wish to accept increased risk in exchange for increased pay or benefits." But of course there are some risks, such as exposure to toxic chemicals, that workers will not even know about, and which therefore cannot influence the terms of employment.

Given constraints of time and space, I will not attempt a comprehensive response. But I will note that presumptions are an essential element of governance when case-by-case decision-making has severe systematic flaws - including those caused by political ignorance. Koppelman himself accepts such presumptions with respect to a wide range of (mostly non-economic) constitutional rights.

In addition, information asymmetries are a poor justification for government intervention when even larger asymmetries exist between largely ignorant voters on the one hand, and government regulators (and special interests that influence them) on the other. On the whole, workers have far stronger incentives to learn about the potential risks of their jobs than voters do to learn about the risks created by government policy. Introducing government regulation into the mix doesn't reduce information asymmetries. It increases them - often enormously so.

Finally, I'm not much moved by evidence that government officials concluded that their regulations passed cost-benefit analysis. I won't attempt a deep dive into the literature here. But analyses by economists outside government routinely paint a far different picture.

Show Comments (34)