Should Libertarians Root for the Abolition of Police and Prisons?

Libertarians have some common ground with the abolitionists—but if they insist on anti-capitalism as a litmus test, abolitionists will find themselves isolated and marginalized.

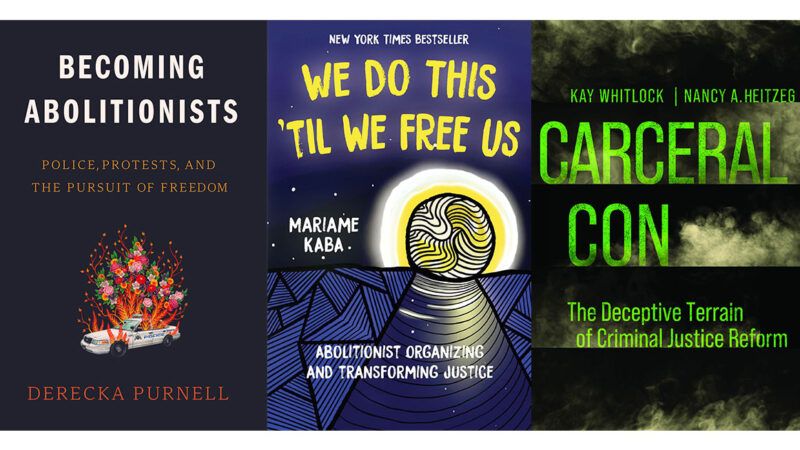

Carceral Con: The Deceptive Terrain of Criminal Justice Reform, by Kay Whitlock and Nancy A. Heitzeg, University of California Press, 280 pages, $22.95

We Do This 'Til We Free Us: Abolitionist Organizing and Transforming Justice, by Mariame Kaba, Haymarket Books, 240 pages, $16.95

Becoming Abolitionists: Police, Protests, and the Pursuit of Freedom, by Derecka Purnell, Astra House, 288 pages, $28

In Carceral Con, Kay Whitlock and Nancy A. Heitzeg reject "the popular but erroneous notion that the massive harms and injustices of the criminal legal system can be reformed as a standalone project."

Whitlock, an activist, and Heitzeg, a sociologist, are pushing back from the left against the "bipartisan consensus" on criminal justice reform: the general agreement among many moderate liberals and conservatives that the government should reduce sentences for nonviolent offenders and improve reentry services for people leaving prisons. Whitlock and Heitzeg contend that a network of well-funded nonprofit foundations and advocacy groups manufactured this consensus and that its proposed reforms will only further entrench the current system's injustices.

Carceral Con is the latest of several recent books advocating abolition of police and prisons. Abolitionist Mariame Kaba published a collection of essays, We Do This 'Til We Free Us, and Black Lives Matter activist Derecka Purnell released Becoming Abolitionists, a half-memoir, half-polemic about defunding the police. Although rising crime rates have taken the sheen off "defund the police" rhetoric since George Floyd's murder, it's worth examining these arguments free from the heat of recent political debates.

Part of Whitlock and Heitzeg's argument is uncontroversially true. During the last decade, foundations and advocacy groups have indeed pumped hundreds of millions of dollars into criminal justice platforms that were palatable enough to build bipartisan coalitions in Congress and statehouses. For liberals, there were talking points about the drug war's injustices; for conservatives, there were promises of cost savings from closing prisons and reducing sentences. It all stops well short of abolition.

Even radical libertarian thought traditionally has not had much to say about eliminating prisons. The anarcho-capitalist Murray Rothbard, in a 1973 essay arguing for abolishing courts' subpoena powers and compulsory jury service, still found prison an ideologically acceptable institution. "The libertarian believes that a criminal loses his rights to the extent that he has aggressed upon the rights of another, and therefore that it is permissible to incarcerate the convicted criminal and subject him to involuntary servitude to that degree," he wrote. In 1972, by contrast, Robert LeFevre rejected the entire concept of "retroactive justice" in the pages of Reason. "I do not think we need a government to do the one thing government has always taken as its exclusive domain—retaliation," LeFevre wrote. "It is, in fact, the urge for retaliation, the thirst for vengeance, that ties us to the state."

Libertarians have some common ground with the abolitionists. Abolitionists recognize, at least in their better moments, that every law is ultimately enforced at the end of a gun barrel. "Simply put, policing is violence, deployed by the state," Whitlock and Heitzeg write. But libertarianism and leftist abolitionism have never commingled much, because the leftist abolition movement is steeped in socialism and identity politics.

For Whitlock and Heitzeg, the historical strands of policing and incarceration in the U.S. all flow from what they call "racial capitalism." The general thrust of their argument will be familiar to anyone who followed the debate over The New York Times' contentious 1619 Project: Modern U.S. policing is an outgrowth of slave patrols and urban initiatives created to protect the accumulation of capital and to reinforce racial and economic hierarchies.

The criminal justice reform movement's "strange bedfellows" arrangement, which includes conservative organizations, evangelical groups, and business interests, is therefore unacceptable to Whitlock and Heitzeg. They see the bipartisan bonhomie as a smokescreen that obscures true abolition efforts and protects the carceral system. "The Right's preferred remedies for corporate/white-collar overcriminalization," they write, "are deregulation, evisceration of occupational licensing qualifications and safety standards, and getting rid of corporate and institutional criminal liability for even massive harms to individuals, communities, and entire geographies."

It is unclear how criminalizing interior designers and hair braiders for not being part of a professional cartel reduces state violence.

Since the specter of capital haunts all abolitionist analysis, true abolition requires nothing less than the complete dismantling of the current social order (minus occupational licensing, I suppose). "The occurrence of crime is inevitable in a society in which wealth is unequally distributed," the prominent black radical Angela Davis wrote in 1971.

Abolitionism, then, is only part of a radical transformation. "Our vision insists on the abolition of the prison-industrial complex as a critical pillar of the creation of a new society," Kaba writes. This program seems to have many pillars. For Purnell, abolitionism is "committed to decolonization, disability justice, Earth justice, and socialism." One's receptiveness to abolitionist rhetoric depends largely on one's acceptance of these leftist priors and the revolutionary endgame.

Setting aside the flawed core of leftist abolitionism—the claim that crime will be negligible in a society that eliminates material inequality—its advocates do offer some real insights. Whitlock, Heitzeg, and their fellow travelers are not wrong when they note that police and prison systems have been largely impervious to reform efforts. The history of American prisons is a cycle of reform and stagnation, starting with the first penitentiary in Pennsylvania and extending to the present day. Every 50 years or so, blue-ribbon committees and esteemed experts identify the same problems as their predecessors: overcrowding, filth, idleness, and brutality. "Reforms only make polite managers of inequality," Purnell writes.

Meanwhile, the rise of cellphones and body cameras has brought more visibility to policing, but it has not significantly changed officers' behavior. Derek Chauvin kept his knee on Floyd for nine and a half minutes despite being filmed from multiple angles.

It's also true that many of the reforms pushed by technocratic foundations and advocacy groups—such as specialty drug courts, mandatory "treatment," home confinement, and monitoring—do little to reduce the size of the carceral state, merely offering less sadistic methods of surveillance and control. And while red states like Texas, Georgia, and Mississippi liked to crow that they downsized their prison systems before the blue states did, the actual impact of those reforms is debatable. The bipartisan reforms that Mississippi passed in 2014 were projected to save the state hundreds of millions of dollars in prison spending. Spending did go down, as did the inmate population, but in 2019 the number of prisoners began to rise again. In the last two years, Mississippi's prison system has devolved into a full-blown crisis of inhumane conditions and horrific violence.

Abolitionists also are right to remind us that prisons were not always a fact of life. Imprisonment has existed since antiquity, of course. Ancient Thebes had the hnrt wr ("great prison"), while Athens had the desmoterion ("place of chains"). The Bible says Paul and Silas sang and prayed in shackles. Boethius wrote The Consolation of Philosophy in a cell. But until the development of the modern penitentiary in the late 18th century, such cells were mostly used to house debtors, heretics, and political malcontents. Criminals were typically banished, publicly tortured, or executed rather than incarcerated.

The abolitionist critique of reform is easier to accept on paper than in practice, however. I covered criminal justice reform efforts on Capitol Hill for years, and I found that many of the advocates who stalk the House and Senate office buildings and stand in sweltering midsummer rallies are themselves formerly incarcerated. I also interviewed people who were freed from life sentences because of the compromised, milquetoast reforms those activists pushed for more than a decade. While the newly liberated uniformly grieve for the friends they left behind in prison, there is little doubt for them—or for, say, the roughly 3,000 federal crack cocaine offenders released early because of the First Step Act—about whether small-ball reforms are worth pursuing.

Abolitionists are on firmer ground when they focus on developing alternatives to the criminal justice system, venturing beyond the narrow possibilities of state-approved reality. Purnell discusses violence disruptors and other interesting experiments in de-policing. Last year, Denver started sending mental health teams instead of police for certain calls. For years a similar program in Eugene, Oregon, called CAHOOTS, has responded to mental health emergencies. These small-scale experiments should be encouraged, studied, and improved. There is no reason, other than habit and entrenched political power, for police and prisons to hold a monopoly on how communities respond to crime, homelessness, drug addiction, and mental health crises.

Competition, as libertarians like to say, gives consumers better products. But if abolitionists insist on anti-capitalism as a litmus test, they will find themselves, as they were prior to Floyd's death and are yet again, isolated and marginalized in America's debates over policing and incarceration.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "Who Controls Criminal Justice Reform?."

Show Comments (110)